The Brutal Murder of Mary Quinn

The blood-chilling murder of a young Scranton woman named Mary Quinn remained unsolved for twelve years, until an epidemic of rape and physical attacks on young women in nearby Wilkes-Barre finally led police to her killer. This is the tragic tale of the crime; it is a story of unimaginable violence, heartbreak and the relentless pursuit of justice. And considering that Quinn's slayer received a surprisingly lenient sentence-- and went on to rape again after his release from prison-- it is also a tale of imperfect justice.

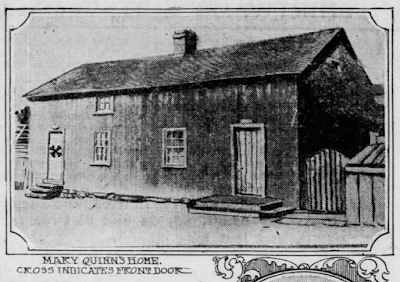

Mary Quinn was a silent, unassuming young woman who was well liked throughout the neighborhood where she lived, in what is now part of West Scranton. At the turn of the century this sparsely populated region was known as Keyser Valley, and the Quinn family-- comprised of Mary, her sister and a brother-- lived in a mining "company house" on the edge of a field known as Continental Commons.

On the night of June 2, 1902, Mary was alone in the house baking bread when she realized that she was out of yeast. With the stars to light her path she made the decision to cross a field and procure some yeast from a neighborhood store. It was a little after 9 o'clock when she left her house and walked down the lane, stopping to talk with a number of friends and neighbors along the way. Near the Hyde Park shaft she visited the home of a friend, Mary Herrick, but by the time she had left her friend's house it was after 10 o'clock, and she realized that it was too late to continue her journey for yeast. She started for home, encountering two policemen near the railroad crossing who warned her that it was not safe for a girl to go unprotected in that part of the valley late at night.

Mary told the officers that she would be fine. After all, she had been born and raised in the vicinity, and she knew every man, woman and child in the neighborhood. As far as she knew, she didn't have an enemy in the world, and certainly none in Keyser Valley. The policemen sighed and Mary Quinn continued her journey home, choosing to take the policemen's advice to stick to the main road instead of cutting across Continental Commons, as the field was known in those days. This fateful decision was one that would cost her her life.

Not far down the road she was attacked by a dark figure that leaped from out of the shadows. Mary never had a chance to scream for help; the assailant struck her in the back of the head with a wooden club without warning. With a pool of blood forming on the road around her limp body, the attacker ripped off her clothing. He wasn't sure if the girl was alive or dead, but it made no difference-- he raped her anyway, stopping only to drag her body off the road and into a field when he thought he heard someone approaching.

Daylight revealed the attacker's depravity and illuminated the unthinkable brutality of the crime. A trail of blood extended from the spot on the road where she had fallen, over a wooden fence, and into the pasture where her body was found later that evening. Mary's hair comb was found in the road, and a clump of her hair on the fence. Investigators surmised that she had regained consciousness at some point; for some horrible reason the attacker returned to the road where he had dropped his club and came back to the girl and bashed in her forehead, crushing the skull to shards just above the left eye.

"The force of the blow was so severe that the girl's skull was crushed into a pulp, and not a whole bone remained... the brain matter was exposed. This silenced her for all time, and the murderer left her for dead and made good his escape."-- Philadelphia Inquirer, June 15, 1902.

Before making his escape, the attacker threw his weapon into the bushes, where it was found the following day, covered in blood and hair. Mary's yeast bottle, which she had been carrying with her at the time of the brutal assault, was located nearby.

Astonishingly, Mary was still clinging to life when her body was discovered shortly before midnight by John Lukas and Joseph Frudowsky, two men who were returning home after their shift in the mines. They had heard a strange moaning sound coming from Continental Commons, and went to investigate. When they struck a match and saw the bloody body, they ran as fast as they could to the first house they saw-- which happened to be the home of the Quinns. It was Mary's bother, John, who opened the door.

"We've found a woman who is half murdered!" gasped Lukas. John summoned a few neighbors-- Thomas Sweitzer, Patrick Scott and Frank Moran-- and the party raced to the spot where the body lay. It was Quinn who lit the match and held it to the woman's face. He collapsed when he discovered that he was staring into the face of his own sister. The other men called for a doctor, J.J. Brennan, who raced to the scene, but Brennan declared that nothing in the world could be done for the dying girl. They put her body on a makeshift stretcher and carried her to the Quinn house. If nothing else, at least Mary would be able to pass away in her own home, surrounded by those who loved her.

Outrage in the Electric City

The rape and murder of young Mary Quinn outraged the entire city, and every member of the police force put aside other pursuits in order to focus on catching the cowardly killer. Meanwhile, the county commissioners put up a large reward for information leading to the arrest of the perpetrator. They released the following notice:

"Notice is hereby given that the county of Lackawanna will pay the sum of five hundred dollars reward to the person or persons securing the arrest and conviction of the party or parties responsible for the death of Mary Quinn, who was supposed to have been murdered on the night of the 2d of June, 1902, in Keyser Valley, Scranton, Pa. Signed, John J. Durkin, John Penman, J. Courier Morris, commissioners; E.A. Jones, County Controller."

Police eventually focused their efforts on one individual, a black man by the name of William Perry, who had a criminal history of molesting young women after knocking them unconscious with a wooden wagon tongue wrapped in fabric from a pair of stockings. Although the modus operandi was similar, Perry had a rock-solid alibi and was never charged in connection to Mary Quinn's death.

Just one month after Mary's death, her brother John died at the age of thirty after a long illness attributed to mental illness brought on by the death of her sister. His was the fourth death to ravage the Quinn family that year. The mother passed away first, followed by John's twin brother, and then Mary. Only a sister, Anna, remained.

The year is now 1914, and the Keyser Valley of Mary Quinn's youth is hardly recognizable. The booming coal business has ushered in waves of new arrivals to Lackawanna County, and the fields of Keyser Valley have all but disappeared, replaced by rows and rows of coal company housing. Census records show that the population of Lackwanna County nearly doubled between the time that Mary Quinn was born to the time that the first breakthrough in solving the case came in 1914.

To put this span of time into perspective, two weeks after Mary was killed, a rowdy and incorrigible seven-year-old boy named George was enrolled at St. Mary's Industrial School for Boys in Baltimore. Nineteen days before Mary Quinn's killer was finally identified, that same boy was making his first appearance as a professional baseball pitcher for the minor-league Baltimore Orioles. That boy, of course, was George Herman "Babe" Ruth.

Confessions of a Predator

In March of 1914, several young girls were molested in Wilkes-Barre in the vicinity of Grove Street. Descriptions of the attacker given by victims led to the arrest of William Pegram, described by newspapers as a "colored degenerate" with a "failing for white women". The 42-year-old Pegram, who was picked up by Sergeant Adam Hergert on March 26 in connection with an attack on a 13-year-old girl from Farley Lane, surprised authorities by confessing to the 1902 murder of Mary Quinn. The admission was so stunning that Chief of Police John Roberts warned Pegram against making statements about the deceased girl, as those statements could be used against him.

Pegram, however, either failed to grasp the seriousness of what he was about to do, or simply did not care. He spoke freely about the murder and was subsequently asked by Chief Roberts to write a full confession, which he did. Pegram wrote:

"I was living in Raymond's Court, Scranton, with my sister (Ida Pegram), who kept house for a man named Andrews. I got acquainted with Miss Mary Quinn. I first met her in Hyde Park near the green houses. I went to Hyde Park often and other places around the city of Scranton looking for women. During the month I lived there I did not work. Other times I worked at the Vulcan Iron Works in Wilkes-Barre and went up to Scranton often.

"I chased a woman in West Scranton one night. I met her at the turn off by the green houses near a cemetery. I went to have some fun, to fool with her. I met her outside. I went to the prop yard of a mine near her house and got a cart hook or some other club. I hit her in a field and when she fell down I dragged her away behind the bushes. Then I went down the steam railroad track to Cannon Ball Depot. I kept out of the way as I did not know whether anybody was watching me or not."

Pegram claimed that, in the years following the murder, he kept a low profile by living on the farm of Cabel Ide in Idetown. Some county officials, however, looked into Pegram's story and uncovered several discrepancies. A few believed that he had confessed to the crime merely for notoriety; others suspected that he was mentally imbalanced. "He is a nut," declared Captain Palmer with certainty.

On March 29, after spending three days in the city jail, Pegram was taken to the scene of the crime by City Detectives Connery and Deiter, Captain Palmer, and County Detectives Mitchell and Matthews. They wanted to gauge Pegram's reaction and determine whether or not he had fabricated his confession. According to the Scranton Republican, the party was besieged by two women, who shouted, "Look at the detectives holding that n----r! He ought to be lynched!" Their cries attracted others, until a crowd of over five hundred surrounded the detectives and the accused killer.

"Lynch him! Lynch him!" they chanted in unison, until it appeared that Pegram was about to be strung up from the nearest tree. Pegram clutched the arm of Detective Matthews. "Don't let them kill me!" he begged.

Realizing they had to act quickly, the detectives linked arms and formed a circle, with Pegram in the center. They forged through the mob, fending off rocks, bottles and insults hurled by the angry crowd, until they reached Luzerne Street.

The excursion to Continental Commons was an exercise in futility, and when it was over no one could agree on whether or not Pegram was telling the truth. "He is a low degenerate," stated Detective Connery to the press, "and his statements cannot be relied upon."

District Attorney George W. Maxey, however, begged to differ, pointing out that Pegram had accurately described the murder weapon and the injuries to Mary Quinn. Maxey claimed that all of the discrepancies in Pegram's story pertained to time and place names, and chalked up these discrepancies to Pregram's low intelligence. "He simply has his mental wires crossed, that's all," said Maxey.

Pegram was charged with murder, and his trial began on October 19, 1914, before Judge H.M. Edwards. Pegram was defended by court-appointed attorneys Harry W. Mumford and Michael J. Rafter. Mumford, interestingly, refused to argue against his client's sanity. "The negro is not crazy," he told the jury, "but he has the mind of a fourteen-year-old child. Therefore he is not wholly responsible for his actions."

The jury couldn't make a decision; they held out for nine days before finally reaching a verdict. Some of the jurors even wrote a letter to Judge Edwards begging him to put an end to the madness and let them return home. Meanwhile, indignation was running high in the press; it was pointed out that the cost of boarding and feeding the jurors had eclipsed $943, which was a rather exorbitant sum in 1914.

A Verdict at Last

On October 31, the jurors finally returned a verdict. They found William Pegram guilty of second-degree murder, and made a recommendation of "extreme mercy" for the killer. This recommendation was probably due to the fact that two of the holdout jurors were church pastors who had been standing their ground for acquittal. Matters were further complicated when defense attorney Mumford filed a petition for a new trial, claiming that Pegram had been the victim of an unfair and impartial jury. The jury foreman, Rev. Thomas Payne, who happened to be a Universalist minister, was the square peg who had caused the record-setting deadlock, which was the longest in county history.

Judge Edwards scoffed at Mumford's allegation and denied his request for a new trial. He did, however, bow to Payne's recommendation for leniency. And so, even though Pegram had not only confessed to murdering Mary Quinn but to sexually assaulting dozens of women and children as well, he was sentenced to five-to-twenty years in prison (he ended up serving eleven). One Scranton newspaper reported that Sheriff Ben Phillips didn't even bother handcuffing Pegram during the long journey from Scranton to the Eastern Penitentiary in Philadelphia, so strong was the county's desire to show "mercy" to the convicted killer.

The story of the brutal rape and murder of Mary Quinn should serve as a cautionary tale about mercy and leniency; incarceration did not reform Pegram or permanently alter his habits-- in 1925, almst immediately after his release from Eastern State Penitentiary, he was arrested again-- this time for raping an eight-year-old boy in Wilkes-Barre. He pleaded guilty to the charge and received a three year sentence and a $50 fine. After serving that sentence, Judge Jones decided to tack on the remainder of the original sentence for second-degree murder. Pegram was finally paroled again in 1940, leaving prison at the age of 69.

It is unclear when William Pegram died, and his last years have been lost to history. However, when his sister Ida passed away in 1951, it was reported that William was still living.

Sources:

Wilkes-Barre Times Leader, March 26, 1914.

Scranton Republican, March 27, 1914.

Scranton Republican, March 30, 1914.

Scranton Truth, Oct. 19, 1914.

Scranton Truth, Oct. 30, 1914.

Philadelphia Inquirer, Nov. 1, 1914.

Scranton Republican, Nov. 18, 1914.

Harrisburg Daily Independent, Nov. 20, 1914.

Scranton Truth, Nov. 21, 1914.

Scranton Republican, Jan. 5, 1925.

Wilkes-Barre Times Leader, Dec. 17, 1940

Did you enjoy this article? If so, then pick up a paperback copy of Pennsylvania Oddities, which features even more true stories of the strange from around the Keystone State, as well as more in-depth versions of some of the more spectacular stories shown on this blog. Only $14.95 and free shipping is available!

Comments

Post a Comment