The Burnside Skeletons, Part 3: Shamokin's First Mass Murder

This is the last of a three part series. Click to read Part 1 and Part 2.

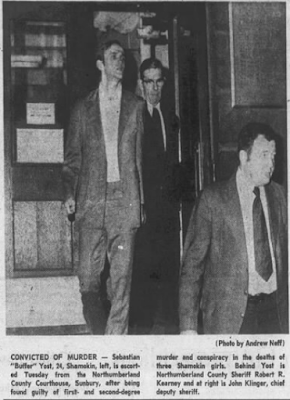

The jury of nine men and three women began deliberations at 12:30 p.m. on Tuesday, July 1 to decide the fate of Sebastian Yost. After eight hours and seventeen minutes of deliberation, they returned to the courtroom to render the verdict. Yost wept and thrashed his head violently from side to side as the court clerk, Harry Wallick, read the decisions. They had found Yost guilty of murder in the first and second degrees. The first-degree murder conviction alone for the killing of 15-year-old Sharon Long guaranteed a sentence of life imprisonment.

Patricia Yost, the killer's 20-year-old wife, sobbed as her husband was led away by Sheriff Robert Kearney. On the other side of the courtoom, Mr. and Mrs. Paul Long sighed with relief. Yost tried to take a swing at a photographer outside the courthouse with his one uncuffed hand, but missed. Yost's attorneys filed a motion seeking a new trial for their client, which Judge Moser accepted the following week. But this would have to wait until all the testimony could be transcribed by Judith Dobies, the court reporter. When the transcription was finally complete, it clocked in at a hefty 691 pages.

The Sentencing of Sebastian Yost

Scandle's attorneys, Roger Wiest and Jack Youngkin, wasted no time making preparations for the trial of their client. They promptly filed another application for change of venue, and, in early September, demanded a psychiatric evaluation of the commonwealth's star witness, Joseph Ziemba. The change of venue request seemed to have merit; four witnesses who had testified in Scandle's previous attempt to have the trial relocated urged Judge Kivko to consider the fact that many local residents were angry, convinced that Ziemba was "getting off easier" than Scandle and Yost. These witnesses included prothonotary clerk Corrine Wetzel and deputy prothonotary William Jacoby, who said that he feared for the safety of any juror who might vote to acquit Scandle. When the district attorney objected to this statement, Jacoby declared that if charged with the same crime, he wouldn't want to be tried by a Northumberland County jury.

November was filled with twists, turns and legal wrangling. The month began with the dismissal of Yost's motion for a new trial by Judges Moser and Kivko, who insisted the court had not erred by refusing to allow Yost's defense to cross-examine the commonwealth's star witness, Joseph Ziemba. Yost was ordered to appear for sentencing on the morning of November 13.

On November 7, Lebanon County judge Thomas Gates dismissed the motion filed by Scandle's attorneys, Wiest and Youngkin, to have Joseph Ziemba subjected to a psychiatric examination. The judge also dismissed a second motion, asking for the release of tapes containing statements which the defense insisted would be crucial to proving their client's innocence. The state Supreme Court, however, permitted Scandle to be tried in Lebanon County.

Despite the commonwealth's promise to delay sentencing until all three defendants had been tried, Yost was sentenced to life in prison by Judge Moser on the morning of November 13, with additional terms of 10-20 years on each of the two counts of second-degree murder and 5-10 years for criminal conspiracy. The sentences would run concurrently. When asked if he had anything to say, Yost, wearing a blue t-shirt with a pack of cigarettes in the pocket and denim jeans, said "no".

The Trial of Roland Scandle

The jury selection process for the Scandle trial got under way on Monday, November 17, 1975 and the testimony began on Wednesday with the mother of Carol Ann Taylor taking the witness stand. She had answered just one question before falling into a swoon. "I can't go on," she murmured as she was assisted from the courtroom. Judge Gates immediately called a ten-minute recess. After composing herself on a sofa in the hallway, Mrs. Taylor returned to the witness stand and gave a heart-wrenching account of the last time she had seen her daughter alive.

Although most of the morning was a repetition of the Yost trial, some new evidence was presented, including never-before-seen photographs of the skeletons and an assurance from Dr. Fillinger that his conclusions about the nature of the girls' fatal injuries had been confirmed in a cooperative study made by Dr. Wilson Trodman, a world-renowned physical pathologist from Lancaster. When Mrs. Long was cross-examined and questioned about her mental health in the defense's attempt to discredit her testimony, she admitted that she had been a patient at Geisinger Medical Center for three weeks in 1973, before being committed to the Danville State Hospital. As it turned out, she had been in a psychiatric facility from March to July of that year.

The following morning, Joseph Ziemba took the stand and his chilling details about the killings drew horrified gasps from the crowd of courtroom spectators. Although Ziemba's story had been well-rehearsed by this time through several re-tellings, it was the first time many residents of Lebanon County had heard it. When Robert Reichwein, who was now estranged from his wife, took the stand, he claimed that he had not gone to the police because he "feared for his own life" and the life of his family-- one more detail that had never surfaced until that time.

The defense, which had obtained transcripts of the tape recorded conversation between Trooper McAndrew and Ziemba-- the same tapes they had sought access to earlier but were denied-- recalled McAndrew as a witness and grilled him about Ziemba's many inconsistent statements. McAndrew admitted that there were indeed inconsistencies, but insisted these inconsistencies didn't alter the key facts of the case.

The defense wrapped up its case on Saturday by calling their own client to testify. Scandle's father, Roland, Sr., had just finished his own testimony, telling the court that his son couldn't have taken part in the murders because they were working together on a job site in Lycoming County on the night of July 19, 1973. The father claimed they were building a roof in Montgomery, and it was already past 9:00 p.m. by the time they had finished. He recalled the date because he had received a shipment of building materials the day before. Jean Appel, a clerk at the Knoebel Lumber Company in Elysburg, provided a copy of the invoice showing that lumber, cement, sand and gravel had been delivered to the Scandle home on July 18. While this may have been true, it was not proof of Scandle's whereabouts on the night of the murders.

When the defendant took the stand in his own defense, he reiterated his father's story and a final witness, a neighbor named Jean Landau, testified that she had walked past the Scandle home on the night of July 19 and saw the defendant inside.

The jury began deliberation on Monday. After four hours and fifteen minutes the panel of six men and six women reached a verdict, finding Roland Scandle guilty on three counts of first-degree murder and one count of criminal conspiracy. When deputy court clerk William Viall announced the verdict, Scandle's wife and mother erupted in tears. Attorney Wiest vowed to file an appeal, though he admitted he did not know on what grounds the appeal would be based.

The Sentencing of Joseph Ziemba

Ziemba, by confessing to the murders and accepting a plea bargain, waived his trial and awaited the day of his sentencing, which had been scheduled for the following month. He would be sentenced to a prison term of 10 to 20 years on each of the three counts, but it was up to a judge to decide whether these sentences would run concurrently or consecutively. For the former basketball star, this was ostensibly a life-or-death decision-- he could be a free man in as little as ten years, or he could die in prison of old age.

On Thursday, December 4, 1975, the sentence was handed down by Judge Michael Kivko. Ziemba was sentenced to three concurrent terms of 10 to 20 years. A fourth sentence for conspiracy to commit murder would also be served concurrently. Because he had already been in prison for 14 months, some veteran court reporters predicted that, with time served and good behavior, he could be out on parole as early as fall of 1984. Other experts, however, believed that the violent nature of the crimes would prevent Ziemba's parole, delaying his release until 1995.

After sentencing, Ziemba was returned to the county jail to await transfer to Rockview State Correctional Institute.

The Aftermath

Though it had been held in Lebanon, the Scandle trial alone had cost the taxpayers of Northumberland County $14,000-- a bill that was not paid off by the cash-strapped county until 1977. That same year, the state Supreme Court dismissed Scandle's appeal for a new trial, though it agreed to review the matter in the spring of 1979, amid accusations that the commonwealth had kept exculpatory evidence from the defense. According to Scandle's attorney, Roger Wiest, a tape recording of Walter Leasure, who did not testify during any of the trials, had been withheld from the defense. Northumberland County's assistant district attorney, R. Michael Kaar, countered that, based on the rules of evidence, Wiest did not qualify for access to the tape because Leasure never took the witness stand. The state Supreme Court ruled in Kaar's favor. Scandle, who was now serving his sentence at a state prison in Dallas, filed another appeal in 1980. He lost.

On August 30, 1984, Joseph Ziemba became eligible for parole. The state Probation and Parole Board denied the 33-year-old inmate's request. According to Joseph Long, assistant to the state board chairman, the denial was based on the brutality of the 1973 slayings, coupled with the fact that Ziemba had been less than a model inmate at Rockview. The board did state, however, that he could apply for parole again the following October if he chose to participate in some of the prison's "therapeutic programs".

After his request for parole was denied a second time, Ziemba apparently resigned himself to his fate. In November of 1986, he shunned an opportunity for early release, telling the parole board that he wished to remain in prison until the expiration of his sentence in October, 1994. According to Long, Ziemba had "adjusted poorly to prison life", adding that inmates occasionally request to remain in prison because they are unable or unwilling to comply with parole stipulations. It must have been a bitter disappointment to the commonwealth's former star witness when he realized that, by striking a bargain with the state, he was destined to be an outcast no matter which side of the prison gate he was on. He changed his tune by 1990, however, but his request for early release was denied. Once again, the explanation for the board's denial centered around Ziemba's refusal to participate in prison rehabilitation programs. Another request for parole was denied in 1992.

Ziemba served out the remainder of his term and, upon his release, moved to an apartment above the Guarantee Trust Building on Third Street in Mt. Carmel. In 1996 he was arrested for selling prescription drugs to undercover cops. He died on September 19, 2003 at the age of 51 of undisclosed causes and was buried at Odd Fellows Cemetery in Shamokin, sharing a final resting place in the same graveyard with tow of his victims, Margaret and Sherran Long.

As for Sebastian Yost, who has no possibility of parole, he continues to serve his life sentence at Mahanoy State Correctional Institution in Frackville, Schuylkill County. He is currently 70 years of age. Roland Scandle remains at Dallas State Correctional Institution in Luzerne County, where he is one of some four hundred inmates who are serving life without the possibility of parole. He is currently 67 years of age.

Sources:

Shamokin News-Item, Oct. 7, 1974.

Sunbury Daily Item, Oct. 8, 1974.

Shamokin News-Item, Oct. 8, 1974.

Sunbury Daily Item, Oct. 9, 1974.

Shamokin News-Item, Oct. 11, 1974.

Shamokin News-Item, Oct. 16, 1974.

Sunbury Daily Item, Oct. 17, 1974.

Sunbury Daily Item, Oct. 23, 1974.

Shamokin News-Item, Oct. 25, 1974.

Sunbury Daily Item, Nov. 1, 1974.

Shamokin News-Item, Nov. 1, 1974.

Shamokin News-Item, Nov. 2, 1974.

Sunbury Daily Item, Nov. 6, 1974.

Sunbury Daily Item, Nov. 8, 1974.

Shamokin News-Item, Nov. 13, 1974.

Shamokin News-Item, Dec. 17, 1974.

Shamokin News-Item, Jan. 11, 1975.

Shamokin News-Item, Jan. 24, 1975.

Shamokin News-Item, March 27, 1975.

Shamokin News-Item, April 4, 1974.

Sunbury Daily Item, June 3, 1974.

Sunbury Daily Item, June 24, 1975.

Sunbury Daily Item, June 26, 1975.

Sunbury Daily Item, June 27, 1975.

Smaokin News-Item, June 28, 1975.

Shamokin News-Item, June 30, 1975.

Shamokin News-Item, July 1, 1975.

Sunbury Daily Item, Aug. 22, 1975.

Shamokin News-Item, Sept. 8, 1975.

Shamokin News-Item, Nov. 7, 1975.

Shamokin News-Item, Nov. 13, 1975.

Shamokin News-Item, Nov. 19, 1975.

Shamokin News-Item, Nov. 20, 1975.

Shamokin News-Item, Nov. 22, 1975.

Sunbury Daily Item, Nov. 25, 1975.

Sunbury Daily Item, Dec. 4, 1975.

Sunbury Daily Item, Dec. 21, 1977.

Sunbury Daily Item, April 21, 1979.

Sunbury Daily Item, Sept. 19, 1984

Sunbury Daily Item, Nov. 18, 1986.

Sunbury Daily Item, April 10, 1990.

Comments

Post a Comment