Mickey Smith, the Peg-Legged Killer of Cambria County

|

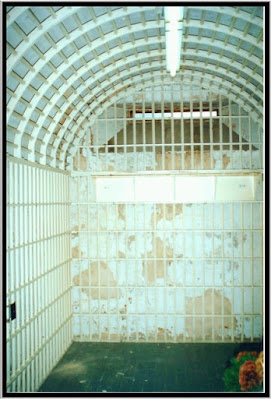

| The Old Cambria County Jail |

In the spring of 1884, a most peculiar series of murder trials took place in Cambria County. Two men, both of whom were named Mickey, were convicted of murder in the same week. Both men not only shared the same first name, but also the same handicap-- they both had wooden legs. But what makes this bit of historical trivia even more interesting is that both judges in these respective murder trials, Judge Dean and Judge Johnston, were also peg-legged. The court clerk who made out the juror's orders also had a wooden leg, as did the county treasurer who cashed the orders. One of the witnesses was peg-legged, while one of the jurors had not one, but two wooden legs. In total, there were nine artificial limbs in the Cambia County Courthouse during a single week in March of 1884.

Or course, there were millions of Americans hobbling around on peg legs in those days; after all, Cambria County had sent scores of men and boys to fight the rebels just two decades earlier, and this peculiar murder trial occurred at a time when most western Pennsylvania towns boasted steel mills, coke furnaces, rail yards, mines and factories where one could easily lose a limb in the blink of an eye. Actually, if you stop to think about it, it's quite miraculous anyone made it through life in those days with all their body parts intact.

But it is one of these two convicted murderers, Mickey Smith, who went on to achieve infamy after pulling off a daring escape from the Cambria County Jail in Ebensburg. This escape led to a massive manhunt and a spate of Mickey Smith sightings all across the state for years to come. And, strangely, no one knows for sure what became of the peg-legged escape artist. He was never caught.

From Constable to Killer

It was the night of August 26, 1883, when an altercation broke out at a tavern in Johnstown. The two drunken belligerents were John Minahan, a married father of three, and Michael "Mickey" Smith, an off-duty constable employed by the Cambria Iron Company. In attempting to arrest Minahan, Smith drew his revolver and fired. The ball struck Minahan in the right eye and penetrated the brain. Minahan, who was still alive, was rushed to the hospital, but died a few days later. Mickey Smith was arrested and confessed to the crime, blaming his actions on strong liquor.

Minahan and Smith had been feuding for years, and the source of their anger was neither money nor a woman, but a deer. The two men had been hunting buddies once upon a time but neither could agree on who had fired the shot that had brought down the trophy buck. While this event led to the dissolution of their friendship, the two men continued to frequent Halloran's Saloon, where they often engaged in heated disagreements over everything from politics to baseball.

On the night in question, an otherwise routine argument got a little heated and Mickey Smith threatened to arrest his former friend. Minahan, in no uncertain terms, told Smith to go jump in a lake. Smith then went outside to flag down a policeman, Officer Kelly, claiming that Minahan was drunk and disorderly. Officer Kelly, however, had no desire to get involved. Smith returned to Halloran's Saloon and pointed his gun at Minahan, intent on dragging him down to the police station. "Minahan grabbed at the weapon twice, then Smith stepped to one side and shot him," recalled John New, one of the witnesses. "He dropped like a log."

Mickey Smith, who was not only a lawman but a father of seven, turned himself in, believing that he would be saved by the sympathy of the jury. Not only was he well-liked around town, but he was also crippled and caring for a sickly, elderly mother. As the sole provider for his large family, Smith was confident that he would be given a lenient sentence. One can only imagine his surprise when, on March 6, a jury found the peg-legged constable guilty of murder in the first degree after a trial that lasted just three hours. And how surprised Mickey Smith must have been when Judge Dean sentenced him to hang.

A Daring Escape

The governor had fixed the date of Smith's execution for September 23, and as the months went by Mickey Smith firmly made up his mind that he had no intention of paying for his crime on the gallows. He realized that, in order to escape, he would need some outside help, and so he turned to his large network of friends to spring him from the state-of-the-art $120,000 jail.

One of the inmates, a career ruffian named Henry Goughnour, later recalled what he witnessed on the night of August 30, 1884:

"My cell was the fourth from the entrance on the left-hand side of the corridor. About 10:30 o'clock Saturday night I was lying on my bunk reading a novel, when I heard a sharp report, like the crack of a gun. I jumped up and blew out the candle and went to the iron door. I saw a mann pass the door, going toward the big iron doors at the entrance of the corridor, and while I stood there I heard him shake the doors and call out, 'Ho! Bert!' I didn't hear any answer, but I heard someone playing a fiddle in the front part of the jail.

"After shaking the big gates the person passed back close to my cell and went toward the heater. He was in his bare or stocking feet. I could not hear the thump of a peg leg, though. He was bareheaded. A friend of mine told me he was going to skip the jail, as he knew how, and I thought it was him, and as he passed the door I waved my hand at him and said 'Whist!' and he passed on. I didn't hear anything more for about ten minutes. Then I heard a rattling at the big gates outside, at the wall."

Goughnour admitted that night watchman James Myers hadn't been on duty that evening as he should have been, and stated that Smith's absence was not discovered until five o'clock the following morning, when another inmate, Elwood Gordon, happened to look out his cell window and observed that the prison gates were open.

According to Goughnour's statement, the escapee had talked to a man named "Bert" several times that evening. "About ten of fifteen minutes before I saw the man pass my cell, someone was up on the second tier, where Smith was kept," said Goughnour. "I head Mickey say, 'Bert, if you didn't get that paper, you need not mind it."

The Bert in question could only be Bert Luther, one of the guards, who was also a well-known fiddle player and the son of the local sheriff. Did Sheriff D.A. Luther, along with his son, aid and abet a convicted killer in escaping from the Cambria County Jail?

If so, Sheriff Luther quickly attempted to cover his tracks. The morning after the escape, Sheriff Luther sent an urgent telegram to Chief of Police Kinch, offering a large reward for Smith's capture. The telegram read:

Mickey Smith, convicted and sentenced for murder, escaped from the Cambria County Jail last night. $300 reward offered for his arrest. Smith is about five feet, ten inches tall, heavy set, having the right leg amputated below the knee and walks with a peg leg. He walks well and stands erect in walking. Has dark hair turning gray, and cut close. He has no beard unless about a week's growth.

William Minahan, a brother of the murdered man, arrived in Ebensburg the next day and met with the sheriff, who told him that Smith had somehow gained access to the jail's cellar before sawing off the locks from three doors. The lock on the front door of the jail had not been tampered with, however. The sheriff could offer no explanation as to how a peg-legged inmate left the jail without busting the lock on the main door, and could not provide an explanation for the disappearance of the night watchman, James Myers. Some reporters speculated that Mickey Smith might have gone over the wall, pointing out that, at the time of the escape, a ladder had been left outside the prison wall by workmen who had been repairing the roof. There were also hoofprints and a wagon track visible on the ground, leading in the direction of Carrolltown, and a witness claimed that he had seen a horse and buggy speeding past the Reed farm around one o'clock in the morning, about eight miles from Ebensburg. According to this witness, there were two men in the buggy, and the buggy was later seen passing through Belsano two hours later.

|

| A cell inside the Cambria County Jail (photo by Bill Badzo) |

The breakout of Mickey Smith and the accusations of negligence-- or outright corruption-- against Sheriff Luther and his brother gave Cambria County quite a black eye, and county commissioners were quick to offer an additional $1,000 reward for Smith's capture, dead or alive.

Meanwhile, professional and amateur detectives alike, enticed by the large reward, were doing their best to hunt down the fugitive. When the escapee's wife boarded a train to Pittsburgh on September 9 with an unknown woman and child, one detective jumped on board just as the train was leaving the station. Other detectives knocked on doors in Ebensburg, Johnstown and Altoona, desperate to find a clue to Smith's whereabouts. When Smith was reportedly spotted at the home of his father-in-law in Taylor Township, hundreds of "weekend warrior" bounty hunters descended upon the vicinity, but found no proof the fugitive had been there. In late September, a one-legged man was arrested in Lancaster, but was released after he was able to prove that he wasn't Mickey Smith. A one-legged Irishman was also arrested in Somerset County and released. Authorities back in Cambria County, however, assured the public that Mickey Smith would be caught before long.

One man who was also confident that Smith would soon be captured was J.D. Parrish, the man in charge of constructing the gallows. Parrish continued to erect the scaffold in the jail yard, unphased by the disappearance of the peg-legged convict. This was the fourth time Parrish had been called upon to erect such a contrivance; he had built the scaffold used to hang Daniel Buser and John Howser in April of 1866, and had assisted in the construction of the scaffold used in the execution of Michael Moore in November of 1872. Yet, some county residents were growing impatient. In the village of Cooperdale, residents hanged a dummy of Mickey Smith in effigy from a telegraph wire. Their lust for vengeance was somewhat satiated on September 24, when the other peg-legged killer, Mickey Murray, was hanged for the shooting death of young farmer John Hancuff.

The following month, another former inmate, George Kurtz, came forward and claimed that he had witnessed Smith's mother visiting the jail shortly before her son's escape, and that he had seen her pay Bert Luther a large sum of money in the corridor outside his cell. When four more inmates escaped in November under Bert Luther's less-than-watchful eye, some locals pointed to this as proof that Mickey Smith had engineered his escape with inside help. The fact that these four convicts had beaten Luther, stolen his keys, and locked him inside one of the cells did little to change this opinion. As a result of this fiasco, the disgraced turnkey was forced to resign. The December 12, 1884 edition of the Altoona Times reported that Luther was seeking employment as a carpenter, but was willing to accept "any other work that offers". Although no proof was ever found that Bert's father had played a role in Mickey Smith's escape, his reputation was also sullied beyond repair; after losing re-election to Joseph Gray in 1886, Luther and his wife moved to Carroll Township, where the ex-sheriff took up farming.

Cambria County Gives Up Hope

In February of the following year, the Cambria County commissioners withdrew their reward, stating their belief that Mickey Smith would never be recaptured, unless he were to grow bold enough to return to the area. Some newspaper editors breathed a sigh of relief, such as the editor of the Indiana Democrat, who wrote: "The arrest of peg-legs throughout the country will doubtless now cease, and unfortunate cripples can hobble about... without fear at every turn of being taken up on suspicion of being Cambria County's missing Mickey."

As it turned out, the arrest of peg-legs throughout the country did not cease-- at least not for several more years. In February of 1885, police in Danville, Illinois, arrested a man they believed was the infamous "Missing Mickey". Similar arrests were made in Ohio, Georgia and North Carolina.

Authorities grew optimistic in May, when Smith's three-year-old son passed away. Detectives were on hand at the boy's funeral in Johnstown, but the fugitive failed to make an appearance. He also failed to materialize in 1887, when newspapers across Pennsylvania reported that his wife had taken a new husband, or in 1890, when his mother passed away.

Where's Mickey?

In the days before the automobile and the telephone, hundreds of prisoners escaped each and every year. Most were eventually re-captured and some went out in a blaze of gunfire. Many were never heard from or seen again and faded from memory. But the case of Mickey Smith is unusual because he was still fodder for gossip mills into the dawn of the 20th century. Whenever a rumor circulated about Mickey's whereabouts, no matter how ludicrous or unfounded, papers were quick to print it. As it turned out, the peg-legged fugitive had become something of a folk hero.

For instance, in January of 1888-- nearly four years after he shot and killed John Minahan in Halloran's Tavern-- one local paper published a story reporting that Mickey Smith had escaped to the Pacific Northwest and had evaded authorities after his escape by hiding out in a cave near Ebensburg for nine months. In September of 1895, a man from Westmoreland County named Nelson Pyle wrote a letter to the Cambria County prothonotary asking if the reward for Smith's capture was still being offered. After being informed that the offer had been rescinded more than a decade earlier, Pyle wasn't heard from again.

The last time Mickey Smith made headlines was in the summer of 1898, when authorities in Allentown reported they had a man in custody who might be the missing convict. The fact that the identity of the man in question had been verified by former Johnstown residents aroused a fair amount of interest, until it was later determined to be yet another case of mistaken identity.

So whatever happened to the one-legged constable who shot and killed his former hunting buddy during a barroom argument in 1883? Did he finally run afoul of the law in some sparsely-populated Western town and pay for his crimes on some crude scaffold atop a sagebrush-dotted hill? Or did he live out the remainder of his life in obscurity, constantly looking over his shoulder, yet smug in the satisfaction that he pulled off one of the greatest jailbreaks in Pennsylvania history?

Sources:

Indiana Democrat, August 30, 1883.

Philadelphia Times, March 7, 1884.

Lebanon Daily news, March 7, 1884.

Indiana Democrat, March 20, 1884.

Altoona Times, Sept. 10, 1884.

Altoona Tribune, Sept. 11, 1884.

Altoona Times, Sept. 20, 1884.

Philadelphia Times, Oct. 15, 1884.

Altoona Times, Nov. 13, 1884.

Indiana Democrat, Feb. 5, 1885.

Cambria Freeman, Feb. 13, 1885.

Cambria Freeman, Jan. 8, 1886.

Connellsville Weekly Courier, Jan. 13, 1888.

Cambria Freeman, Sept. 13, 1895.

Altoona Times, July 8, 1898.

Comments

Post a Comment