The Legend of Margaret Duncan's Burying Ground

(Note: Audio version of this story is available on the Pennsylvania Oddities Podcast)

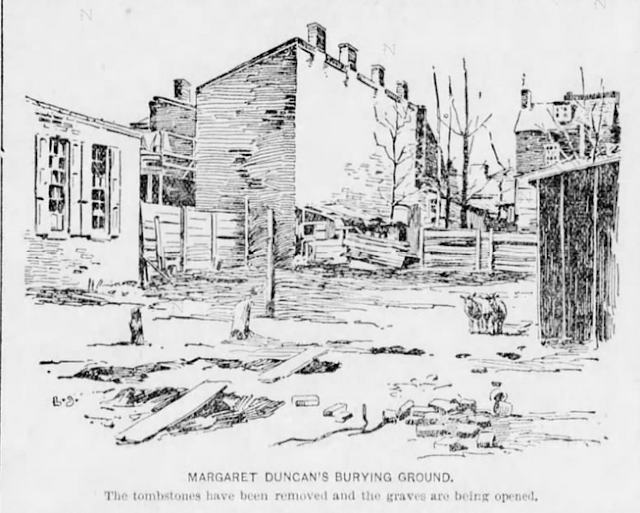

In the waning years of the 19th century, the city of Philadelphia lost one of its most curious and morbid historical landmarks-- an obscure graveyard hidden in the center of an urban jungle, where the bones of forgotten Philadelphians slumbered for generations, until their remains were mysteriously and unceremoniously disinterred and moved elsewhere.

This strange cemetery had an equally strange history, and attached to the graveyard was a curious legend about the plot's namesake, Margaret Duncan.

"Margaret Duncan's Burying Ground", as it was known to generations of city-dwellers who lived in the rough Scots-Irish neighborhood known as Queen Village, was located off Bainbridge Street, just east of Fourth Street. There was no formal entrance to this graveyard; in order to access the enclosure, visitors had to squeeze though a narrow passageway between the cheap tenement housing known at the time as Lester Place (not to be confused with the present housing development in Northeast Philadelphia with the same name).

By the 1890s, Margaret Duncan's Burying Ground had become a neglected and wretched place. Dank and dark, the twenty or so decaying tombstones within the drab half-acre enclosure were concealed from view behind the ivy-covered brick walls of the surrounding buildings which kept it hidden from the busy world. Only those who lived in the immediate vicinity knew about the place, and many of the few who knew about it had a difficult time accessing it.

Behind one of the ramshackle homes, just three feet from the back door of 5 Lester Place, rested a broken, sunken slab inscribed with two names:

In memory of Isaac Duncan, who departed this life March 20th, 1770, aged 52 years.

And,

Margaret Duncan, Aged 79 years. Precious in the sight of the Lord is the death of His saints.

Isaac Duncan was once one of the wealthiest merchants in the city, and was one of the original residents of the Southwark neighborhood of Queen Village. During the Colonial Era, Queen Village was a suburb of Philadelphia, and Duncan purchased several acres of property there and built an impressive home for himself and his wife. As for Margaret Duncan, her fame rests on a strange contract she made with God while facing death on the high seas.

A Brow as Black as a Thundercloud

This strange event occurred many years before the Revolution, when her husband was the owner of a humble little grocery store on Water Street. After the Duncans had managed to squirrel away a few dollars, Margaret decided that she wanted to return to Ireland to visit some relatives which she and her husband had left behind when they emigrated to America. In the fall of 1760 she took passed for Ireland aboard one of the slow-sailing cargo vessels of the day, a ship piloted by an evil captain described as "a man with ways as devious as the sea and a brow as black as a thundercloud".

Although nothing remarkable took place on the voyage to Ireland, during the return trip Margaret and several of the other passengers began to suspect that the captain was up to no good. After several heavy storms had swept the ship's deck, a poor immigrant woman with a baby in her arms confronted the captain about his nautical ability. He cursed the woman and struck her with his fists until she crumpled to the deck. This act of brutality was just the beginning; shortly afterward the captain-- with the aid of his crew-- proceeded to rob the passengers of what little money they had. To make matters worse, the ship was several days behind schedule and provisions were running perilously low.

During a third night of intense storms, the ship began to take on water until it seemed that all on board were doomed to a watery grave. The following morning the passengers were horrified to discover that, sometime during the night, the captain and crew had piled into the vessel's lone lifeboat and abandoned the ship. They had taken with them what little food and fresh water remained, leaving Margaret and the rest of the passengers to die of either drowning or starvation-- whichever happened to come first.

A Ghastly Lottery

On the following day, which was a Thursday, a meeting was held on deck, in which it was decided that one of the passengers must sacrifice his or her own life in order to furnish food for the others. A drawing was held, and scraps of paper distributed to the passengers were all blank except for one, upon which was written the dreaded words, "For the lives of others you are sacrificed".

It was Margaret Duncan who drew the death card. Without a word she stumbled back to her cabin to await her fate, and to pray as she had never prayed before. She pleaded with her Creator, promising that-- if her life was spared-- she would erect in Philadelphia a church and devote the rest of her life to serving others. Not more than an hour later the doomed ship came into contact with another vessel, and the passengers were evacuated.

When Margaret arrived safely in Philadelphia she told her miraculous story to all who would listen. Although she did not yet possess the funds needed to erect a new church, she devoted all of her energy to the Associate Reformed Church, where she was a member and her son-in-law, Reverend David Talfair, was the pastor. After Isaac's death in 1770, Margaret took over the grocery store on Water Street and turned her husband's already thriving business into an even greater success. It was said that every Thursday (the day of the week she had been rescued at sea) Margaret would lock herself in her room and spend the day in fasting and prayer.

By the time of her death in 1802, Margaret Duncan was one of the wealthiest citizens in Philadelphia and arguably one of the shrewdest businesswomen in the country. During her later years she bequeathed a great deal of property to her children, grand-children, and her many friends. She also purchased a strip of ground on the west side of 13th Street, north of Market Street, with instructions to her executors to erect upon the property a "good brick church with eleven glazed windows, galleries, pew and pulpit, for the use of any congregation of worshipers belonging to the Reformed Synod."

Margaret's church, which came to be known as the Scots Presbyterian Church, was completed and opened on November 26, 1815. Her grandson, Rev. John M. Duncan of Baltimore, preached the first sermon. The first regular pastor was Rev. Thomas McNines, who served from 1822 to 1824. After 1824 the church was known as the Ninth Presbyterian Church. Eventually, after the church fell into disuse, the congregation was merged with the Second United Presbyterian Church on Race Street.

|

| Bainbridge Green, site of Margaret Duncan's Burying Ground |

An Unfortunate Fate and an Unsolved Mystery

Unfortunately, Margaret had forgotten one very important thing when making out her will-- to set aside funds providing for the upkeep of the church's burial grounds. The church's graveyard on Bainbridge Street, which had formerly been a potter's field for the poor of Southwark prior to 1800, saw its last interment in 1850. Within a few years, the area-- once the most affluent suburb of Philadelphia-- would become one of the city's filthiest and most neglected slums.

In February of 1892, local residents noticed that workers had begun digging up the graves at Margaret Duncan's Burying Ground. Although it was later revealed that the decision to remove the graves had been made by the Duncans' heirs in Baltimore, nobody seems to know why. And nobody seems to know where these human remains were reburied... if they were even reburied at all.

It is likely that Isaac and Margaret's descendents, who still held the deed to the property, "sold out" to developers during the Philadelphia building boom of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Perhaps the remains of Isaac and Margaret were laid to rest in another local graveyard, or buried in a family plot near Baltimore. But what became of the dozens of others who were buried there in unmarked pauper's graves?

Today, the parcel of land where Margaret Duncan's Burying Ground once stood is home to an urban park known as Bainbridge Green. Just one block south of the iconic Theatre of the Living Arts, the site is a welcome oasis for pedestrians and tourists seeking a shady place to sit on a hot summer day.

Comments

Post a Comment