The Girty's Cave Mystery Corpse

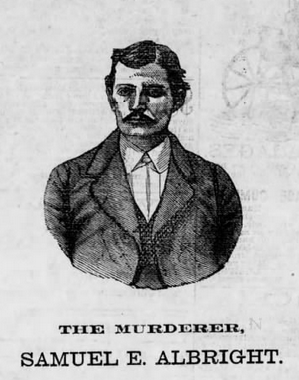

If you were to ask history buffs around Perry County about the most famous mystery in this region, most of them would answer without hesitation that it was the 1879 discovery of a badly-decomposed corpse inside a cave that had once been the secret hiding place of Simon Girty, the famed outlaw, over a century earlier. The gruesome discovery was made in the wake of the murder of William K. Miller, who was shot in the home of his newlywed bride's sister by a jealous rival suitor named Samuel E. Albright, who fled into the wilderness of Girty's Notch and was never heard from again.

It was supposed that the corpse was that of Albright, who had taken his life with his revolver as hundreds scoured the woods and mountains in their quest to bring the young man to justice. Though Albright's relatives had positively identified the remains, which were hastily buried, it did not take long for some to claim that the body was that of a tramp or some other unfortunate stranger who had been murdered by Albright, dressed in the fugitive's clothing, and dragged into the cave in an attempt to throw pursuers off the killer's trail. To this day, heated debates still break out occasionally around Perry County over the true identity of the body found in Girty's Cave; there are strong arguments supporting both theories.

The Murder of William Miller

A half mile below Montgomery Ferry, on a farmstead owned by John Noviock, lived Henry Hammaker, whose sister, Maria, was romantically involved with a local outlaw named Samuel Albright. Throughout the 1870s, Albright's gang of bandits robbed the farmers of Bucks Valley and waylaid travelers at Montgomery Ferry with equal aplomb. In the spring of 1877 Albright's gang was implicated in the theft of a large quantity of smoked meat from the barn of Jacob Buck. Albright and his accomplices, E.K. Bitting and John Shaeffer, were arrested on a charge of larceny, and while Bitting and Shaeffer eventually convicted and sentenced to eighteen months and three years in the Eastern Penitentiary, respectively, Albright jumped bail and hid in Texas. During his absence, Maria Hammaker bore him a child, but when Samuel Albright finally reappeared in Perry County in May of 1879, he was astonished to discover that Maria had become the bride of William K. Miller, a railroad worker from Harrisburg.

In August of 1879, Albright learned that his former lover and her new husband were returning to Buffalo Township to visit Maria's sister. Albright, who had sworn revenge against Miller, was determined not to let this opportunity go to waste. On the morning of Thursday, August 7, Samuel Albright had encountered John Noviock outside the home of his father, Benjamin Albright, and offered to help Noviock thresh grain on the Hammaker farm. Noviock agreed, and the two men proceeded by wagon to the Hammaker home-- Albright with the secret intention of murdering both his former lover and her new husband.

Of this detail there is no doubt; Albright had brought along two crudely-written manifestos, one for Maria and one for the public, declaring his intention. He had just handed Maria one of the letters when he pulled out a revolver and shot William Miller three times. Miller died within seconds. The post mortem examination revealed that the first shot had entered Miller's chest between the second and third ribs and pierced the left lung and spleen; the second shot pierced both lungs and cut a furrow through the left ventricle of the heart; the third lead ball lodged itself in Miller's spine.

Albright then attempted to fire at Maria, but her sister knocked the gun away just in the nick of time, causing the shot to miss. He dropped the other letter on the ground as he fled the scene of the crime and disappeared into the mountains. The letter read:

To the citizens of the surrounding country, knowing that there will be quite an excitement and talk about this little fuss I take this plan to make things a little plain to you. In the first place, I think I am doing my duty. In the second place I am keeping (or saving) Maria from being followed around like a dam [sic] dog by this cuss which she could not keep away from her and in the third place do what every man should do-- protect what belongs to him. Concerning myself you all know about as well as I can tell you. Our relationship has spoke for itself long ere this. The binding part can be told by herself if she sees fit. The direction I take you must find out yourselves, but lead must meet any one who shall follow on my trail.

Respectfully,

S.E. Albrite

P.S.-- This hellion has been warned twice if he would come up here he would be killed. Dam [sic] a man that follows another's wife.

The letter which he had handed to Maria read:

As I told you from the first time you told me that imp was going to follow up from town I said he must be hurt if he comes. So now he has got it sure. Don't blame me but if any one why your own dear self and him also good by I will see you again love.

Maria you will remember now what I told you and all your fault. Never do a trick like that again good by till I see you again.

SAM

Albright was pursued by Noviock, who was outside threshing grain when the fatal shots had been fired, and Isaiah Silks. Both men were scared off by Albright's threat to shoot them, but other locals soon joined in the hunt. A posse was formed by Constable Sailor and the woods around Montgomery Ferry were searched until evening. Coroner Zinn proceeded to the Hammaker home and empaneled a jury, and a verdict was reached declaring that William K. Miller came to his death at the hands of Samuel E. Albright. Undertaker Lutz soon arrived from Liverpool and put the body on ice.

The following day word of Miller's death reached Harrisburg and the bell of the fire company of which he was a member was tolled in respect to his memory. Miller, who was 27 years of age, left behind two children born to his former wife, Bella Weeks, who had preceded him in death two years earlier: Harry, age five, and Cyrus, age four. County commissioners offered a $250 reward for Albright's capture, and photographs of the killer were distributed to detectives throughout the region.

The Lost Hours of Samuel Albright

Albright's actions during the following days are shrouded in mystery, but if the fugitive's actions were known for certain, the corpse that was later found in Girty's Cave could have been easily identified. There were many sightings of the killer in the days following the murder; on Sunday the killer was reportedly seen on Half Falls Mountain in the company of his father, a brother, and a man identified as Jesse Johnston (who was subsequently arrested for aiding and abetting Albright). Since few believed Albright would be foolish enough to linger in the vicinity of his home, this report was written off as "hogwash". Others reported seeing him in Marysville and Rockville during this time. The fact that the Albright clan was scattered all over Buffalo and Watts townships muddied the waters; Samuel himself had several brothers bearing similar physical characteristics. In effect, there were probably a half dozen young Albrights in that part of the county who could easily have been mistaken for the killer.

The strange behavior of Maria Hammaker also didn't help clear up any mysteries. At first she refused to tell Miller's mother the name of the minister who had married her to her son. After intense questioning she admitted that she and Miller were not married at all-- at least not in the legal sense. Rumor had it that Maria had been "keeping house" for Miller while Albright was in Texas, and the employer-employee relationship soon turned romantic. This seems to shed some light on the claim made by Albright that Maria was his "wife", though no record exists of any official marriage between the two. One local pastor did come forward, however, to state that Samuel and Maria had once asked him to marry them, but were turned away because they were both under the legal age at the time. What is known, however, is that while Samuel was hiding out in Texas, Maria bore him a child whom she immediately abandoned, leaving its upbringing to the killer's parents, Benjamin and Mary Albright.

Sympathy for the Devil

Some of Albright's friends held firm in their belief that the fugitive had fled to Texas once more to escape the long arm of the law. Other friends insisted that he may not have gone far at all; surprisingly, public sentiment over the affair was equally divided and Albright had his share of sympathizers, many of whom would have no qualms about hiding him. These rural and lawless mountainfolk living on Half Falls Mountain were deprecatingly referred to as "Snake-feeders" by other Perry Countians because they had long provided food and shelter for Albright's gang and other ruffians.

On Wednesday, August 13, an interesting incident occurred across the river in the borough of Dauphin, when a man in ragged clothing stopped at the home of an elderly woman in order to borrow a needle and thread to patch up his torn clothing. According to the woman, the man looked as if he had been rambling through the wilderness. He then hired the woman's sons to ferry him across the Susquehanna, which they did. Upon reaching the Perry County side, however, the man ran off into the mountains without paying. The two boatmen claim that their passenger had no mustache, but had a cut above his lip which seemed to suggest he might've recently shaved.

By this time all of central Pennsylvania was on the lookout for Samuel Albright. The Harrisburg Daily Independent boasted that it had secured the exclusive rights to publish etchings of the killer made from a family photograph, and sales of the August 14 edition, in which Albright's likeness appeared, were so brisk that the paper's steam presses nearly overheated from the demand for extra copies (thereby demonstrating what the phrase "hot off the presses" means). As the weekend drew to a close, the sheriff's posse returned to Newport, worn and ragged from combing the mountains. They had followed Albright's trail to the barn of a farmer near Sherman's Dale, where Albright had allegedly spent Wednesday night after being turned away by a hotel proprietor, but the killer was long gone by this time. Some sources claimed to have heard this would-be lodger say that he was headed to Cumberland, Maryland, where one of Samuel's brothers was working on the canal.

|

| Simon Girty |

The Cave of Simon Girty

In 1730, Simon Garrity left Ireland and settled along the Susquehanna River at a spot known to the local Native Americans as Paxtang, where a trading post was operated by an Englishman named John Harris, the founder of Pennsylvania's capital city. The few white settlers in the region called him "Girty", the Anglicized version of the name, and Simon Garrity eventually married Mary Newton, who, in 1741, gave birth to Simon Girty. They settled illegally near the mouth of Sherman's Creek, in defiance of British authorities, who responded by burning their cabin to the ground.

Not long after, Simon Girty the Elder was killed in a duel by a rival trader. Mary Girty married John Turner three years later, but the marriage was short-lived; Turner was burned at the stake by the Munsee band of the Lenape after a scalping and three hours of barbaric torture. The Girty children were kidnapped by the Indians and split up, with fifteen-year-old Simon being "adopted" by a Seneca chief named Guyasuta. As an adult, Simon Girty fought for both the British and the Colonial armies at various points in his military career, earning him a reputation as both a hero and a traitor, depending upon which side he was on at the time. But Girty's only true loyalty was to himself; during his time in Perry County he was a greatly-feared bandit, using the tactics he had learned as a Seneca to ambush and rob travelers along the Susquehanna Trail and hiding his loot in a small cave near the top of Half Fall Mountain, in a spot that has come to be known as Girty's Notch.

It was near this infamous spot where Augustus Liddick and Michael Shatto detected a putrid stench on the afternoon of August 18, 1879 as they were walking along the highway. They followed the stench to the outer apartment of the cave, where they found a badly-decomposed body. A crowd soon arrived at Girty's Notch and the personal effects of the dead man were identified as the pipe and knife which had belonged to Samuel Albright. As for the revolver, it was identified as the gun which Albright had borrowed from Maria's brother, Adam Hammaker.

Unfortunately, the advanced state of decomposition had rendered the corpse's features unrecognizable; the head detached itself from the spine during the removal of the remains from the cave, and the arm bones pulled out of their sockets. In fact, the color of the skin was so blue that Shatto and Liddick initially believed the body was that of an African-American. Justice of the Peace A.E. Howe viewed the remains at the scene and pronounced them to be those of Albright. Death was apparently caused by a single gunshot wound to the center of the forehead.

And, from this point on, things get very strange.

The Mystery of the Corpse

Although it was evident that the corpse was attired in Albright's clothing and suspenders, and that the revolver found in the cave was the same one which had been used to murder William Miller, not one person could positively identify the actual body with any degree of certainty. Nonetheless, one of Albright's brothers and a sister hastily pronounced that the remains were indeed those of Samuel, and they promptly sent for undertaker Westly Miller of New Buffalo, who placed the decomposing corpse in a hearse and transported it to the Albright home in Buck's Valley for a swift burial. Upon hearing this, District Attorney Wallis decided to pay a visit to the Albright residence at once for the purpose of holding an inquest before the body could be buried.

Within hours of the discovery, allegations of a cover-up were rampant. Not only was Augustus Liddick the first person to discover the body, but he also happened to be the last person who was known to have seen Samuel Albright alive. People living in the vicinity of the cave had first observed a foul smell in the air on Tuesday, August 12; yet Liddick was seen with Albright by multiple witnesses on Wednesday, August 13, in Watts Township. Michael Shatto, who was with Liddick when the body was found, was also a close friend of Albright and had been in his company the day before the murder was committed.

Of course, this could've been a series of mere coincidences. Based on the degree of decomposition and weather conditions, many declared that Albright must've gone to the cave with the intention of suicide immediately after fleeing the Hammaker home. The wave of Samuel Albright sightings simply could've been cases of mistaken identity; after all, virtually everyone in and around Buck's Valley was related to the Albrights either by blood or by marriage. It stands to reason that many of them shared similar physical traits. This possibility was raised at the time by a respectable resident of Watts Township, who pointed out that Samuel and his brother Albert bore a strong resemblance to each other. Besides, if Albright had murdered a tramp or stolen a fresh corpse to substitute as his corpse, there should've been reports of a missing person or a desecrated grave. But there weren't.

The Resurrection of Samuel Albright

The only corpse that was exhumed was that of the man found in Girty's Cave. District Attorney Wallis and Coroner Zinn arrived too late; they reached Hill Church Cemetery in New Buffalo just as the funeral was nearing its completion. Wallis ordered the grave to be opened immediately, and a gruesome spectacle ensued after the coffin lid was removed. A correspondent from the Harrisburg Telegraph reported:

Instead of the body lying in a proper position, the head was off and lay under the left arm and the entire body was a mass of putrefication, even falling to pieces... Could a body decompose in eleven days so rapidly as to fall to pieces? Drs. Orvis and Eby, who examined the body, disagree in their opinion.

The Telegraph correspondent also pointed out one curious detail which, if true, would have exploded the Albright family's claim: Samuel Albright was said to have lost one of his fingers, yet the corpse found in the cave had all ten fingers intact (though the correspondent failed to state whether or not he had actually seen the body at Girty's Cave). The bullet hole in the center of the forehead also raised some suspicion. Wouldn't a suicide victim normally shoot himself in the temple? And the location of the cave, approximately 150 feet above the Susquehanna Trail, also presents a curious detail. How could Shatto and Liddick detect the odor produced by organic gases from such a low altitude? Putrefication produces methane, hydrogen sulfide and ammonia, all of which are lighter than air. These vapors would've wafted upwards into the atmosphere, not down the hillside.

Strangely, there is one possible explanation for identity of the mystery corpse of Girty's Cave. On August 14, just four days before the body was found by Shatto and Liddick, a fisherman at Cove, Perry County (about ten miles downriver from Montgomery Ferry) spotted a partly-decayed body bobbing in the water, presumably that of a suicide or drowning victim. He raced to fetch Squire Nathan Vanfossen, but when they returned, the body was nowhere to be seen. The Duncannon Record reported:

A jury was summoned, a box got ready by the undertaker and all hands started for the dead man. But somehow or other when the party reached the place the dead man had disappeared. What had become of him was a mystery. The gentleman reporting the matter is a perfect temperance man and of course never troubled with the "jim jams" or anything of the kind. The box was brought home empty, and the gentlemen looked as if they would rather not be questioned about the matter.

It's a well established fact that the decomposition of a corpse occurs more rapidly once the body of a drowning victim has been brought ashore than if it had remained in the water, and four days would've been more than sufficient to turn a partly-decayed corpse into the mass of putrefication which was pulled from Girty's Cave. And while countless articles have been written about the case, all of them seem to overlook one very important and potentially damning clue: Shatto and Liddick claimed they first thought the body inside the cave was that of a black man because of the skin discoloration. Cyanosis-- a condition in which the skin turns blue-- is consistent with death by drowning.

While these facts seem to suggest that Albright faked his own death, the second inquest-- the one conducted after the coffin had been dug up-- kept alive the theory that Samuel Albright had taken his own life after murdering William K. Miller. The inquest began that evening at Hill Church, but nightfall forced District Attorney Wallis to continue the inquest in Newport the following morning. Dr. Eby testified that a bottle of laudanum was found in the dead man's pocket, and Albright's mother had been missing a bottle. Dr. Eby also found a scar on the dead man's knee which matched a scar which had also been on Albright's knee. And as for the "missing finger", the extent of this injury had been greatly exaggerated; Albright, whose left hand had been injured in a farming accident, never completely lost the appendage-- just the tip. Because of the advanced decomposition, it was impossible to tell if the corpse was missing a fingertip. Some claim that it was, others claim the corpse had all ten digits. Unfortunately, because the inquest was moved out of town, several key witnesses failed to show up to offer testimony.

|

| Albright's grave at Hill Church Cemetery (photo by Scott Shatto) |

Jesse Johnston, the man who was reportedly seen on Half Fall Mountain with the murderer and arrested, was released from custody by Judge Junkin after the sighting had been ruled a case of mistaken identity (it was Albright's lookalike brother whom the witness had seen that day), and there was was no shred of evidence proving that Albright had been seen after shooting Miller. During the inquest, even one of the Liddick children testified that he couldn't tell Samuel and Albert Albright apart. A hair sample taken from the corpse also matched the color of Albright's hair, which means that the odds of a drowning victim with the exact same haircolor and the same scar on his knee washing up on the riverbank at the exact same time Albright was missing have got to be pretty astronomical. After all, the only person who had seen the floating corpse (or claimed to have seen it) was a fisherman who would not give his name to the newspaper.

The possibility of taking another body of the same physical stature as Samuel Albright and dressing it up in Albright's clothing in absolute secrecy in the midst of a massive manhunt is also dubious when one considers all the details the perpetrator would have to take into consideration; the dead man's outfit included shirt, pants, hat, suspenders, boots and stockings, all of which were identified as Albright's, and they all fit the dead man perfectly. What are the odds that all of these articles of clothing would fit a substitute corpse so snugly on the first try? And what are the odds that this corpse could be conveyed 150 feet up an almost perpendicular cliff and dragged into such a small cave (the entrance of which was reported to be just eighteen inches in height and two feet in width) in the heat of a countywide manhunt without attracting anyone's attention?

A Journey to Girty's Notch

Following the conclusion of the proceedings in Newport, the coroner's jury traveled to Girty's Notch to view the crime scene for themselves. They were led to the cave by David Lowe, which was now accessible by a well-worn path made by hundreds of curiosity seekers. It took the men considerable effort to crawl into the cave, but once inside they measured its length at thirty-two feet and its ceiling at ten feet. The body had been found about five feet past the entrance. The men found hair samples on the ground, but, oddly, no traces of blood. They returned to Newport that evening and met at Centennial Hall, where additional testimony was given by local physicians.

On Wednesday evening, August 20, the jury convened at Justice of the Peace Zinn's office and attempted to agree on a verdict. Five members refused to concede that the corpse was that of Samuel Albright, while only believed that it was. The coroner, refusing to accept a split verdict, announced that the jury would re-convene the following day. The coroner hoped that additional facts of the case might come to light in the meantime. No facts emerged, only wild rumors and speculation, and court eventually upheld the initial finding that the Girty's Cave corpse was that of Albright.

This delay caused an uproar throughout the county, however, and every newspaper editor was deluged with letters from those voicing their opinions. Many insisted that while the corpse had a scar on his knee, the only witness who testified that Albright had a similar scar was his own brother, and if his brother had aided Samuel in procuring a corpse, surely he would have examined it for any peculiar marks for the purpose of "identifying" the corpse later. Likewise, the witnesses who had identified Albright's clothing and personal effects were members of the killer's own family, or those "Snake-feeders" who sympathized with him. Others pointed to the bottle of laudanum found in the pocket of the corpse. If Mrs. Albright wished to shield her son, why wouldn't she claim that the bottle was hers? Why would Samuel decide to shoot himself while carrying poison? If the substitute corpse was the body found floating the in river-- presumed to be a suicide-- wouldn't it make more sense for this person to have a pocketful of laudanum?

Maria Hammaker, whose statements would've been invaluable, was laid up at the Harrisburg home of a family friend, Captain Albert Gallaton Cummings, due to "nervous prostration". Maria, of course, was not above suspicion. Some speculated that she and her former beau might have rekindled their romance when he returned from Texas, and that she could have lured Miller to Montgomery's Ferry in order for Albright to kill him, knowing that Albright had many allies in the vicinity who would shield him from capture. Though improbable, it was certainly possible. Miller was several years Maria's senior, and the pair had little in common. Perhaps Maria, believing that Albright would never return, consented to marry William Miller merely for the financial security such an arrangement afforded. Plus, there's also the fact that Albright had borrowed the murder weapon from Adam Hammaker. As one of the inquest witnesses later opined in a letter to the New Bloomfield Times: "I am not the only one that thinks Miller was brought here on purpose to be killed. If such was not the case, why did the girl bring him here at all, knowing, as she says she did, that Albright had threatened his life?"

As if the Albright name hadn't suffered enough damage, in late August the thirteen-year-old younger son Samuel Albright created a ruckus when he pulled a pistol on the young son of Fred Buck and took a shot at him. Fortunately, the shot missed, but neighbors claimed that the youth had been toting a pistol at his school every day since the previous winter.

On Monday, September 1, Perry County commissioners held a meeting and decided to increase the award amount for Albright's capture from $250 to $1,000, the consensus now being that the Girty's Cave corpse was not that of the murderer, though one of the commissioners later remarked, "It may as well have been made $20,000, for it will never be called for."

Howe Fires Back

A.E. Howe, the acting coroner who had been the first to examine the body after it had been pulled from the cave, published a lengthy rebuttal in the Harrisburg Daily Independent on September 13 attacking those who believed that Albright had faked his own death. To those who questioned the lack of blood found inside the cave, Howe pointed out that he had found Albright's blood-stained hat at the scene himself. If Albright had been wearing this hat when the fatal wound was inflicted, surely it would've absorbed the blood. In his letter, Howe asserted that the identification had been made partly through the corpse's teeth (though it had been another brother, Christian Albright, who recognized this feature), and scoffed at the notion that Albright had very many sympathizers in Watts and Buffalo townships:

All the sympathizers he has in both townships can be counted in one half dozen, and we doubt if any one of them could have been induced, out of pure sympathy, to have assisted him in putting a dead body in that cave and dressing it up in his clothes as a blind for him to escape behind.

This, of course, is far from the truth-- Albright had more than a half dozen siblings alone. Howe also contradicted himself when he lashed out at those who questioned the lawfulness of the local citizenry:

The raving of the Philadelphia Times correspondent from your place is, to say the least, brutish; when he holds all the citizens of Watts and Buffalo township up to public view as being in sympathy for the murder, we must believe him to be laboring under a temporary aberation of mind. For order-loving and law-abiding citizens, we will pit Watts and Buffalo townships against any other part of Perry County. The citizens of Buffalo township had Albright in the Quarter Sessions, and convicted him of larceny.

Albright, of course, was never convicted-- he jumped bail and fled to Texas before his court date. And, upon his return, he rollicked about his old stomping grounds with impunity. If the locals were so law-abiding, why didn't they turn him over to authorities? Why were Albright and his bandits allowed to terrorize the county for years? That's hardly what anyone could describe as a shining example of law and order.

Howe also declared that the "substitute corpse" theory was impossible because the body in the river spotted on August 14 had been recovered. This may or not be true; a body was recovered from the river on Sunday, September 7-- more than three weeks later-- but this body, which was recovered by Joseph Monmiller, was that of a 14-year-old boy. When it was found, it was missing its head, arms and upper torso. Neither the description nor the timeframe coincided with that of the original floating corpse. It appears that Howe was "grasping at straws", defending his reputation with half-lies and partial truths.

Alfred Potter's Claim and Maria Hammaker on Trial

On Monday morning, September 22, Maria Hammaker was arrested by Constable John Sailor, on a charge of perjury for declaring under oath at the inquest of William Miller on August 7 that she had been his wife. At a hearing before Alderman Maurer, Captain Cummings secured Maria's release by posting her bail in the amount of $300. Her court date was set for October. It was John Albright, a brother of the killer, who had gone to Newport and swore out an oath before Squire George Zinn charging Maria with perjury.

There is a very good reason why John Albright wanted to silence and discredit Maria, and anyone else involved in the mystery; in early September, a childhood friend of Samuel Albright swore out an affidavit claiming that he had seen the fugitive in Lycoming County. The statement made by Alfred Potter seemed to provide rock solid proof that Albright had staged his own suicide.

Twenty-two year old Alfred Potter declared to Justice of the Peace G. Cary Tharp under oath that on September 2, while working at the Muncy Hills Stone Quarry, Samuel E. Albright, accompanied by a teenage boy, had shown up in search of a job. Potter was working with a man named Fry who had lived near Montgomery's Ferry at one time, and when Potter saw the job-seekers, he exclaimed to Fry, "There comes Albright!" When Albright recognized Potter, his face turned pale and he appeared uneasy; he put his hand in his pocket and kept it there while Potter talked to him. Potter, who wasn't even aware of the murder, pressed Albright for several minutes about the happenings "back home", asking about old friends and acquaintances. Their conversation was interrupted by the dinner bell. By the time lunch was over, the two job-seekers had disappeared. In the affidavit, Potter declared:

I was well acquainted with Albright; he and I were raised in Buffalo Township... My grandfather (Jacob Bair) and Capt. Samuel Albright (grandfather of Samuel E. Albright), resided on adjoining farms, and Benjamin Albright (father of Samuel E. Albright), resided on a farm adjoining the Capt. Albright farm. One of my aunts is married to an uncle of Samuel E. Albright... I saw Albright frequently up to the time he was convicted for stealing Buck & Krumbler's meat and left the neighborhood. When Albright came to the quarry he had on a new suit of dark clothes. I recognized him by his voice, his light moustache, his peculiar teeth and his general appearance.

After Alfred Potter's statement was published, two of the killer's brothers, John and Alfred Albright, approached Alfred Potter's brother on the street of New Bloomfield and attempted to persuade him to convince Alfred to recant his statement. This inspired the Harrisburg Telegraph to ask, "If John and Alfred Albright are so certain that Sam is dead, why are they so anxious to stop any suspicion to the contrary?" A few days later, John Albright had Maria Hammaker arrested.

"It is more likely that the Albright boys fear Sam will get to some place of safety and send for the girl and she going to her lover will leave a trail which the detectives will follow," opined the Telegraph. "If this is not their fear, why should they have the unfortunate Hammaker girl arrested? But if Sam Albright is alive, isn't he safer from arrest by having the temptation to send for his sweetheart removed through her confinement in the penitentiary for a year or two under sentence for perjury?"

When the perjury case came before Judge Junkin on October 27, it was promptly dismissed. The judge ruled (however incorrectly) that perjury was defined as swearing falsely to a judicial oath, and that an oath administered by a coroner had no legal merit. The Pennsylvania Code, however (Article XII-B, Subarticle B, Section 1229-B) clearly states: The coroner may administer an oath and affirmation to an individual brought or appearing before the coroner. An individual swearing or affirming falsely on the examination commits perjury.

The Fate of Samuel Albright

The fervor surrounding the case had dwindled considerably by fall, even after the Albright family offered their own reward in October, in the amount of $2,000, to anyone who could prove that Samuel was alive. Though it was abundantly obvious the Albrights didn't have $2,000 to offer, they stated that they would never have to pay it-- they were convinced beyond any doubt that Samuel was dead.

Nevertheless, word of the occasional sighting of Samuel Albright occasionally reached Perry County. In January of 1880 Albright was reportedly seen in Leadville, Colorado, by James Wright, who was married to one of Albright's aunts. Later that year, he was allegedly seen in the Dakotas and southern California, where he was now living as a habitual drunkard, for which he blamed Maria Hammaker. An article on the Albright sighting from the December 6, 1880 edition of the Altoona Tribune, it was reported that Albright claimed to have said that, if he had to do it all over again, he would've killed Maria instead of William Miller. The following year the killer was reportedly spotted in Kansas, and was said to have been anxious to return home to Perry County. He was allegedly seen on Third Street in Harrisburg in January of 1882.

Things took a strange turn once again in February of 1882, when a man from Liverpool by the name of Derr, whose son died of lockjaw in Havre de Grace around the time of the Miller murder, said that he went to the Lutheran cemetery in Liverpool to visit his son's grave after the body had been shipped back home from Maryland and was surprised to discover that the grave was only half-filled with soil. It was a day or two later when the corpse was discovered at Girty's Notch. For years he had always suspected that his son's body may have been stolen and used as the infamous "substitute corpse". To satisfy his curiosity, he had the grave of his son re-opened, but the corpse was still inside the coffin.

The Legacy of Girty's Notch

While Samuel Albright never returned to Perry County-- assuming he'd ever left in the first place-- the infamous spot where the corpse was found continued to draw scores of visitors for decades. By the 1920s, the ancient Susquehanna Trail had become a well-traveled highway, dotted with motels and taverns and tourist attractions. Girty's Notch became one such attraction in 1928, after the State Highway Department placed a marker near an outcropping of rock that projected a face-like profile which, over the years, was said to be the profile of Simon Girty himself. Agnes Selin Schoch, who penned many interesting articles on local history for the Selinsgrove Times during this time period, wrote: The profile on this lower promontory is the face of a man with a mustache and cruel expression, which is much like that of Simon Girty.

Of course, since Girty died in 1819, long before the advent of photography, it's impossible to say with any degree of accuracy what the famed outlaw looked like in real life.

The legend of Girty's Cave flourished in the following years, even as the story of Sam Albright faded from memory. In 1929 the mountain hideout of Simon Girty was visited by the Pennsylvania Alpine Club, whose leadership included the illustrious Pennsylvania folklorist Henry W. Shoemaker. At the time of Shoemaker's 1929 visit to the cave, the property was under the ownership of the Hidden Inn, which was located south of Liverpool. Unfortunately, the increased volume of traffic and the precarious curve in the highway in the vicinity of Girty's Notch presented a danger that could not be ignored; traffic accidents, many of which were fatal, were a regular occurrence.

"When so many accidents occur at one curve on an important Pennsylvania highway as to make it impossible for maintenance forces to reset or renew guard posts and cable after one accident and before another occurs, it is really time to apply preventative measures," wrote Ammon Monroe Aurand, Jr., in 1931. "The unfortunate series of accidents occurring almost daily at Girty's Notch ought to be eliminated and can be, at little relative expense."

Aurand was widely-known throughout the state as an author of Pennsylvania history, and an influential one at that, and was working on a book about Simon Girty at the time. Aurand claimed that the cave was not worth saving because he could find no proof that Girty had ever used it as a hiding place. In a series of articles, Aurand called upon the Highway Department to eliminate the danger by straightening the deadly curve-- even if it meant the permanent destruction of Girty's Cave. Aurand proposed straightening the highway by filling in a stretch of the Pennsylvania Canal's Susquehanna Division, which had run parallel to the Susquehanna Trail since 1831. Sadly, the Highway Department took his advice, thereby destroying two historic landmarks in one fell swoop.

Just a few weeks after Aurand published his proposal, the State Highway Department awarded a contract to John H. Swanger of Lancaster to fill in the canal and widen the highway, and work was begun immediately. Ironically, this straightening of the curve has turned that particular stretch of Route 11/15 into a paradise for lead-footed drivers, and has done little, if anything, to reduce the number of fatal accidents. In fact, this author (who commutes along this stretch on a daily basis and has witnessed too many accidents to count) is inclined to believe that leaving the curve-- and the cave-- intact would've probably induced drivers to slow down to a safe speed, and would've preserved for posterity one of the most unique natural and historic landmarks in Perry County.

Sources:

Newport News, Aug. 8, 1879.

Harrisburg Telegraph, Aug. 11, 1879.

New Bloomfield Times, Aug. 12, 1879.

Perry County Democrat, Aug. 13, 1879.

Harrisburg Daily Independent, Aug. 14, 1879.

Harrisburg Daily Independent, Aug. 15, 1879.

Harrisburg Telegraph, Aug. 16, 1879.

Harrisburg Telegraph, Aug. 18, 1879.

Harrisburg Daily Independent, Aug. 18, 1879.

New Bloomfield Times, Aug. 19, 1879.

Harrisburg Daily Independent, Aug. 21, 1879.

Newport News, Aug. 22, 1879.

New Bloomfield Times, Aug. 26, 1879.

New Bloomfield News, Sept. 2, 1879.

Perry County Democrat, Sept. 3, 1879.

Harrisburg Daily Independent, Sept. 5, 1879.

New Bloomfield Times, Sept. 9, 1879.

Harrisburg Daily Independent, Sept. 13, 1879.

Harrisburg Telegraph, Sept. 22, 1879.

Harrisburg Daily Independent, Sept. 22, 1879.

Harrisburg Daily Independent, Oct. 3, 1879.

Newport News, Oct. 10, 1879.

Harrisburg Telegraph, Oct. 23, 1879.

Perry County Democrat, Jan. 28, 1880.

Altoona Tribune, Dec. 6, 1880.

Harrisburg Telegraph, Jan. 16, 1882.

Harrisburg Telegraph, Feb. 11, 1882.

Harrisburg Telegraph, March 9, 1882.

Perry County Democrat, August 8, 1928.

Altoona Tribune, February 20, 1929.

Shamokin News-Dispatch, March 14, 1931.

Danville Morning News, June 3, 1931.

Comments

Post a Comment