Revenge of the Perverted Patrolman

|

| Martin J. Sullivan |

Listen to the audio version here.

If you're a regular reader of the Pennsylvania Oddities blog, you've noticed that Western Pennsylvania has no shortage of mass murderers. There was Martha Grinder, the kind-hearted housewife who was hanged in 1865 for nursing her patients to an early grave. There was Charles Cawley, the teenage genius from Homestead who went berserk in 1902 and slaughtered his family with an axe... a tragedy replicated in 1939 by 17-year-old Beaver Falls High School student Paul Cook. But one of the most deranged killers in the history of Western Pennsylvania was neither a nurse nor an angry teenager, but a foppish 73-year-old policeman with a fondness for wearing wigs and makeup.

A thirty-one-year veteran of the Duquesne Police Department, Patrolman Martin J. Sullivan lived a quiet life at his home on Erwin Street. To the casual observer, Martin presented a non-threatening, if not downright comical, appearance: standing five feet and eight inches, the paunchy patrolman was by no means a physically imposing specimen. He was a vain man with a trunkload of insecurities, and he rarely allowed himself to be seen without his chestnut brown toupee, which was fastened to his head by way of a string tied under his double chin, and a thick coating of makeup which he believed concealed the lines and wrinkles of his no-longer-youthful face. What little hair remained on his head his dyed religiously; the mere sight of a gray hair filled him with panic. He was also rarely seen without his special "medicated cigarettes", which he smoked in order to ease the symptoms of his asthma.

Although Sullivan claimed to be 65 years old, his son, Martin Sullivan, Jr., told reporters that his father had been lying about his age for years. "He is 73 and was born in Ireland," declared the patrolman's son. "I know he says he was born in Lancaster and gives his age as 65, but I'm sure that's wrong." In reality, Sullivan was born in Galway on October 16, 1864.

A father of eight, Martin Sullivan was a grandfather to sixteen grandchildren. His wife, Phoebe, died in 1933, while one of his sons, Wolford, passed away the following year at the age of 36. Another son had died in infancy. Whatever impact these personal losses had on his mental health is unclear, but it soon became evident that Sullivan was a man who absolutely refused to grow old with dignity. He spent countless hours in front of his mirror in a sad attempt to turn back the hands of time, and as he grew older his collection of makeup only grew larger. His assortment of lipstick, rouge and eyebrow pencils rivaled that of women half his age. Meanwhile, his sexual appetite grew more and more insatiable, while the objects of his affection became younger. For this reason, his grandchildren weren't permitted to visit him very often, and when they did, they were kept under the strictest of supervision, as their parents strongly suspected that something was a little "off" about Grandpa. And they were correct.

In December of 1936, Martin Sullivan was accused of sexually assaulting Antoinette Vukelja, a twelve-year-old girl who lived a short distance from his home in Duquesne. It was the girl's mother, Mary Vukelja, who became suspicious after Sullivan bought the girl a pair of shoes and a wrist watch. She had also been warned to keep her children away from the Sullivan home by a neighbor named Helen Benda, whose teenage daughter (also named Helen) had been employed by the patrolman as a housekeeper-- until he fell in love with her and asked her parents for her hand in marriage. The Bendas refused, of course, as Martin Sullivan was nearly fifty years her senior.

Upon learning that Sullivan had developed a neighborhood reputation for acting inappropriately towards children, Mrs. Vukelja discussed the matter with a social worker named Laura Klawson Bacon, who lived a few blocks away. Mrs. Bacon investigated these rumors, and, after speaking with Antoinette, told the girl's mother the terrible truth. Her worst fears confirmed, Mary Vujelka went to the authorities. After swearing out a complaint before Alderman C. Dewain King, Sullivan was arrested by Constable Thomas L. Gallagher, an old friend of more than thirty years, and taken to King's office for a hearing. At six o'clock on the evening of December 17, he entered a plea of not guilty.

Tour of Death

Shortly before eight o'clock that evening, after hearing testimony from Mary Vukelja and Laura Bacon, Alderman King ordered Sullivan to be held without bail to await trial on a charge of rape. The pudgy patrolman was remanded into the custody of Constable Gallagher and they started on foot for the Duquesne lockup, where the prisoner was to be held until morning, when he would be transferred to the county jail. Along the way, Sullivan asked Gallagher if he could stop to speak with his son in order to tell him to lock up his house on Erwin Street.

Constable Gallagher didn't see any problem with this, and the prisoner was permitted to go inside his son's house at the corner of Second Street and Priscilla Avenue. However, while the constable waited outside, Sullivan promptly ducked out the back door and raced back to his home, eight blocks away, where he fetched his police revolver and sixteen extra shells. Then he went to the Benda home, which was located two blocks away at No. 10 Erwin Street. He quietly entered the building and climbed the stairs to the second floor apartment. He opened the door to the apartment and helped himself to a drink of water in the kitchen. Just then, Joseph Benda came into the room and Sullivan asked to see his wife, Helen. When Helen entered the kitchen, Sullivan began shooting. She fell atop her husband, who was already dead. Helen would die two hours later at McKeesport Hospital.

"We heard two shots and saw Dad slump on the floor face down," recalled Julius Benda, who, along with his brother John, witnessed the murder of his parents. "We both ran into the bedroom, thinking Sullivan was coming after us. Then we ran into the kitchen and down the street, hollering."

|

| Doctors fight to save Helen Benda's life |

Martin Sullivan left the apartment and hurried down Parallel Alley. After three blocks he turned onto McRae Street and soon arrived at the Vukelja home. Inside the home at 14 McRae Street he found Mary Vukelja, her husband Joseph, their two sons Milan and Walter, and the twelve-year-old child he had allegedly assaulted. There an awkward moment of silence after Sullivan stormed into the house, but the silence was shattered by gunshots. Mary Vukelja ran upstairs as her wounded husband stumbled into the basement. Their 23-year-old son, Milan, attempted to shield his family with his body-- a heroic act which proved fatal. After shooting Milan, Sullivan dashed up the stairs, knocking down two doors Mary had locked behind her. She attempted to escape by climbing out the window onto the roof of the porch. Sullivan watched her jump to the ground. He rushed back downstairs and out of the house, where he found her screaming for the police.

"You want the police?" sneered Sullivan, pointing his revolver at the frightened woman. "Here's the police!" He fired a shot into her head at close range, and another into her stomach as she lay on the ground.

A neighbor, Mrs. Malik, attracted by the gunshots, ran into the Vukelja home with little regard for her own safety. She found Milan's lifeless body on the living room floor. Thirteen-year-old Walter, who had ran into the basement to hide, escaped undetected and ran to a nearby store, where he called police. The daughter, Antoinette, was sobbing. Mrs. Malik took the girl by the hand and led her across the alley to the home of Frank Wagner. Unfortunately, this decision nearly cost them their lives, as they walked directly into Sullivan's line of fire. Bullets whistled overhead, with one of them crashing through the back door of the Wagner home, missing the unsuspecting owner by inches. Antoinette Vukelja and Mrs. Malik were able to escape without a scratch. The shooter retraced his route and returned to a waiting Constable Gallagher, who was oblivious to the massacre his "prisoner" had just carried out. But Martin Sullivan's revenge plot wasn't over quite yet.

|

| The Vukelja home and Antoinette Vukelja |

Stops for a Drink, Adds Another Victim

Next, Sullivan asked the constable if they could stop for a drink. They went to a nearby saloon, where Sullivan ordered a whiskey and the constable had a beer. Sullivan then suggested that Constable Gallagher accompany him to the home of Laura Clawson Bacon, the social worker. Gallagher asked why he wished to see Mrs. Bacon. "I want to thank her for something she done for me," replied Sullivan. The clueless constable consented, and together they went to the Bacon residence at 229 South Second Street. Sullivan knocked on the door and was let inside by Laura's son-in-law, Howard Wiesen. Laura, who was sitting in a chair in the parlor, agreed to speak with Sullivan, and, after their brief conversation, Sullivan pulled out his revolver and shot her, killing her with a single bullet. The awestruck constable grabbed him by the arm.

"Martin, are you crazy?" he said.

"Don't worry. I won't shoot you, pal," replied Sullivan. "That's all the shooting for today. Let's go down to the station."

Sullivan and Gallagher resumed their walk to the Duquesne police station. By the time they arrived, District Attorney Andrew T. Park and Chief County Detective Peter Connors were already waiting.

|

| A younger Sullivan in uniform; The killer's route |

Sullivan's Confession

In the presence of District Attorney Park and County Detective Connors, Martin Sullivan leaned back in his chair and freely confessed to five murders, though he said that some of the victims had been shot simply for getting in the way. However, he lamented the fact that he had failed to kill Walter Vukelja, who had testified against him at the hearing before Alderman King. According to Martin Sullivan, the motive was strictly revenge-- on the Vukeljas because they had charged him with molesting their ten-year-old daughter, on the Benda family because it was Mrs. Benda who had informed Mrs. Vukelja that Sullivan was molesting Antoinette, and on Mrs. Bacon for being the one who had advised them to press charges. When asked if he had any remorse, the police veteran of thirty-one years smirked.

"I'm glad I did it," said Sullivan. "I'd do it again. I'm satisfied, even if I did miss one person. If I had gotten him, I'd have made a clean sweep. I wanted revenge, and I got it. I know I'm going to the electric chair, but I'm not sorry." Detectives and other witnesses to the confession were so taken aback that they could only stare at the man in the chestnut toupee. Sullivan found the silence unnerving. "What's the matter with you?" he demanded. "You look at me as if I was insane!"

Wondering if the prisoner had perhaps drank more than just the single whiskey he had claimed, detectives had a physician, Dr. Daniel Sable, examine him. Sullivan was pronounced sober.

|

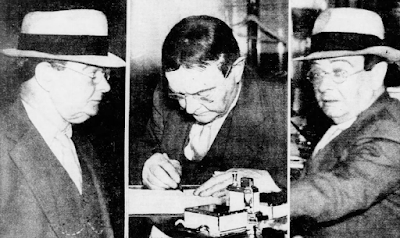

| Sullivan at his confession |

"The man claimed that he was being framed and felt that people were persecuting him, so he decided to square accounts," stated District Attorney Park. "He wanted revenge on Mrs. Vukelja for prosecuting him on charges which he claimed were false. He claimed that Mrs. Benda had told Mrs. Vukelja of relations between him and the little girl. Sullivan claims these stories are untrue. The parents of Antionette had consulted with Mrs. Bacon, the social worker, and had taken her advice about what action should be taken against Sullivan. For that reason he was angry at Mrs. Bacon."

However, authorities believed there was something fishy about the whole thing. For perhaps the first time in recorded history, a prisoner had managed to murder five people while in the custody of the arresting officer. In less than sixty minutes, Sullivan was able to run uphill for eight blocks to his home, up and down several flights of stairs, fire off seventeen rounds and snuff out the lives of all but one of the individuals on his revenge list at three separate locations-- while still having enough time left over to sit down at a bar for a drink of whiskey. This would've been an impressive performance for someone young and athletic. Yet it was carried out, under the very nose of Constable Gallagher, by a portly and unathletic 73-year-old grandfather with asthma.

|

| Sullivan on his way to sign the confession. The string he used to attach his toupee is visible under his chin. |

Was Constable Gallagher really as clueless and inept as it seemed? Or did the constable simply turn a blind eye to the bloodbath because Martin Sullivan was a lifelong friend? After securing Sullivan's confession, District Attorney Park and Chief County Detective Connors ordered the arrest of Constable Gallagher for malfeasance on duty and allowing a prisoner to escape.

"I had known Martin Sullivan for thirty years," the constable later explained. "I saw him every day around town or at the police station and never knew him to be anything but a quiet fellow, so I didn't handcuff him."

A Community in Mourning

With Christmas just one week away, the residents of Duquesne grappled to come to terms with the tragedy which rocked their close-knit community. Hundreds of neighbors tried their best to comfort the Benda, Vukelja and Bacon families, which would forever associate the holiday season with the cold-blooded murders of their loved ones. Joseph Benda, Jr., traveled to the morgue on the evening of the murders to view the bodies of his parents one final time. Accompanied by his wife, the eldest son of the Benda family clung to the wooden banister of the morgue stairs, alternately sobbing with grief and fuming with rage.

"If only I could get my hands on Martin Sullivan," he said to reporters gathered at the morgue. "Why, only this morning I waved to him on my way to work at seven o'clock! He was directing traffic at Duquesne Street." According to Joseph, whose sister had worked for Sullivan for three years, the patrolman was always inviting young children into his house, giving them candy and money. Though he was aware of the terrible rumors and the tension between Sullivan and the Vukeljas, he never expected the drama to unfold the way that it did. And never in a million years did he think that his own family would become the target of the patrolman's wrath.

"I didn't even get home before I heard the awful news," continued Joseph. "I had to pass the police station and I saw a big crowd of people there, so I stopped to see what was the matter. They told me Sullivan had killed my mother and father. If I could have gotten my hands on him, I would have killed him, too.

"Just ask District Attorney Park if he's looking for somebody to pull the switch on the electric chair. I'd do it on a moment's notice. You ask how I feel about Sullivan? Why, I'd strap him in the chair personally, and beg for the opportunity."

|

| The Vukelja home on McRae Street. The "X" marks the spot where Mary was gunned down by Sullivan. |

Meanwhile, Antoinette returned to the Vukelja home on McRae Street, where she was looked after by her nineteen-year-old sister Rose and seventeen-year-old brother Jack. Preparations for the funeral were already taking place. Despite the savagery of the previous day, the neat little home reflected the loving care that the murdered mother had given it. Curtains as white as snow hung in the windows, the polished faucets of the kitchen sink gleamed. The parlor had been cleared of furniture in anticipation of the caskets bearing the bodies of Mary Vukelja and her son, Milan. The city of Duquesne had a large Croatian population, and friends of the family continually dropped in to check on the children, especially the dark-haired little girl who had spilled Martin Sullivan's dirtiest secrets.

Asked by reporters how she had met Martin Sullivan, Antoinette began to cry. "I used to go to his house with the Benda girl who worked there," she said. "That's how I met him." Her older sister, Rose, told the girl to keep quiet.

"Don't you talk any more," said Rose. "Isn't it a bad enough disgrace to our home already about those charges mother had to make against that man? Keep quiet."

Sorrow also reigned at the home of Laura Clawson Bacon, the beloved social worker. The South Second Street home was filled with floral arrangements paying tribute to the widow who had single-handedly raised five children before turning her attention to helping others in need. Sadly, her son, Emory Bacon, was to be married on December 19 to his high school sweetheart, Helen Hotham. But instead of smiling guests bearing gifts for the bride and bridegroom, a steady stream of mourners came to pay their final respects before Mrs. Bacon's body was transported back to her native Cincinnati for burial. Later, it would be revealed that her estate, which was divided among her five children, was valued at just $1,472 at the time of her death.

|

| Laura Bacon |

Rumors of Other Abuse Victims

Even the killer's own family admitted that Martin Sullivan's behavior with children made them uncomfortable. His daughter-in-law said that Martin hadn't been inside their home for over two years. "He never came around because he knew we didn't like him having the girls in his house," she said. The killer's son agreed.

"We often had arguments about that," admitted Martin Sullivan, Jr. "We didn't like it and we had words with him from time to time. I can't understand my father. He was always good to us. I just can't understand. I can't. It's a hard thing for us children to live down."

When asked about other possible victims of sexual abuse, Alderman C. Dewain King admitted that he had learned of several during his closed-door conference with Mrs. Bacon, though he refused to provide further details.

The Man Under the Wig

District Attorney Park made it clear that his goal was to see Martin Sullivan pay for his crimes in the electric chair. His only concern was that a lunacy commission might declare the Duquesne patrolman insane. To prevent this for happening, Park appointed two psychiatrists, Dr. Edward Mayer and Dr. C.H. Henninger, to conduct a painstaking physical and psychological examination of Sullivan.

On Monday, December 21, Martin Sullivan came out from under his wig. The smirking killer was stripped of his vanity and forced to leave behind his toupee when county detectives confiscated his lipstick, rouge and eyebrow pencil and removed him from his cell at the Allegheny County jail to be taken to the courthouse for mugshots and fingerprinting. Photographers crowded around for the moment detectives raised the hat covering his hairless scalp. Sullivan was furious. "What are you taking a picture of my bald head for?" he demanded, trembling violently. He was even angrier when he was forced to remove his false teeth. During fingerprinting, his hands were shaking so much that they had to be held down.

Sullivan's outburst and nervous condition were noted by Detective Connors, who wondered if the killer's conceit was false bravado-- perhaps the defense mechanism of sick and deeply insecure man. As it seemed that Sullivan was actually looking forward to his inevitable execution-- he'd told detectives repeatedly that the sooner he gets the chair, the better-- Connors considered putting the prisoner on suicide watch as a precaution. "I'm afraid he's liable to bump himself off," said Connors.

|

| Sullivan without his toupee and makeup |

The Inquest and Indictment

Coroner McGregor held the inquest on December 29, with seven witnesses called to testify behind locked doors. Fifteen police officers were assigned to guard Sullivan out of concern for vengeance. The prisoner stared at the ground as witnesses recounted their brush with death, with Mrs. Bacon's son-in-law declaring, "If I'd had a gun that night it would've saved the county a lot of money." Martin Sullivan grinned when the verdict was read, ordering him to be held for the grand jury. On January 5, 1937, the grand jury handed down five murder indictments against Sullivan. His trial for the murder of Laura Clawson Bacon was set for January 18, with Judge J. Frank Graff presiding. Although Sullivan insisted upon not having legal counsel, Judge Michael A. Musmanno appointed a veteran criminal defense attorney, Edward Coll, to defend him. It was reported that Coll intended to prove that the defendant was insane at the time of the murders.

Meanwhile, Constable Thomas Gallagher was facing his own legal troubles. On January 7, he waived his right to a preliminary hearing and was released by Alderman Andrew Maloney on a $20,000 bond. Gallagher, who would not be tried until after Sullivan's case was disposed, faced up to 11 years in prison if convicted on charges of malfeasance in office and permitting the escape of a prisoner.

|

| Constable Thomas Gallagher |

The Mystery of the Missing Hairpiece

Late on the evening of January 16-- just eleven hours before the trial was scheduled to begin-- District Attorney Park made a surprise announcement, stating that he no longer intended to prosecute the case himself, as he planned to testify as a witness. Instead, the prosecution would be led by the young, but capable, assistant district attorney, Chauncey Pruger. Park also announced that the murder trial of Martin J. Sullivan would be postponed, as his hand-picked psychiatrists needed more time to observe the killer. This incensed defense attorney Edward Coll. "He (Park) has been insisting on going to trial and only gave me a week to get ready," said Coll. "I have made all my arrangements and I object to a postponement." Coll asked the court to proceed with the trial as planned. Judge Masmanno, however, sided with the district attorney taking the rare step of personally interviewing Sullivan in his jail cell.

This was a welcome bit of news for Sullivan, as the month-long postponement gave him more time to track down his toupee, which had gone missing after it was taken from him during his trip to the courthouse for fingerprinting. Jail officials claim that Sullivan had been wearing it when he left the jail to go to the County Detective Bureau at the courthouse, while detectives claimed they were unable to locate it. Because of the sensational nature of the case, many believed the toupee had been stolen by a corrupt Allegheny County detective (of which there were many) and sold to a relic hunter, though this has never been proven.

|

| Judge Graff (pointing, left picture) leads tour of crime scene. The Vukelja home (right). |

Them Bad Things

On the morning of May 17, the indictment was read by court clerk John Shenkel and the defendant appeared visibly nervous without the security of his hairpiece. When the clerk asked the defendant to enter his plea, Sullivan whimpered before falling silent. "The prisoner stands mute," said Judge Graff. "The court will enter a plea of not guilty for him."

Next came the jury selection, followed by a tour of the crime scene on May 18 led by Judge Graff. Jurors were permitted inside the Benda, Bacon and Vukelja homes for a close inspection, while Sullivan, under heavy guard, stood outside and faced the jeers and catcalls of local citizens. On May 19, Constable Gallagher and Antoinette Vukelja were called to testify. The jury leaned forward as the 12-year-old girl spoke in barely audible whispers in response to Assistant District Attorney Pruger's questions.

"Helen told me all about those things he does and everything-- them bad things," she said, referring to Sullivan's teen-aged former housekeeper.

"You say you went down to Sullivan's house five times?" asked the prosecutor. "And he did those things to you and other little girls?"

"Yes," whispered Antoinette. After a cross-examination by defense attorney Coll, the girl stumbled from the witness chair, sobbing, and raced into the arms of a relative.

|

| Mary Vukelja and her husband, Joseph. |

The next witness was Joseph Vukelja, the father who was still recovering from the gunshot wound he received five months earlier. He slumped in the witness chair as he retold the story of the death of his wife through an interpreter. Tears streamed downs his face as the Croatian millworker spoke. Then he lifted his shirt and bared his right hip to show the jury the angry purple scar. Vukelja became even more emotional when he spoke of Milan, whom he watched helplessly as the young man gasped his last breath. While Joseph Vukelja put his head in his hands and cried, Martin Sullivan grinned at the floor, chuckling as he fidgeted with his tie. Noticing this behavior, the jury gasped and grumbled.

"No cross examination," said Edward Coll after Vukelja finished his emotional testimony.

The defense presented its case on May 20. Attorney Coll's first witness was Duquesne chief of police Thomas Flynn, who testified that Sullivan was a very good patrolman. But things went seriously awry for the defense when attorney Coll asked about Sullivan's reputation.

"Well, I had complaints against him for five years back," answered Chief Flynn.

"I didn't ask you that!" roared the defense attorney, who tried, but failed, to have Flynn's response stricken from the record. On cross examination, Assistant District Attorney Pruger pounced on the opportunity to put the proverbial nail in the coffin of the defense. He asked Flynn to tell the court what the complaints against Sullivan were.

"That he was fooling around with little girls on his beat," replied Chief Flynn.

|

| Chief of Police Flynn examining the murder weapon |

The Killer's Daughter Testifies

One of the more interesting witnesses was Mrs. Frances Sweeney, a 43-year-old daughter of Martin Sullivan. Her testimony provided a fascinating glimpse of the man behind the makeup. According to Mrs. Sweeney, her father had become an entirely different person after the death of his wife in 1933, when 45 years of marriage came to an unexpected end. Only then did her father begin wearing lipstick and rouge in a sad attempt to stop time in its tracks. Mrs. Sweeney's testimony paved the way for Coll's star witnesses, psychiatrists Dr. John Frederick and Dr. Theo Diller.

Dr. Frederick claimed that Martin Sullivan didn't know his own age, his own birthplace, the number of children he had or their names. According to Dr. Frederick, the killer had told him that, after his hearing at Alderman King's office, his "eyes went black and his head whirled." The psychiatrist also told the court that Sullivan had been suffering hallucinations while locked up in jail. "He spoke of airplanes trying to get him at night and was bothered by voices until he asked for a sleeping potion," stated Dr. Frederick. This corroborated the testimony of one of the prosecution's witnesses, Dr. Edward Mayer, who said under cross-examination that Sullivan had told him "something picked him up by the neck and took him to McKeesport, then returned him back to jail."

|

| Three of Sullivan's daughters. From left: Elizabeth Shaffer, Frances Sweeney, and Hazel Rife. |

Nonetheless, Dr. Mayer insisted that Sullivan was merely suffering from a run-of-the-mill case of prison psychosis. "I cannot find anything that would convince me that Sullivan was mentally deficient at the time of the shootings," declared Dr. Mayer. "I would say that he was perfectly sane."

To nobody's surprise, the jury of nine women and three men found Martin J. Sullivan guilty of murder in the first degree on the morning of May 22, 1937, and recommended a sentence of death by electrocution. Though Sullivan appeared calm and collected, Court Crier John Englert, with a hand supporting the veteran patrolman he had known for 55 years, felt a tremor shake the body of the elderly, bald-headed killer. "Buck up, Marty," whispered Englert. "There's lots more to come."

"I don't give a damn," replied Sullivan. "I'm an old man now. I don't care. It's just that this verdict is a disgrace to my family. I don't care except for that."

Terrified by Traffic

In December, Governor George H. Earle fixed the date of February 14, 1937, for the execution. Sullivan's attorney, Edward Coll, said that his client had no interested in appealing the conviction or asking the Board of Pardons for a commutation to life imprisonment. The execution date was later pushed back to February 28, and then again to March 21. These delays had a deleterious effect on the prisoner and he eventually showed signs that he was beginning to crack. Prison guards reported hearing "weird cries" coming from Sullivan's cell at night, and the condemned man claimed to be tormented by the ghosts of his victims.

On February 27, Sullivan was transported from the Allegheny County Jail to the death house at Rockview Penitentiary in Bellefonte. One of his traveling companions during the 165-mile trip was Pittsburgh Post-Gazette staff writer Harry Kodinsky, who observed that Sullivan was no longer the sneering, red-cheeked patrolman he had encountered the day of his arrest, but a "pale, glassy-eyed and quivering" man who "screamed in fright one moment and joked about impending death the next".

Sullivan had begun screaming in a shrill, nasally voice soon after the car pulled onto Fifth Avenue. As it turned out, the former traffic cop was frightened by the traffic.

"Each time an automobile or truck with bright lights would fly by, he would cry out and throw his hand into the air," said the reporter. "Everyone in the car was terrified."

Sullivan emitted another ear-piecing scream when he saw a black cat, but his outbursts ceased after the lights of the city were far behind. During the journey, he bounced back and forth between excitedly re-enacting his murders and reliving his boyhood in Ireland.

"I'm not afraid to die," he said to Kodinsky at one point, as the sheriff's automobile slid along the icy mountain roads, "but wouldn't it be funny if we had an accident?"

|

| Sullivan smiles as jurors view the crime scene in horror during Judge Graff's tour. |

Dreamed of Being a Musician

During the ride to Rockview, Sullivan revealed that his one unfulfilled dream in life was to be a clarinet player in a symphony orchestra. "I was born in Ireland. County Galway. I studied in school there until I was 15 years old and came here," reminisced the killer. "In those schools there you learn things. My mother and father were here when I came over. You know, my father lived to be 98 years old. My mother was 87 when she died in McKeesport Hospital.

"In school I played the clarinet," he continued. "I wanted to go on playing like some friends I have who are now in the Pittsburgh Symphony. I played for Charlie Schwab, the steel man, several times. I was at his home a couple of times. Beautiful home. He played the piano and I played the clarinet." It was Charles Schwab who offered Sullivan a job at a steel mill in Braddock. "It was the first job I ever had. I used to straighten rails." Later, he worked for the Duquesne Steel Works. In 1901 he joined the Duquesne Police Department.

Sullivan's mood changed, however, when the conversation turned to Antoinette Vukelja and Laura Clawson Bacon. "They were all in on the framing. They were all telling lies. A man's got to protect his character... I can't blame the little girl. They forced her to tell lies to frame me." As the car approached Rockview Penitentiary, the prisoner chuckled. "So this is the Big House, huh? It's a little place, isn't it?"

|

| Sullivan en route to Rockview Penitentiary |

Execution Day

As the date of the execution drew near, all eyes turned to Bellefonte to see whether or not the smirking ex-patrolman would face the electric chair with bravado. He appeared calm on Saturday, March 19, when Deputy Warden C.C. Rhoades read him the formal notice of execution. He made no last requests, and he ate the regular prison fare as his last meal-- rice soup, cheese, cake and coffee. Sullivan's only statement was to Dr. J. Claudy, superintendent of Rockview Penitentiary. "I've never been in better condition to die," he told the superintendent just before two guards fetched him from his cell at a little past midnight on the morning of March 21. He shuffled casually to the electric chair, except for an instant when he stumbled as he caught his first glimpse of the instrument of death known as "Old Sparky".

Martin Sullivan settled onto the oak seat and clutched the arms of the chair. As the executioner, Robert G. Elliott, lowered the mask over his face, Sullivan muttered, "You're smothering me." Those would prove to be his last words; at 12:25, after Executioner Elliott strapped the heavy leather belt around Sullivan's chest and fastened the electrode to his left leg, his hand moved quickly to the switch. The lights in the prison dimmed for a moment and loud humming noise filled the air of the death chamber as 12,000 volts coursed through the killer's body.

Suddenly, Robert Elliott turned around to review his work. The prisoner was heavier than he had initially thought; more current was needed. Soon, wisps of blue-gray smoke began to pour out from behind the mask and from the legs of Sullivan's trousers, swirling upward to the ceiling. Elliot worked the rheostat like a virtuoso, turning the dial back and forth to prevent the body from blistering and burning. "Heating and cooling" was the term he had given this morbid maneuver. He continued to deliver the current until Sullivan's skin was a deep red and then whirled a wheel on the control board. The lights inside the prison glowed brightly again.

Dr. W.J. Schwartz walked over to the chair with his stethoscope as twelve witnesses held their breaths. Only the ticking of the prison clock could be heard over the silence. It was thirty-five minutes past midnight. The doctor straightened and faced the witnesses. "Gentlemen, I pronounce Martin Sullivan dead."

Having celebrated a birthday while in prison, Martin Sullivan was 74 years of age at the time of his death, making him the oldest person ever executed in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. After the execution, Sullivan's body was taken to the Campbell Funeral Home in Sharpsburg and buried the following day at St. Joseph's cemetery (Row O, Section I) in Mifflin Township, in a plot just a few paces from four of his five victims.

As for Constable Thomas L. Gallagher, whose prisoner committed five murders while in his custody, he was let off the hook with a slap on the wrist. His trial, which had been set for December 5, 1938, was postponed until February, 1939. By then, a petition calling for leniency had garnered over 2,000 signatures, mostly from fellow Allegheny County law enforcement officials and members of political and fraternal organizations. The petition was presented to Judge J. Frank Graff, who sentenced Gallagher to two years of probation.

BONUS: Additional photos of the killer, victims and key figures in the Sullivan case appear below.

|

| Mary Vukelja (left) and Laura Clawson Bacon |

|

| Sullivan's confession |

|

| Antoinette Vukelja |

|

| Joseph Vukelja, Sr. being treated at hospital. |

|

| Jury tours crime scene. On right photo, prosecutor Chauncey Pruger and District Attorney Park discuss the case with Edward Coll and Judge Graff. |

|

| Mourners gather around the caskets of Mary Vukelja and her son, Milan. |

|

| Walter Vukelja, who escaped death by hiding. |

Sources:

Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph, Dec. 18, 1936.

Pittsburgh Press, Dec. 18, 1936.

Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Dec. 19, 1936.

Pittsburgh Press, Dec. 19, 1936.

Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph, Dec. 20, 1936.

Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Dec. 22, 1936.

Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Jan. 8, 1937.

Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Jan. 9, 1937.

Pittsburgh Press, Jan. 17, 1937.

Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Jan. 18, 1937.

Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph, May 6, 1937.

Pittsburgh Press, May 18, 1937.

Pittsburgh Press, May 19, 1937.

Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph, May 19, 1937.

Pittsburgh Press, May 20, 1937.

Pittsburgh Press, May 21, 1937.

Pittsburgh Press, May 22, 1937.

Pittsburgh Press, Feb. 14, 1938.

Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Feb. 28, 1938.

Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph, March 21, 1938.

Pittsburgh Press, March 21, 1938.

Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph, March 22, 1938.

Pittsburgh Press, Feb. 23, 1939.

Comments

Post a Comment