The Burnside Skeletons, Part 1: Shamokin's First Mass Murder

Note: This is part one of a three part series.

In the early morning of Monday, October 7, 1974, daybreak revealed a large gathering on an embankment along Route 125, on the outskirts of Shamokin. To any early-bird motorist driving along this mountainous stretch of coal country near the village of Burnside, near the relay transformer station of the Pennsylvania Power and Light Company, it was evident that something momentous was about to take place; the assortment of police cars, fire trucks and other emergency vehicles might have evoked thoughts of a parade in the process of being organized, but the expression on the faces of the state troopers, city patrolmen and township police officers suggested that this was not a joyous occasion. Radios and walkie-talkies squawked and chirped like ominous birds, but the men standing in the damp autumn chill did not shiver-- for their blood was already running cold, and had been since it was reported that an anonymous caller had stumbled across a skeleton on Burnside Mountain.

By noon, the entire hillside was dotted with people: A pathologist who had arrived on the scene from Philadelphia, special officers from the Montoursville Troop F substation of the State Police, a handful of experts from the State Bureau of Criminal Investigation, the entirely of the Coal Township police, mine inspectors, and others who had come to witness the conclusion of a fifteen-month-old mystery.

Several hours earlier, just after 1:30 on Monday morning, a search had been made after months of wild rumors and speculation. But it was a phone call from an anonymous male source received by the Coal Township police at 10:30 on Sunday night that convinced local law enforcement to take to the woods, lantern in hand, in search of three girls who had been missing since July 19, 1973. The unidentified caller had told police that he had stumbled across a skeleton, protruding from a pile of rocks over an embankment, in an area heavily dotted with abandoned coal mines. But when the Coal Township officers went to have a look, the treacherous terrain and the inky darkness made them turn back. But now, as the sun rose over the mountains, the officers were intent on resuming their search for the body the unknown caller had seen. This time, they would be accompanied by dozens of other law enforcement officials.

When the skeleton was located by officers from Shamokin and Coal Township it was obvious that the remains were indeed human. But it was also obvious that if these bones were from one of the three teenage girls who had disappeared after a night of partying a year earlier, there ought to be two more nearby. The search now turned to the location of the lost graves. If this gravesite could be found, it would close the door on the mysterious disappearance of Margaret Long, age 16, her fifteen-year-old sister, Sherran (known to her friends as Sharon), and their fifteen-year-old friend, Carol Ann Taylor. And once this door was closed, it just might open the window and shed light on the mysterious circumstances surrounding their disappearance on the night of July 19, 1973.

District Attorney Samuel C. Ranck soon arrived on the scene from Milton, and was joined a few hours later by Deputy Coroner Quay Olley. As they waited for the arrival of Dr. Habert Fillinger, the assistant medical examiner of the Philadephia coroner's office, a tight police security was clamped on the area, as Captain David Martin and Lieutenant Steven Hynic of from the state police barracks in Montoursville took direction of the investigation. Route 125 was closed to traffic, with checkpoints established between Burnside and Gowen City.

The search dragged on for hours that day, and a call was placed to the Rescue Fire Engine and Hose Company of Shamokin at around 4:00, asking for lights at the scene. They were instructed to send just two people, along with floodlights, portable lighting units, and a 5,000-watt generator. "The police didn't want a crowd there," recalled Lt. John Smith of the fire company. "We had orders to keep it quiet."

As darkness crept in the searchers prowled through the underbrush, their faces reflecting the eerie glow of their lanterns, until they stumbled upon a pile of rocks near a ravine at the bottom of a 15-foot embankment. With no time to waste, they lifted the heavy stones, removing them one by one. Sure enough, their lanterns illuminated what remained of the victims of a mass murderer. But as they sifted through the tangle of bones, they wondered: Had the killer acted alone?

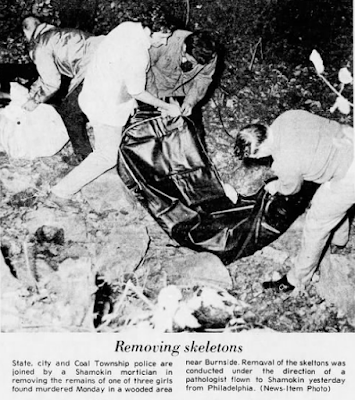

"That's it," announced Dr. Fillinger, as the last of the remains were placed inside a plastic blanket. It was around 8:30 in the evening. Though the discovery was unknown to most locals at the time, news of the find had already spread across the globe; Fillinger was joined at the scene by some of the best brains in the field of forensics-- Dr. Bernard Sims of the London Hospital Medical College, and Detective John Grant of the Bedfordshire Police Department of England. These men were in flown in by helicopter from Philadelphia, and their contributions to the case would ultimately lead to the guilty parties being brought to justice.

"This is going to shake up a lot of people," one of the officers remarked as the party returned from the ravine, their hands full of bags and plastic pouches. Inside these pouches were other items recovered at the scene: a leather belt, a pair of sandals, and women's underwear. "I have two girls myself, and I know how I would feel if these were my daughters."

"It was gruesome, just gruesome," remarked another officer to the large gathering of reporters who had been permitted past the police checkpoint. "It's certainly something no one ever expected would happen in our area."

The bags of evidence were put inside a station wagon, which carried the gruesome cargo to Shamokin General Hospital for further examination. Based on what he had observed at the gravesite, Dr. Fillinger believed that one of the victims has died of a severe injury to the front of the skull. The forensic experts from London agreed, and speculated that the victims had probably been killed at another spot, before being dragged to the makeshift grave. That the victims had been hastily buried and covered with rocks instead of being tossed down one of the countless mineshafts in the area led them to believe that the crime had not been pre-meditated. It was a crime of passion, and the hasty burial had been the result of panic on the part of the killer... or killers.

The Investigation Gets Under Way

On Tuesday, October 8, Coal Township Police Chief Jesse Weaver told reporters that state police were desperately attempting to trace the call that led to the discovery of the three skeletons on the mountain near Burnside. Weaver revealed that the call had come from a male they believed to be "under the influence of intoxicating beverages". Since Burnside Mountain had been a popular partying spot for local youths for generations, there was a possibility that the caller might have been a witness to the murders, and, therefore, the holder of crucial information.

At the same time, the state police were also pursuing leads the old-fashioned way-- by pounding the pavement. Trooper Charles McAndrew and investigators George Zelnick and Ray Topolski talked to people on the street and called five individuals in for questioning. They also interviewed the parents of the teenagers in an effort to find a clue that could lead them to the guilty party. According to witnesses, the girls were last seen around 9 p.m. on the night of their disappearance talking to some boys in a car on Shamokin Street.

Meanwhile, at the Shamokin hospital, Williamsport orthodontist Dr. Marshall Welch met with the parents of Margaret and Sherran Long. It was his belief that the remains were indeed those of the long lost girls. Sherran Long had braces, as did one of the skulls recovered from the makeshift grave. The Long family was wrought with conflicting emotions; they had always hoped that Margaret and Sherran were alive, but they weren't foolish enough to believe that they were. Yet they continued to investigate every possible lead offered by those who maintained that the teenagers had run away from home on that fateful day in 1973.

"We took a trip to West Virginia to a small town where the Taylor girl went once before," said the father, Paul Long. "We did everything within our power to try to find them. We called the Federal Bureau of Investigation but they didn't give us any satisfaction. They said the girls had to be kidnaped before they would enter the case." Their meeting with Dr. Welch at least afforded the Longs the peace of no longer having to make long-distance trips in the futile attempt to locate their missing daughters. "It is hard to face a thing like this, but we have to face the facts," he concluded.

As for the father of Carol Ann Taylor, he was not at all ready to put the matter to rest. Understandably, he wanted to see the culprits brought to justice. "We didn't sleep all night worrying about it," David Taylor told reporters. "You wonder what kind of animals would do something like this." Identification of his fifteen-year-old daughter's remains was made through a Shamokin High School class ring given to her a former boyfriend, and another ring that was given to her by older sister, Diane.

Satisfied of the identity of the victims, Dr. Herbert Fallinger brought the remains to Philadelphia to conduct further studies in order to determine how exactly the girls had met their demise. And what he uncovered was shocking. Fallinger believed that some sort of acid had been poured over the bodies to hasten their decomposition. However, it was unclear whether this act had occurred immediately after the murders, or at some later point. If the latter were correct, it would imply that the killer, or killers, were still in the vicinity.

On October 11, Chief of Police Gerard Waugh of the Shamokin city police force admitted that his department had been exploring the possibility of mass murder since March, when Officer Bobby Olcese heard a rumor that the girls had been murdered and tossed down an old mine shaft. An extensive search of over thirty abandoned mines in Coal and Zerbe townships was conducted by Clarence "Moochie" Kashner, a state mine inspector, but yielded no results. Kashner, assisted by veteran miners Robert Witmer and Donald Lorenz, explored old mines as far away as Trevorton and Excelsior, and were aided in their efforts by state forestry officials who provided them with the lumber, ladders and rope needed to shore up the abandoned workings. It was a perilous task, and everyone involved in the search did it without pay, and without any regard for their personal safety.

"We knew that if the bodies were in any of those mines, we'd find them," Kashner declared.

Coincidentally, on the morning the skeletons were found, Kashner, along with state forestry officials J.L. Rohrer and Guy Ditty, were also on Burnside Mountain, getting ready to explore a mine near the spot where the remains were found.

The Hippie and the Sports Hero

All of Northumberland Couty was abuzz on Tuesday, October 15, when Trooper McAndrew announced that two arrests had been made in the case, and hinted that a third arrest might be forthcoming. Taken into custody and arraigned on a charge of criminal homicide were 23-year-olds Joe Ziemba and Sebastian Yost, both of Shamokin. Yost was arrested at his home by Cpl. Adolph Blugis of the Shamokin sub-station of the state police, while Ziemba was picked up by Officer Olcese at a job site in Kulpmont. They were taken to the office of District Magistrate John Moore for arraignment.

News of the arrests spread like wildfire, and a line of over more than two hundred curious onlookers stretched around Rock Street in Shamokin outside the magistrate's office, awaiting their first glimpse of the accused killers. Sebastian Yost was the first to arrive and was promptly whisked inside by Cpl. Blugis, giving the crowd just enough time to take in Yost's colorful bell-bottom jeans, long, unkempt hair and sideburns that extended well below his jawline. A few minutes later Yost re-emerged, and was committed to Northumberland County Prison without bail.

A short while later, all eyes turned to the squealing of tires as two police cars ran the red light at Rock and Independence streets. The crowd stretched their necks as the cruisers parked in front of the magistrate's office, and a collective gasp swept through the crowd when they identified the second accused killer. Joseph Ziemba was no stranger in Shamokin; he had been a star basketball player in high school before joining a local league as a young adult. Just one year earlier, Ziemba had dazzled fans by scoring 85 points in a single Anthracite Basketball League game. After his arraignment Ziemba was committed to Union County Jail without bail.

The following week, the remains of the three victims were returned from Philadelphia after Dr. Fillinger had completed his examination. Based on his examination, it appeared that the fatal blow that had fractured the front of Carol Ann Taylor's skull had been caused by a tire iron, and that the Long sisters had most likely been strangled-- possibly by the killer's bare hands. The bones of Carol Ann Taylor were laid to rest in St. Edward's cemetery, while the remains of the Long sisters were interred at Odd Fellows Cemetery on Trevorton Road. On the investigation front, Trooper McAndrew and Lt. Stephen Hynick of the state police refused to divulge details about the third person of interest in the case, but hinted that the suspect had been kept under close surveillance since the arrests of Yost and Ziemba, but admitted that all the victims had been acquainted with the suspects prior to their deaths, and that one of the girls had been casually dating one of the accused killers.

On October 23, it was reported that the preliminary hearings would be postponed because of Sebastian Yost's inability to procure legal representation. Though his family had requested a court-appointed lawyer, it seemed that no lawyer in the county wanted to take the case. One local attorney who had been asked by the county to fill the role replied that he would find it impossible to fairly represent Yost in court-- he had simply been too disgusted and horrified by the cruelty of the triple murders. However, the county public defender, Frank Garrigan, did agree to represent Joseph Ziemba. It remains unclear whether this was because Garrigan believed that his client played a minor role in the affair, or simply because he believed that his client's reputation as a local sports hero would work to his advantage. Two days later, Judge Michael Kivko and Judge Frank S. Moser signed an order appointing two local attorneys to represent Yost. Whether they wanted to or not, it was up to Roger Haddon and Gerald Malinowski to represent the accused killer.

Authorities Arrest Honeymooner, Sordid Details Emerge

On the eve of the preliminary hearing for Yost and Ziemba, a warrant was obtained from District Magistrate Moore by Troopers McAndrew and Clifford Artman for the arrest of the third suspect, 20-year-old Roland "Rocky" Scandle, a graduate of Our Lady of Lourdes Regional High School in Shamokin. Just before midnight, Lt. Hynick and Trooper McAndrew knocked on the door of Scandle's apartment at 1301 West Walnut Street in Shamokin and took him into custody without incident. When he appeared at the arraignment he was asked by the magistrate if he had a job. "Yes, but not after today," Scandle replied. Scandle was then asked if he was married, and the accused killer informed Moore that he had been married just one month earlier. This was not news to the state police, however; the reason they had waited so long to make the arrest was because Scandle and his wife were out of the country on their honeymoon. After leaving the magistrate's office, Scandle was transported to the county prison in Sunbury.

The following day, Joseph Ziemba testified as a witness for the commonwealth against his friend, Sebastian Yost. Because of the sensational nature of the case, the preliminary hearing, which normally would've taken place in Magisterial Court, was moved to courtroom number two at the county courthouse in Sunbury. When asked by District Magistrate Moore how he would plead to the charges against him, Yost replied, "not guilty".

Ziemba was the fifth witness to testify that afternoon, and his testimony left the two hundred spectators packed inside the courtroom in shock.

Under direct examination by District Attorney Ranck, the young man told of a murder pact between the three men after a drinking party in the woods went horribly awry. According to Ziemba, he and Sebastian Yost had been hanging out at the Market Street Park on the evening of the murders, where they were later joined by Roland Scandle. After cruising downtown for a while in Scandle's car, a green 1973 Chevelle, they stopped at a liquor store for a bottle of wine. "Scandle saw one of the Long girls," he explained. "He stopped the car on Eighth Street and called Sherran and asked her if she wanted a drink. There were four girls, but I only knew three of them." The six then drove to Ghezzi's, where one of them purchased two six-packs of beer.

Ziemba testified that they parked the car about a half mile from Burnside, after turning down a dirt road. "We were all outside the car drinking and talking," he said. "Then Scandle and one Long girl had sexual relations. They went into a bush along the road and returned about thirty minutes later."

Apparently, the trouble began after Margaret called her 15-year-old sister "a pig" for what she had just done. As the Long sisters were shouting at each other, Ziemba grabbed Margaret and pushed her against Roland Scandle's car. After regaining her composure, she and Carol Ann walked away.

"Sebastian and I called for them to come back," continued Ziemba. He said the girls were crying, and one of them threatened to go to the police.

"It looks like we're going to have to kill them so they don't tell the cops," Scandle allegedly told Ziemba and Yost. A few moments of awkward silence passed. "I guess it's about time we do it," Scandle insisted.

According to Ziemba, it was Sebastian Yost who strangled Sherran Long using Scandle's belt. "He drew it tight around her neck for about five minutes and then she fell to the ground," explained Ziemba. Yost then handed the belt back to Scandle, who murdered Margaret in the same manner. Yost and Scandle turned to Ziemba. "Now it's your turn," said Scandle.

Ziemba told District Magistrate Moore that he didn't want to carry out the murder of Carol Ann Taylor. Nonetheless, he tackled the teenager, beat her, and stuffed her unconscious body into the trunk alongside the bodies of her friends. Scandle drove about a quarter mile down the road to an open area, but when he opened the trunk, he saw that Taylor was still alive.

"Scandle picked up a rock and hit her over the head," declared Ziemba. After pushing the bodies over an embankment into the woods, they drove to a car wash in Green Ridge and washed out the trunk . The three men agreed to meet the following day to determine what to do about the dead bodies.

"We went to Jones Hardware and Scandle bought two gallons of some chemical that cost six or seven dollars," said Ziemba. "Scandle had a pick and shovel and the three of us went back to the area. We put the bodies between rocks and then put dirt and leaves on top of the rocks. Then we put a boulder over the leaves and dirt."

NEXT: The Identity of the Mysterious Caller Revealed

One interesting piece of new information to emerge from the first day of the hearing was the testimony of the man who had been the anonymous caller who telephoned the Coal Township police. Stay tuned for next week's article, Part II of "The Burnside Skeletons: Shamokin's First Mass Murder".

Sources:

Shamokin News-Item, Oct. 7, 1974.

Sunbury Daily Item, Oct. 8, 1974.

Shamokin News-Item, Oct. 8, 1974.

Sunbury Daily Item, Oct. 9, 1974.

Shamokin News-Item, Oct. 11, 1974.

Shamokin News-Item, Oct. 16, 1974.

Sunbury Daily Item, Oct. 17, 1974.

Sunbury Daily Item, Oct. 23, 1974.

Shamokin News-Item, Oct. 25, 1974.

I've never heard of these stories from my area. Only Tracy Kroh.

ReplyDeleteI grew up in Kulpmont, so I write a lot about our area. I knew about this case from a young age because my mother used to "hang out" with Joseph Ziemba. And, in another bizarre twist of fate, our next door neighbor was Mr. Blugis (the state trooper who actually made the arrests). Small world, I guess!

DeleteThis post is absolutely fascinating—what a captivating dive into local history and mystery! The Burnside Skeletons story grabs your attention right away, blending historical intrigue with a touch of the eerie. It’s amazing how places carry so many hidden stories waiting to be uncovered. Preserving or restoring these historic spaces adds another layer of connection to the past. R for Remodelers specializes in thoughtful renovations that respect the character of older buildings while updating them for modern use—perfect for properties with stories as rich as this one.

ReplyDelete