Execution of a Voodoo Doctor

From the Colonial Era to the modern era, over one thousand criminals have paid for their crimes in Pennsylvania with their lives (and if you want to know all their names, check out this amazing list by Juan Ignacio Blanco). But one man, Lorenzo Savage, holds the distinction of being the only voodoo doctor executed by the Commonwealth.

The story seems like a tale ripped from the pages of a dime-store novel: A lovelorn nurse is brutally slain, her body found outside an abandoned mansion. In her hand detectives find an arrangement of playing cards, which they soon learn is the black magic "hand of death". Some seriously spooky stuff, indeed, but the tragic tale of Elsie Barthel is not a work of fiction. It really happened in Pittsburgh in the fall of 1923.

Murder at the Hussey Mansion

On an autumn night in 1923, a young woman and a man sat inside an old automobile rusting away under the tree-shrouded portico of the abandoned Hussey Mansion on Center Avenue. They were engaged in a serious conversation. A moment later, the woman reached into her coat and withdrew an envelope, which she handed to the man. Angry words were spoken; the young lady snatched at the envelope, trying to take it back. Angry words gave way to pushes and shoves, and the woman fled from the vehicle. The man got out and struck the young lady a vicious blow to the face with a clenched fist. She fell to the ground, then looked up to see the menacing figure hovering over her with a brick in his hand. Though it was dark, she could detect the maniacal gleam in the man's eyes. This was probably the last thing she ever saw-- other than the brick, which, in a terrible instant, came crashing down on her head.

It's impossible to say how many blows it took to extinguish the life of Elsie Barthel, a 27-year-old nurse employed by Dr. R.S. Marshall as a private secretary, but the crazed killer didn't stop bludgeoning her until his brick either broke or became too slippery with warm blood and gore. For whatever reason, the deranged assailant decided to reach over to the foundation of the building and yank loose a seventy-pound block of granite, which he raised overhead with both hands and dropped. A thud, a sickening crunch, then the sounds of hysterical laughter fading away as the killer retreated into the night, and all was once again silent and still on the grounds of the deserted mansion.

On the morning of Sunday, October 7, 1923, Patrolman Alexander McGonigle made a horrible discovery under the portico of the mansion, where the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center now stands. McGonigle found Miss Barthel lying face down, her life quite extinct. In a torn envelope beside the body were four playing cars-- the ace, deuce, and trey of diamonds and the five of spades. It made little sense to McGonigle, who had answered the call put out by Police Operator William Sloan, who had received reports of a missing woman.

Elsie's mother had returned to their home at 4620 Carroll Street around four o'clock on Saturday afternoon, just in time to hear the end of a telephone conversation between Elsie and a "Negro voodoo doctor" named Lorenzo Savage. The Barthels were familiar with Savage, who had once worked for Dr. Marshall as a butler. Elsie told her mother that she was going to meet Savage on Saturday night, though she did not provide a location, and that Savage had instructed her to place $300 in one envelope and the "charmed" cards in another. When she failed to return home the following morning, Mrs. Barthel contacted the police.

|

| Elsie Barthel |

The Hand of Death

Detectives frank Morgan and William Sullivan were the first to arrive on the scene after the ghastly discovery. They, too, were perplexed by the envelope and its contents, and by the empty blood-splattered envelope they found under Elsie's body. A few feet away they located Elsie's empty pocketbook. The body was taken to the morgue, where Dr. Wayne Ritchey performed a post mortem examination. Death was due to a fractured skull, though the rest of the body was uninjured.

Detectives questioned Elsie's younger sister, Laura, and John Knight, a brother-in-law, who told them about Elsie's conversation with Lorenzo Savage. Acting Superintendent of Police Robert McIntosh ordered Savage's capture, and he, along with his wife, were arrested at the home of C.S. Mitchell, where the couple had been employed since leaving the employ of Dr. Marshall several months earlier. A search of their room turned up a pack of similar cards, in which the ace, deuce and trey of diamonds and the five of spades were missing. At the police station, Savage denied any involvement, and subsequent interviews with local fortune-tellers revealed the dire meaning of the hand which Miss Barthel had been dealt.

Despite Savage's silence, Superintendent McIntosh and Captain Leff had all the evidence they needed. Nevertheless, they interviewed scores of witnesses to bolster their case. There was Minerva Rosaur and William Mickler, who had both seen a car parking under the mansion's portico, and had both heard a woman's chilling scream. "Don't do that!" the woman had cried.

News of the murder spread quickly. Relatives of Elsie Barthel were in a state of shock. Her employer, Dr. Marshall, was devastated. "Miss Barthel was my assistant and secretary for three years and my wife and myself found her indispensable," stated the distraught physician. "We cannot speak too highly of her ability and character, and we are sorely grieved to hear of her death."

A Motive

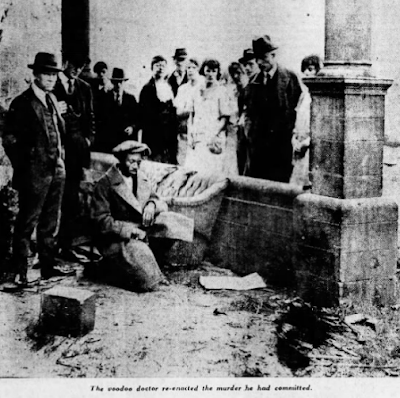

Though Lorenzo Savage was short in physical stature, the black residents of Pittsburgh's East End stood in awe of him, believing that he had the power to communicate with the dead, dispense charms and love potions and cast spells. As one Pittsburgh newspaper put it, "he was an inheritor of the weird rites of the African jungle." The night after his arrest, Savage confessed and was taken to the mansion to re-enact the crime in front of detectives, lifting the granite block and demonstrating how he had murdered the young nurse.

According to Savage, Elsie had asked him for a "charm" to extricate herself from a troubled love affair with a taxi driver named Walter Holly. The argument arose when, according to Savage, he opened the envelope to find only $32 instead of the agreed-upon fee of $300. This is what had driven him into a murderous rage.

In a bizarre twist of fate, after Savage fled from the scene on foot, he hailed a cab at East Liberty. He was picked up by Walter Holly. This led to Holly's questioning at the hands of the police, but when they discovered two of the dead woman's handkerchiefs in Holly's pocket, he was arrested on suspicion of being an accomplice to murder. As it turned out, however, the obsessed cab driver had simply kept Elsie's handkerchiefs as a souvenir. Although he would later be released from police custody, detectives took Holly to the morgue to view Elsie's body at his request. Upon viewing the corpse, he fainted.

"It was one of the strangest coincidences I ever heard of," recalled James Hoey, one the detectives who worked on the case, in 1936. "Here was this young man, a cabbie who, without knowing it, had driven the slayer of his sweetheart away from the district in which the crime was committed. It was hard to believe this hookup of the cab driver and Savage was only accidental... Things looked bad for this boy for a while. We could almost see him in the electric chair."

Trial and Execution

Lorenzo Savage went of trial for the murder of Elsie Barthel in February of 1924. Assistant District Attorney Harry A. Estep conducted the prosecution for the Commonwealth. To be fair, Savage's court-appointed defense team did him no favors; they could not provide a logical explanation for the missing cards in Savage's room, and Savage claimed that he had given his confession under duress and that someone else had committed the foul deed. The jury did not take long to find Savage guilty of first-degree murder and before Judge A.B. Reid passed sentence he asked the voodoo doctor of he had anything to say. "There are four persons that know I'm innocent," said Savage. "One is Almighty God, one is Elsie Barthel, one of them is the man or person who really killed her, and other is myself." Savage would pay for his crime in the electric chair at Rockview Penitentiary.

On Friday, March 28, after saying goodbye to his wife, Savage left county jail for the death house at Rockview in the custody of two deputies. With his execution slated for sunrise on Monday morning, Savage didn't have much time to acquaint himself with his new surroundings. His execution had originally been set for March 24, but had been postponed by Gov. Gifford Pinchot to allow Savage's friends time to raise money in order to bring his case to the Board of Pardons. Sadly, the friends who had regarded Lorenzo as a powerful magician endowed with God-like powers let him down when he needed them the most.

Nevertheless, Savage remained stoic until the bitter end and he sat unflinchingly in the chair as the first shock was administered at 7:10 on the morning of March 31. After a second shock, he was pronounced dead by prison physician Dr. C.J. Newcomb. It was reported in the Pittsburgh Courier that the executioner had applied 2,000 volts of electricity-- the lowest ever used in inflicting the death penalty-- instead of the customary 2,300. While some activists have argued this point as proof of racism on the part of the penal system (the executioner ostensibly wanted Savage to suffer an agonizing death), the fact of the matter is that, in terms of size, Savage was a thin wisp of a man barely taller than a child and 2,000 volts was more than enough to do the job. The killer gave no statement before his execution, and body was buried in the penitentiary cemetery.

Sources:

Pittsburgh Post, Oct. 8, 1923.

Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Oct. 9, 1923.

Chambersburg People's Register, Feb. 7, 1924.

Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, March 28, 1924.

Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, March 30, 1924.

Pittsburgh Press, March 31, 1924.

Pittsburgh Courier, April 5, 1924.

Pittsburgh Press, Aug. 9, 1930.

Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph, Feb. 17, 1936.

Comments

Post a Comment