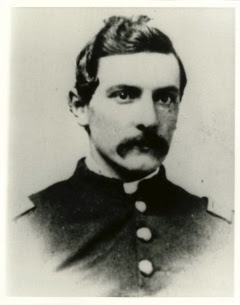

Jacob Haas: John Wilkes Booth's Coal Region Doppelganger

|

| Capt. Jacob Washington Haas |

The greatest manhunt in United States history took place in April of 1865 to catch the assassin of Abraham Lincoln. Within a few hours after the President's murder in Washington D.C.'s Ford's Theater, Federal authorities knew the identity of the killer --- the celebrated actor, John Wilkes Booth.

Booth remained at large for twelve days before he was trapped in a barn near Port Republic, Virginia. Whether he ended his life with a pistol shot after discovering that the barn was surrounded, or died from a sharpshooter's bullet, remains an unsettled question. But few people were more relieved to learn of Booth's demise than Captain Jacob Washington Haas, a Pottsville native who served during the war as commander of Company G, 96th Regiment. The reason for Jacob Haas' relief was simple: Haas had the uncanny misfortune of being the spitting image of the notorious presidential assassin.

But what makes the life of Captain Haas even more remarkable is that, on three separate occasions, he narrowly escaped from the hands of angry mobs who sought to lynch him for the greatest crime in American history.

Haas was a 28-year-old father of three when he went off to war in 1861. As a member of the 96th Regiment, which was composed of Schuylkill County volunteers, Haas saw plenty of action, and was nearly killed during the a skirmish at Salem Church during the 1863 Chancellorsville campaign. “We were advancing and were within 15 passes of their Rifle Pit when I was struck on the side of my head by a ball which glanced upwards through my cap, knocking me down and stunning me,” Haas wrote in his journal. Jacob's three brothers, who lived in Shamokin, also fought with the Union. One brother, James, was killed at the Battle of Cedar Creek in the Shenandoah Valley in the fall of 1864.

Six months after being mustered out of service, just a few days after Lincoln's death, Jacob Haas left Pottsville with his former regimental commander, Coloner William Lessig. The men had their sights set on the newly-opened oil fields of Western Pennsylvania, where they hoped to make a fortune. As luck would have it, they hardly made it past the Susquehanna River. After the two men sought lodging for the night at a hotel in Lewisburg, a number of local residents became convinced that Haas was the infamous fugitive, and as the men sat down to dinner they were accosted by several men with drawn pistols. In the ensuing melee, Haas and Lessig had to barricade themselves inside their hotel room for several hours until an acquaintance from Sunbury could vouch for Haas' identity.

|

| John Wilkes Booth |

Hass and Lessig continued on their journey, only to be apprehended near Philipsburg by a detail from the 16th Pennsylvania Cavalry who had been taking part in the nationwide manhunt for Lincoln's killer. This ultimately turned out to be a fortuitous turn of events for the Pottsville veterans; it was the cavalry who kept Haas and his companion from being hanged by a group of vigilantes who were certain they had located John Wilkes Booth.

"We were taken to Phillipsburg and a great crowd soon gathered, learning that the slayer of Lincoln had been caught," Haas wrote. "Cries of ‘shoot him, lynch him’ were heard and I felt chills when several ruffians produced coils of rope."

The men were set free after Colonel Lessig provided evidence to the lieutenant in charge of the detail that they had served in the 96th Regiment. The lieutenant, G.P. McDougall, issued the travelers a safe conduct pass, upon which he had written:

I have this day arrested W.H. Lessig and J.W. Haws [sic], and examined them and find they are not, as suspected, Booth, the assassin of President Lincoln.

Haas and Lessig continued on their way, only to be apprehended once again by an angry mob near Clarion. This time it appeared that not even the lieutenant's safe conduct pass would save their necks; after the posse produced a noose, it looked like it was the end of the line-- until the men made a desperate plea to be taken to Franklin, where they claimed to have accounts in a local bank. The cashier at the Franklin bank was able to establish their true identities and Haas and Lessig were set free-- just as word spread throughout the country that John Wilkes Booth had died in Virginia.

Jacob Haas never struck it rich in the Western Pennsylvania oil fields, but it's safe to say that he had more than enough adventures to last a lifetime. He eventually moved to Shamokin and found employment as a mine superintendent. He remained in Shamokin until his death on June 24, 1914, at the age of 81.

Comments

Post a Comment