The Despicable John Gampher

In the backwoods of Cumberland County live some of the kindest, gentlest souls you could imagine; decent, God-fearing folks who'd gladly give you the shirt off their own back or drive you into town if you should happen to run out of gas on a lonesome country road. But the backwoods of Cumberland County has also been the home to some of the most depraved and reprehensible folks who ever trod God's green earth. One example of such human vermin is John Gampher, who, in the late 19th century, pulled off one of the most diabolical stunts in the annals of Pennsylvania crime.

Situated between Carlisle and Shippensburg in the South Mountain region, the village of Huntsdale straddles the southern bank of Yellow Breeches Creek. Along this stream can be found railroad tracks which once belonged to the long-forgotten Harrisburg & Potomac Railroad. Employed by this railway as a sectionhand was 39-year-old John Gampher, who, in 1890, shared a home with his wife, Rebecca, along with their 10-year-old son Joseph and 15-year-old step-daughter, Bertie.

Rebecca McCoy Stringfellow had married John Gampher in May of 1875 after the death of her first husband, but the marriage had been unhappy from the very beginning. He kept his wife engaged in tiresome tasks and tedious chores without showing the least bit of affection, and, as a result, Rebecca grew melancholy and old before her time. Worse still, John often made Rebecca the victim of his violence, beating her severely for any reason he could find-- or for no reason at all. Friends often encouraged Rebecca to abandon her brutish husband, but she had always considered her marriage vows sacred, reminding them that she had promised to remain faithful and loyal "for better or for worse".

As terrible as her marriage might have been, things grew considerably worse over the fall and winter of 1889. The beatings took on a new level of brutality, and, perhaps most shocking of all, her husband and daughter appeared to be acting "inappropriately" toward each other. Making such a horrible accusation was simply not an option to the straight-laced 35-year-old woman. This secret affair she kept under wraps, though she confided to her brother, William McCoy, that she feared John Gampher would kill her some day.

Agonizing Screams and a Dark Family Secret

On Tuesday, June 26, Rebecca woke up in the morning feeling under the weather. The night before, she had taken a small dose of laudanum mixed with Leberknight's Liniment, a popular local drugstore medicine of the era. At around six o'clock on Tuesday morning, her husband offered her another dose of medicine, dropping eight drops of laudanum upon a sugarcube and ordering her to take it. She refused at first, but he insisted. She swallowed the medicine and John Gampher left the house.

A short time later the neighbors were attracted to the Gampher home by Rebecca's agonizing screams. When they arrived, the found Rebecca in convulsions on the floor, her muscles twitching violently. She complained of terrible pain in her spine and in the soles of her feet. She begged her neighbors to hold her down, out of fear that her back was breaking. "I believe I've been poisoned," she said to Mrs. John Young between spasms. She died two hours later before help could arrive, but held on to life until she revealed the darkest of the Gampher family's secrets.

Neighbors set out in search of John Gampher, but he was nowhere to be found. He finally returned home about an hour afrter her death, but expressed little emotion at the news of his wife's passing. Some of the neighbors took notice of this lack of emotion, and this would be recalled at Gampher's trial.

Rebecca Gampher was laid to rest on Saturday at the Huntsdale Church of the Brethren cemetery. At the funeral, Rebecca's brother was informed about the forbidden relationship between John and his step-daughter, Bertie Stringfellow. So revolting was this news that William McCoy at first refused to believe it, but the statements were corroborated by other neighbors who had been at Rebecca's side at the time of her death. Upon returning to Carlisle after the funeral, McCoy accused Gampher of murder before Magistrate Allen and a warrant for Gampher's arrest was placed in the hands of constables Thomas James and Willis Humer.

The Undertaker's Story

Later that evening, constables James and Humer found John Gampher at his home, seated in a room with Bertie and John's ten-year-old son. They came upon him unexpectedly and Gampher offered no resistance when he was placed under arrest and taken to jail in Carlisle. The children, meanwhile, were taken to the home of a neighbor. On Sunday morning, District Attorney Maust and Coroner Davis traveled to Huntsdale to search for additional evidence. After interviewing several neighbors, the men arrived at the conclusion there was grounds for a post mortem examination, even though Rebecca's body had already been buried. This conclusion was reached largely on the account of the undertaker who prepared the corpse, Levi Kissinger.

According to Undertaker Kissinger, he found that Rebecca's corpse was decomposing far faster than normal, and that it did not have the appearance of a person who had died from natural causes. The woman's ears, neck, shoulder and back were discolored, almost black in color. The limbs were rigid, the jaws locked. Suspecting that her death might not have been natural and that exhumation might be necessary, Kissinger did not use embalming fluid on the body. When Kissinger asked Gampher how his wife had died, the man just shrugged. "Heart disease, I suppose," was his unemotional reply.

The Case Against Gampher

Mrs. Philip Foust had been one of the neighbors summoned to the Gampher house on Thursday morning. Bertie Stringfellow had knocked on her door, crying and claiming that her mother was "strangely sick". Mrs. Foust entered the home and observed the dying woman's painful convulsions. Rebecca told her that her husband had forced her to take the medicine, and had left the house soon after the convulsions began. This story was also corroborated by Mrs. John Young, Mrs. Williamson, and Mrs. Himes. John Young told authorities that Gampher had said that he'd given Rebecca "eight drops of laudanum mixed with Leberknight's Liniment." Bertie claimed that she had seen her step-father give the medicine to her mother, but had tried to stop him.

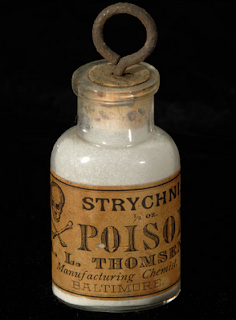

However, a druggist from Carlisle named Joseph Haverstick claimed that he had sold a customer four grains of strychnine on May 20, one month before the woman's death. Haverstick said that the customer wanted the poison in order to "kill mice". Police brought the druggist to the Cumberland County jail and Haverstick positively identified John Gampher as the customer.

On Monday, the body of Rebecca Gampher was exhumed and a post mortem examination conducted by Dr. A.R. Allen of Carlisle and Dr. J.H. Longsdorf of Centerville. The stomach was removed and turned over to Dr. Horn, a Carlisle chemist, for analysis. An inquest was held and a verdict was reached. Rebecca Gampher, they believed, had been poisoned by her husband.

|

| Huntsdale Church of the Brethren Cemetery, where Rebecca Gampher is buried. |

The Murder Trial

On July 17, Judge W.F. Sadler appointed J.E. Barnitz and S.M. Leidich as attorneys for John Gampher, as he could not afford legal representation. Attorney Francis J. Weakley was also part of the defense team. Meanwhile, Dr. Horn, the chemist, had completed his analysis but refused to make his findings public. He sent a sealed report to the county commissioners on August 13. These finding would not be divulged until the trial, which had been scheduled for November.

On Wednesday, November 12, 1890, the trial began with District Attorney Maust declaring in his opening statement that the immoral relationship between Gampher and Bertie Stringfellow was the motive for murder. The sensational nature of the case caused the courtroom to be packed the following morning when testimony resumed. Bertie Stringfellow was the first witness called that day, though she was not questioned about her sexual relationship with her step-father. Undertaker Kissinger also took the stand on Thursday, as did Dr. Longsdorf, Dr. Allen and Coroner Davis, all of whom provided damaging testimony against Gampher.

However, it was the testimony of the chemist, Dr. Horn, which everyone was desperate to hear. Horn was called to testify later that afternoon, but the defense team did its best to call his credentials into question before objecting to him as an expert witness. Judge Sadler overruled this objection and Horn described, in great detail, his complicated method of analysis. He stated that strychnine had been detected in all three of the tissue samples he tested; one from the liver, one from the small intestines, and one from the stomach. According to Horn, a lethal dose was between one half to two grains. Later that evening Joseph Haverstick was called as a witness and stated that he had sold Gampher four grains of strychnine at his Carlisle drugstore.

On Friday morning, the question of motive was finally brought up. Scott Magaw, a hotelkeeper from Newburg, testified that on December 26, 1889, a man giving his name as John A. Gampher checked into his hotel accompanied by a young girl whom he claimed was his daughter. He asked for a room with only one bed, and, according to Magaw, the guests went to their room early in the evening and remained there until morning, when they left for Roxbury to visit a friend named Peisel (the husband of Rebecca Gampher's sister, Margaret). The next witness, Mrs. James Dixon, stated that for one year the Gampher family lived in a house that she owned, and during that time had caught Gampher and Bertie in bed together while Mrs. Gampher was away. Margaret Peisel was called to the stand and testified that neither John Gampher nor Bertie Stringfellow had visited her home in December of 1889. Bertie Stringfellow was then recalled to the witness stand and testified that she was 16 years of age and was presently pregnant with her step-father's child.

On Saturday afternoon, John Gampher took the stand. He claimed that his wife had been in poor health ever since they were married fifteen years earlier. As for the strychnine, he said that he and his wife had used it the same day that it had been purchased, by placing it on bread and setting the bread in the cellar. As for the visit to Margaret Peisel, Gampher said that he had changed his mind after checking into the hotel with Bertie. He claimed that, because of bad weather, they had not made the trip.

After the closing arguments had been delivered on November 17, Judge Sadler dismissed the jury and at 4 o'clock they retired. They remained in deliberation until 9 o'clock, when they returned with a shocking verdict: Not guilty.

The Ballad of Bertie Stringfellow

Although John Gampher was acquitted of murder, the testimony given during his trial provided the commonwealth with enough evidence to charge him with statutory rape and adultery. By the time the case went to trial in May of the following year, Bertie had given birth to John's child and had become a resident of the county almshouse, where she worked as a cook for a salary of one dollar per week. Once again, Gampher would be represented in court by attorneys Leidich, Barnitz and Weakley. This time, however, the jury would not rule in their client's favor. On May 23, 1891, Gampher was convicted of "adultery, bastardy and abuse of a woman child" and sentenced to seven years and four months of solitary confinement and hard labor at Eastern Penitentiary.

As for Bertie Stringfellow, it would appear that, upon leaving the county almshouse, she would become a denizen of the various "bawdy houses" of Carlisle's disreputable Foundry Alley. In September of 1894, Robert McCleaf was arrested for assault and battery against Bertie, who, apparently, was one of the prostitutes employed by McCleaf's aunt, Clara Kircher. The following year, she married Jesse Smith and lived a respectable, happy life in Steelton, Dauphin County, until her death in 1946 at the age of 72.

Gampher's Final Years

While Bertie Stringfellow's life may have had a happy ending, the same could not be said for her stepfather. In 1895, the Board of Pardons rejected John Gampher's plea for clemency. Upon his return to Cumberland County in 1897, he was arrested on five charges of larceny, but later acquitted. He relocated to York County, where he married a young woman eighteen years his junior by the name of Lizzie Lowe, but she succumbed to pneumonia in 1908. By all accounts, his marriage to Lizzie had been just as tumultuous as his marriage to Rebecca. His new wife had a reputation for being less than faithful, and this inspired Gampher to assault one of her suitors on Valentine's Day of 1905. "If you ever come into my house again or talk to my wife, you are a dead man, Bill Hubley!" he shouted, before striking him over the head with a chair.

Impoverished, friendless and unable to support himself, Gampher's final years were marked by a series of arrests for minor offenses, which usually consisted of stealing food and other basic necessities. After being caught stealing oranges, meat scraps and candy from the Central Market in 1909-- the second such arrest in two weeks-- York authorities deemed him "feeble-minded" and committed him to the county almshouse, where he eventually died in obscurity and buried in a pauper's grave.

Sources:

Carlisle Sentinel, July 2, 1890.

Carlisle Weekly Herald, July 3, 1890.

Carlisle Weekly Herald, July 24, 1890.

Carlisle Weekly Herald, Nov. 20, 1890.

Carlisle Evening Herald, May 18, 1891.

Carlisle Weekly Herald, Oct. 13, 1892.

Carlisle Sentinel, Sept. 13, 1894.

Carlisle Evening Herald, Sept. 17, 1895.

York Gazette, Feb. 16, 1905.

York Gazette, April 10, 1909.

Comments

Post a Comment