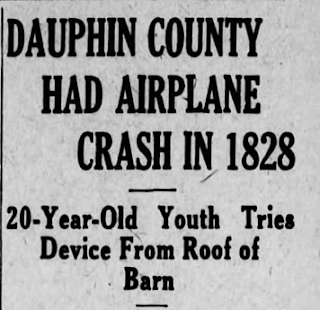

George Pletz: The First Casualty of American Aviation

Seventy-five years before the Wright Brothers flew into the history books, a pair of eccentric brothers from Dauphin County believed they had invented the world's first flying machine. And had the Pletz brothers attempted to make their maiden voyage on the sandy beaches of North Carolina instead of attempting to fly over Blue Mountain, Orville and Wilbur Wright might never have left their bicycle shop in Dayton.

The Blue Mountain Parkway, which connects Linglestown with Fishing Creek valley, was once known as Pletz's Pass, in honor of the John Pletz, an early settler to the region. Although details are scarce, it is known that John, who was born in 1785, was a carpenter by trade. It was only natural that John and Barbara's five sons-- John, George, William, Samuel and Benjamin-- developed an interest in woodworking.

It was sometime in the 1820s when George and his brother, John, Jr., came up with the idea of building a flying machine. Perhaps as children they had heard tales of Baron Stiegel's mythical glass airship which had, according to Pennsylvania legend, crashed into "The Pinnacles" of Blue Mountain in 1774. Although historical records describe twenty-year-old George as being "mentally subnormal", he convinced his brothers to help him, and they went to work designing a wooden flying machine, undaunted by the jeers and ridicule of their neighbors. After many adjustments and revisions, they hit upon a design they believed would allow them to soar as high as eagles.

Upon completion of the flying machine in early fall of 1828, George and John decided to test their contraption by flying it from Pletz's Pass to Piketown to visit their uncle, who lived on the east side of the mountain in Heckert Gap. On September 17, George and John launched their machine from the roof their barn with themselves inside. History fails to describe just how far the contraption flew, or if it even flew at all, but records show that the flying machine crashed and George died from a broken neck. He was buried at the historic Wenrich's Church Cemetery in Linglestown. As for his brother John, he suffered a broken arm.

|

| George Pletz's gravemarker at Wenrich Cemetery, Linglestown |

Outside of Linglestown this ignominious but historic debacle received little public attention and was largely forgotten until Nevin W. Moyer, a faculty member of Lower Paxton Vocational High School, discovered documents about the incident while compiling a book on the history of Wenrich's Church, which he distributed to friends and family as a Christmas present in 1922. Moyer, who had been interested in local history since all his life, had begun collecting records and newspaper clippings since he was a child, as well as the recollections of "old-timers" who lived in the area. While some of these old-timers vaguely recalled the incident, as they had heard it from their fathers and grandfathers, their recollection of the details were hazy at best (by this time, the ill-fated flight of the Pletz brothers was already ninety-four years in the past).

|

| Nevin W. Moyer |

Moyer's claims were corroborated in 1930, when the State Library in Harrisburg received baptismal, communion and burial records from Wenrich's Church, including records pertaining to the life and death of George Pletz. However, according to these documents, the unfortunate flight took off from a point closer to Hummelstown, not Linglestown, though this is probably in error. An 1873 atlas shows the homestead of John Pletz in West Hanover Township in Fishing Creek Valley (about two miles east of Pletz's Pass), but it is unclear if the John Pletz in question is the father or the son (John Pletz, Sr., passed away in 1874 at the age of 89. He is also buried at Wenrich's Church Cemetery in Linglestown). As for George's brothers, they all eventually moved to Springfield, Illinois.

Although many of the details as to from where the flight originated or where it crashed are murky, the story of the Pletz brothers was famous enough to inspire a local legend stating that the Pletz family was a blood relative of Susan Koerner, mother of Wilbur and Orville Wright (this is not true).

The legend of the Pletz brothers also warranted calls for the erection of monuments honoring George and John, Jr. as the true fathers of American aviation. Shortly before his death in 1930, Bishop James Henry Darlington, the first Episcopal bishop of Harrisburg, started a campaign to have a bronze marker erected at Pletz's Pass paying tribute to the pioneer flyers.

|

| Bishop James H. Darlington |

As every hiker, backpacker and outdoors enthusiast in Pennsylvania surely knows, Bishop Darlington played an important role in the evolution of the Appalachian Trail, which runs across Blue Mountain. The bishop was the long-time secretary and one of the early members of the Pennsylvania Alpine Club (of which Col. Henry W. Shoemaker, whose name is often mentioned on this blog, later became president). In 1908 the trail across the summit of Blue Mountain was named in Darlington's honor by the Alpine Club, and the Appalachian Trail later used a stretch of the Darlington Trail in its right-of-way before the Appalachian Trail was relocated to its present location. When Bishop Darlington passed away in 1930, the Alpine Club decided to erect a marker on Blue Mountain, but it was erected in the memory of the bishop. In July of 1936, the Harrisburg Evening News reported that a marker dedicated to the brothers would be erected at Pletz's Pass by the Paxton Rangers Hiking Club of Linglestown; however, it is not known if this plan ever came to fruition (if it did, I could find no record of it).

It is also interesting to note that Col. Shoemaker, the most famous of Pennsylvania's folklorists (who often stretched historical fact to the point of incredulity), often told the tale of the Pletz brothers in his newspaper columns for the Altoona Tribune. In one of Shoemaker's more colorful accounts, published in 1937, he placed the date of the fateful flight on Christmas morning of 1828, and described the flying machine as a brightly-painted contraption with an elaborate carving of Belsnickel-- the German version of Santa Claus-- mounted to the front as a figurehead. "The wings were decorated with sprigs of holly and mistletoe from the Blue Mountains, while the swarthy black-haired young airman wore a sprig of mountain ash in his coat lapel," wrote Shoemaker.

The story of the Pletz brothers has evolved since 1828, only to be forgotten and resurrected every few decades, with each re-telling containing new embellishments. And while the details may have been lost to history, the fact remains that the first attempt at flying a heavier-than-air aircraft in the United States took place near Linglestown in Dauphin County.

"History fails to describe just how far the contraption flew, or if it even flew at all,..."

ReplyDeleteHaving seen footage of other inventors using the roof of a barn as a launch pad, I think that the plane dropped straight to the ground like a stone.