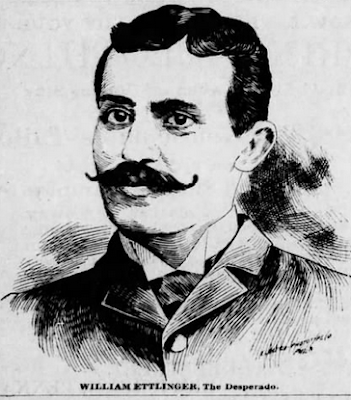

William Ettlinger, the Desperado of Woodward

One of the most exciting chapters in the history of Centre County (not involving Penn State football, of course) took place in 1896 with the shooting of notorious desperado William Ettlinger, who is, arguably, one of the most famous outlaws central Pennsylvania has ever produced. What makes this chapter in Centre County history so remarkable is that it features a slain lawman, a brave posse with an incredibly large supply of ammunition and an allegedly stolen corpse.

The chain of events which ultimately and directly led to Ettlinger's death began in August of 1895 in the tiny mountain village of Woodward, where Ettlinger administered a severe beating to his father-in-law, Benjamin Benner. Ettlinger was arrested and placed under $250 bail, and was scheduled to stand trial in November of that same year.

Ettlinger's bondsmen were local citizens Daniel Engle and Isaac Orndorff, and when Ettlinger failed to show up for his hearing, Judge Love issued a bench warrant for the brute's arrest and declared Ettlinger had forfeited his bond. It was Constable Edward Mingle, of nearby Aaronsburg, who was tasked with the duty of serving the warrant to the accused.

Ettlinger, of course, wasn't very happy about losing $250, but he was even less happy to learn about the bench warrant. As a man with a shady past and a far-reaching network of criminal lowlife friends, Ettlinger learned in advance that Mingle was on his way to serve the warrant. He put out the word that he would kill Mingle on sight, then he armed himself with several revolvers, pistols and his trusty Winchester rifle and took flight into the mountains, where he managed to hide for several weeks.

All of this occurred during an election year, and John Barner won the election for constable by promising the voters of Haines Township that he would capture the notorious fugitive, whom many believed had murdered his first wife. Others claimed that Ettlinger had spent the previous few years collecting poison, which he hoped to release into the village's water supply. His second wife, and future widow, claimed that Ettlinger had also amassed a large quantity of dynamite and other explosives.

After being sworn into office in spring of the following year, Barner's first official order of business was to travel from Bellefonte to Woodward to serve the warrant upon Ettlinger and attempt to succeed were Edward Mingle had failed.

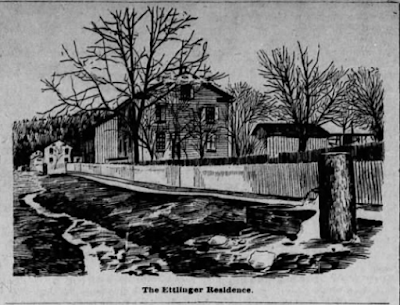

On Thursday afternoon, March 5, 1896, Constable Barner arrived at Woodward and, well aware of his prey's dangerous reputation, deputized local residents C.G. Motz and John Hosterman. The three men then went hunting for William Ettlinger, who was believed to be at his home. When they knocked on the door they were refused admission by Ettlinger's wife. Meanwhile, the fugitive loaded his rifle and locked himself in an upstairs bedroom with his two children.

Constable Barner kicked down the front door and the three men entered the home, only to find that Ettlinger had closed and locked the door leading to the stairs. Barner was able to smash the wooden panel and had crawled halfway through the hole when the blast of a shotgun reverberated through the house. The constable's head was thrown back violently, blood pouring from the gaping wound. He died almost instantly.

Motz and Hosterman immediately retreated, leaving Barner's body still hanging from the busted door panel, while Ettlinger reloaded his weapon. Meanwhile, a neighbor by the name of Frank Geiswhite happened to be looking out his window from across the street when he noticed Ettlinger's rifle pointed straight at him. Luckily, he managed to duck just in time, but not before the fugitive's blast struck him in the shoulder.

A short while later the two bondsmen, Daniel Engle and Isaac Orndorff, were approaching the Ettlinger house to render their assistance when the desperado began shooting at them. Neither man was struck, but as the afternoon wore on Ettlinger stood his ground from the upstairs bedroom of his home and took shots at anyone who tried to approach the property. Two shots were fired at the school house, with children still inside. He also fired a shot that struck the home of Mrs. George Miller, shattering her window. Another shot grazed a man named John Musser in the neck.

At five o'clock that even the citizens of Woodward telegraphed Sheriff Condo in Bellefonte, begging for immediate assistance. Condo, with a force of fifteen lawmen and deputized citizens, grabbed their guns and hopped the first train to Coburn, arriving at Woodward at eight o'clock. By this time, a mob of five hundred angry locals had surrounded the Ettlinger place, while another two thousand out-of-towners raced to the scene. Demands for surrender were given sporadically, to which Ettlinger shouted his unchanging reply, "You'll never take me alive!"

As the night progressed, the outlaw kept his pursuers on their toes by firing off the occasional shotgun or pistol. Some of the villagers responded in kind. The Altoona Tribune reported that more than 1,000 rounds were fired back and forth during the March 5 stand-off, and the shooting continued for hours, until the citizens ran out of ammunition. Nearly every structure in Woodward bore scars from the wild night of whizzing bullets and rifle balls.

|

| Map of the site of the Woodward shootout |

The standoff continued into the next day, when a handful of men from Woodward ransacked Bellefonte in search of more ammunition. Meanwhile, Sheriff Condo telegraphed for more men. By sunrise, the sheriff had deputized sixteen locals and began to formulate a bold plan to charge the house. The charge came at 6:30 in the morning, but the men were repelled by a fusillade of gunshots from Ettlinger and were forced to retreat. From 6:30 to 11:00 not a single shot was fired. Had William Ettlinger finally run out of ammunition? Had he chosen to end the standoff by taking his own life? And what about the lives of his innocent young children? Or was the death-crazed desperado merely resting, preparing for yet another day of mayhem?

By noon the mob, which still surrounded the Ettlinger home, could not endure the tension. They came to the collective conclusion that the madness had to come to an end, here and now, even if it meant risking their own hides. They all agreed that the time had come to make one massive charge; the entire village of Woodward against one deranged lunatic. But someone had a different idea. Why not try setting fire to the wooden frame building?

Moments later the entire structure was engulfed in flames. The fugitive's wife and children were smoked out of Ettlinger's smoky lair and whisked away, and it seemed that it was just a matter of time before Ettlinger himself walked out of the inferno with arms raised in surrender. But this would not be the case.

William Ettlinger walked out, all right, but with a curious expression etched onto his haggard, sleep-deprived face. The members of the posse looked at each other, wondering what was about to happen next. Sheriff Condo repeatedly ordered the outlaw to surrender, but Ettlinger stood on the porch and laughed maniacally. He then drew a large revolver, pointed the barrel at his temple, and pulled the trigger.

A barrage of footsteps sidestepped the outlaw's crumpled body, as deputies raced into the inferno to salvage the remains of Constable Barner. Interestingly, since no photographs of Ettlinger were known to exist, the drawing of him that was featured in numerous newspapers throughout the country in 1896 was sketched by an artist from Lewisburg who used a photograph of the outlaw's corpse as a model.

John Barner, a man of 37 years, with a wife and several children, lost his life in an attempt to keep his campaign promise to the citizens of Haines Township. His loss was felt deeply and profoundly throughout the county, and he was laid to rest as a hero. In December of 1896, a six-foot-tall monument was erected in Woodward in memory of the brave constable.

As for William Ettlinger, his relatives refused to have anything to do with his body. It was collected by the Overseers of the Poor, placed into a cheap pine coffin, and hauled in a farm wagon to a lonesome spot about a half mile east of Woodward, where it was unceremoniously buried in an unmarked plot covered with stones. A few days later, it was reported that his body was stolen from the grave by medical students from Philadelphia, but this was later revealed to be a hoax and so the mortal remains of William Ettlinger remained buried temporarily beneath a pile of stones somewhere in the lonesome wooded area known to the locals as the Penn Valley Narrows.

Today, a gravemarker can be found Woodward Union Cemetery bearing the names of William, his wife and children. After the Woodward shootout, the outlaw's widow issued an appeal to have her husband buried in the cemetery, and the re-interment took place on April 28, 1896. It is unclear who created the handsome monument which currently stands at Woodward Union Cemetery, and whether or not the misspelling of the outlaw's name was intentional or accidental.

Ettlinger's widow, Mary Jane Elizabeth Benner Ettlinger Fultz, was also an interesting character. Though she maintained that she had no involvement in her husband's nefarious affairs, many locals refused to believe her story. A few years after William's suicide, Mary Jane married Edson Fultz, another shady character with an unsavory reputation. In March of 1905, Mary Jane and Edson were arrested, along with three other local misfits, for robbing the Eby brothers, Henry and Martin, who were wealthy, elderly bachelor farmers who did not believe in keeping their life savings in a bank. Edson and Mary Jane, who worked as a housekeeper for the Eby brothers at the time, both pleaded guilty to the crime. Edson was sentenced to two years in prison, but was pardoned one year later.

Mary Jane died in May of 1909 at the age of 38.

Sources:

Wilkes-Barre Times Leader, March 6, 1896.

Altoona Tribune, March 7, 1896.

Altoona Tribune, March 10, 1896.

Perry County Democrat, March 11, 1896.

Lewisburg Journal, March 13, 1896.

Sunbury Daily Item, Dec. 23, 1896.

Philadelphia Times, March 11, 1896.

Altoona Tribune, May 2, 1896.

Snyder County Tribune, March 3, 1905.

Comments

Post a Comment