Tower City Fugitive: The Hunt For George Wessner

In March of 1929, the Schuylkill County borough of Tower City became the scene of an intensive manhunt. On the loose was 22-year-old George Wessner, a young out-of-work miner who fled into the wilderness after murdering his older brother, never to be seen again.

On the evening of Monday, March 18, an argument took place between George and his 32-year-old brother, William, inside the living room of their home on the corner of Sixth and Wiconisco streets. George and William had been at odds for several months, and that the brothers often went weeks without speaking to each other. Shortly after 8:00 that evening, William was reading in the living room when George came downstairs and said, calmly, "Bill, I'm going to shoot you."

"Quit your kidding," replied William, without looking up from his book. George made hos way to a cupboard and seized a .38 caliber revolver. William threw down his book and raced for the door. He had only made it about fifty feet when five shots rang out. The last bullet struck William under the right arm, penetrating the lung. George fled the scene, while his dying brother staggered to the home of a neighbor, Jacob Houtz. "George did it," gasped William, clutching his chest and falling onto a couch in Houtz's kitchen.

Houtz immediately summoned help and Dr. Stutzman, a local physician, raced to the Houtz home at 507 Wiconisco Avenue, where he found William Wessner conscious, but his efforts to stop the bleeding were futile. William died at 8:38, but gave no indication as to the reason for the shooting. Their widowed mother, Mrs. Agnes Wessner, was at church at the time of the shooting, and arrived at the Hautz home at the same time as the doctor. She broke down in tears at the sight of her dying son, cradling his head in her arms and asking him to tell her what had happened. "George shot me, mother," he said softly. Police officers and concerned neighbors soon filled the tiny room. The look on the doctor's face told the grieving mother that her oldest child was beyond help. Suddenly, William became alert and he stared at the roomful of faces. "I'm going over," he declared before drawing his final breath.

After Dr. Stutzman pronounced William dead, his body was released to Undertaker Dreisegacher by Deputy Coroner David Hawk, who concluded that William had died from an internal hemorrhage caused by a punctured lung. We would be laid to rest at the family plot at Sacramento Cemetery.

According to relatives, George had been out of work for three years. He was the youngest of five brothers and two sisters born to William and Agnes Wessner, and was regarded as the black sheep of the family, preferring to spend his free time roaming the hills and forests. George was not a physically imposing presence by any means; standing just five feet and four inches, he was described as being on the "wimpy" side, having wild, bushy brown hair and a nervous condition which made him blink uncontrollably whenever he spoke. He walked with a limp on account of a mining injury he suffered as a teenager.

Earlier that fateful evening, William had gone next door to visit his brother Harry, where the two men had discussed their younger sibling's inability to find a job. According to Harry Wessner, George had always been touchy on the subject of being unemployed.

A Posse is Formed

By nightfall, a posse of twenty residents were searching the woods around Tower City looking for the killer. The prevailing opinion was that George Wessner had fled in a westward direction. Meanwhile, police investigated a report from across town that a gunshot had been heard near the swimming dam. Thinking that George might have taken his own life, authorities searched the area along Wiconisco Creek, but but found no trace of the fugitive.

In the morning, the search was aided by ten State Police troopers, who focused their search on Peters Mountain and Clark's Valley, where they believed the killer was hiding, possibly near the home of his sister. A search party also went to Goldmine Gap to check on a hunting shack owned by the Wessner brothers, but no clues of recent habitation were found. Police widened their search to include the Pottsville and Pine Grove areas. Police as far away as Frackville were placed on alert after an overnight theft of two blankets from an automobile occurred there, leading police to wonder if the fugitive's plan was to stockpile supplies and provisions. Later that afternoon, the swimming dam was drained in connection to the suicide theory, but the body was not found.

The search dragged on for weeks, and the weeks turned to months. By summer, State Police had investigated dozens of George Wessner "sightings" throughout Schuylkill and Dauphin counties, but could not prove that the man seen by witnesses was the same man who had shot and killed William Wessner. Another large posse was formed in July after William Wert, a farmer from Millersburg, reported a suspicious young man in ripped and tattered clothing crossing his field. The same man was also seen by fishermen along Little Wiconisco Creek, and a man fitting the same description had also knocked on the door of and elderly woman, Mrs. Mary Dressler, seeking shelter for the night. This ragged wanderer was also seen a week earlier prowling around the woods of Armstrong Valley. The following month, a group of men hunting for groundhogs near Rife came across a vagabond sleeping atop a pile of hay inside an abandoned barn owned by Hiram Landis. Believing the man to be Wessner, they notified Officer Albert Hartman of Millersburg, but the vagrant was gone by the time he arrived.

|

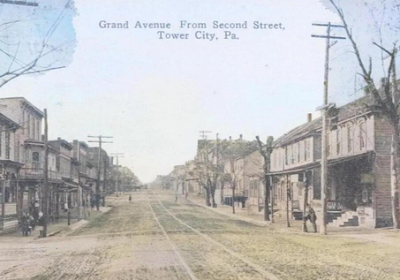

| Undated street scene, Tower City |

The Hunted Becomes the Hunter

In November, the best chance of apprehending Wessner came when the killer's sister, Lucy Shaffer, informed authorities that she had shot at a man who resembled him. The man had been attempting to enter the home in Upper Clark's Valley through a window when he was discovered by Mrs. Shaffer, who took aim with her rifle. She told police that she found blood outside the house, leading her to believe that she had wounded the intruder. When they arrived on the scene, they followed the trail of blood to a swamp, but the direction of the trail suggested that Wessner had headed toward the mountains. For the first time in ten months, it appeared that William Wessner's slayer would soon be captured. With the weather turning cold and the fugitive presumably injured and in need of medical attention, Tower City was buzzing with gossip about Wessner's imminent arrest.

Less than one month later, on December 18, the Shaffer home burned down under mysterious circumstances. Police ruled it a case of arson and the light of suspicion immediately fell upon George Wessner. Had the fire been set as an act of revenge against his sister for shooting him? Detectives believed this was the case. However, once again, the out-of-work miner managed to elude his pursuers.

After the fire, Lucy and her husband, John Shaffer, sought shelter in a Tower City apartment owned by John Peiffer. But things took a shocking turn the following morning, when the apartment mysteriously erupted in flames around six o'clock in the morning. Only the quick response from the Tower City and Williamstown fire departments prevented the home's total destruction. It now seemed clear that George Wessner would stop at nothing to get revenge against his sister. But while this made him a dangerous criminal, it also confirmed the assumption that Wessner was nearby, lurking in the shadows.

A Small Man At Large

Despite his habit of hiding in the vicinity, Wessner continued to baffle both local and state authorities. The search for the Tower City fugitive dragged on, much to everyone's amazement. Hundreds of strong, brutish mountain men had attempted to flee from justice in the wilds of Pennsylvania, only to be captured at the hands of lawmen. How, then, could a wispy limping wimp like George Wessner survive for so long in the rugged mountains of Schuylkill and Dauphin counties?

In September of 1930, more than a year after the murder of William Wessner, the Homicide Division of the State Police asked the co-operation of the Pottsville Police Department, who now believed that Wessner was being shielded by friends who lived there. Wanted posters were displayed throughout the city, but, once again, the trail led to a dead end.

By the following February, not long before the second anniversary of William's death, the hopes for a capture-- which had once seemed all but guaranteed-- appeared to crumble. Was George Wessner alive or dead? Had his friends been able to transport him to a different state, where he found a new life with a new name? Or had he frozen to death on a cold winter night in a lonesome mountain cave? Were his bones rotting away at the bottom of some abandoned mineshaft? Or was it possible that he was still in the vicinity, somehow able to go about his daily life without arousing suspicion? Perhaps he had changed his identity, or perhaps he had a sibling or two who sympathized with his plight, a relative who took it upon himself to hide the fugitive until the heat died down.

A warrant charging George Wessner with murder was still in the hands of Leroy Kopp, the chief of police of Tower City. Would it ever be served?

The End of the Search

The answer to this question is a resounding "no". Despite the best efforts of the State Police Homicide Division's best detectives and dozens of police departments, George Wessner was never found. It was as if the earth had swallowed him up completely-- and, considering the number of coal mines in Schuylkill County-- this might not be an exaggeration. This was the conclusion of many folks who lived in the area, though no evidence has ever been found to support this theory.

In May of 1937, Judge G.E. Gangloff of the Schuylkill County Orphan's Court declared George Wessner legally deceased, for the purpose of settling the family's estate. While this ruling brought some closure to the Wessner family, it did not let the killer off the hook entirely; Gangloff explained in his ruling that Wessner could be tried on the murder charge in the event of his subsequent return to society.

While this never happened, it might have played out as one of the strangest events in the history of Pennsylvania crime; since the death penalty was in effect, George Wessner could have potentially been the first person to be executed after being declared legally dead.

Sources:

Pottsville Republican, March 19, 1929.

Harrisburg Telegraph, March 19, 1929.

Harrisburg Telegraph, March 21, 1929.

Elizabethville Echo, July 18, 1929.

Elizabethville Echo, Aug. 8, 1929.

Harrisburg Telegraph, Nov. 9, 1929.

Elizabethville Echo, Nov. 14, 1929.

Mount Carmel Item, Dec. 18, 1929.

Elizabethville Echo, Dec. 26, 1929.

Shamokin News-Dispatch, Sept. 22, 1930.

Mount Carmel Item, February 19, 1931.

Pottsville Republican, May 4, 1937.

Comments

Post a Comment