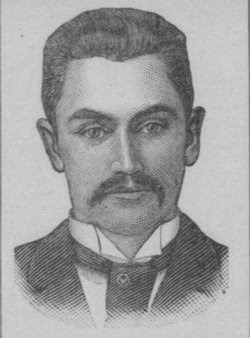

Matricide in McKean County: The Hanging of Ralph Crossmire

|

| Ralph Crossmire |

The rural village of Farmer's Valley in McKean County was thrown into a frenzy of excitement in the fall of 1892 when the body of Lucetta Crossmire, a middle-aged widow, was found hanging in her barn, about five miles north of Smethport on the banks of Potato Creek. Although the woman's death was the result of cold-blooded murder, it had been disguised to look like a suicide, and the person who was eventually executed for the crime was her own son.

It was a quiet Saturday afternoon in late November when Lucetta Crossmire headed to the barn to milk her cows, just as she had done countless times over the years. But as the afternoon gave way to evening and Mrs. Crossmire still hadn't returned, her elderly father-in-law, Daniel, grew worried. He sent for George Herzog, a seven-year-old who lived next door, and asked him to go out to the barn to see what the trouble was. After lighting a lantern the boy walked across the snowy fields to the barn and pushed open the door, and the warm yellow light illuminated a ghastly scene; hanging from the wooden beam of the barn was the lifeless body of the gray-haired widow.

George ran back to the house screaming in terror and told old Mr. Crossmire what he had seen, but the 82-year-old man was too weak and feeble to leave the house. "Run and tell the neighbors!" implored Mr. Crossmire. The boy complied and, before long, locals from the tiny village began to arrive. Inside the barn they found Mrs. Crossmire, her face smeared with blood and her tongue grotesquely protruding from her twisted mouth. A pool of blood was found four feet away from the body. Although the locals were simple folks, it was abundantly obvious that the widow had been murdered before she was hanged from the rafters. But who would so such a thing to a harmless old woman, and why?

Sheriff Grubb Deputy Sheriff Clark soon arrived on the scene, and agreed with the neighbors that Lucetta had been murdered, plain and simple. The back of the dead woman's head revealed bits of straw and other debris which indicted that her skull had struck the floor, while outside in the snow they found footprints leading away from the barn. A button from a man's coat, torn loose during the struggle, was found inside the barn.

The coroner arrived at Farmer's Valley the following morning. By the light of day the body, laid out on a stretcher in the living room of the Crossmire farmhouse, revealed the shocking brutality of the widow's last moments. The face of the dead woman was badly bruised, the nose crushed flat. Finger marks around the throat were quite evident, proving that Mrs. Crossmire's demise had been cruel and deliberate. The district attorney concluded that, in all probability, the crime had been committed by Lucetta's son, Ralph Crossmire.

Ralph Crossmire was a young man, 24 years of age, who had been living in Mt. Jewett for several months prior to his mother's death. Police discovered that he was seen in Mt. Jewett on Thursday evening, two days before the murder, boarding a train for Smethport. He returned to Mt. Jewett on 5:30 on Sunday morning.

Upon investigation it was revealed that Ralph and his mother had not been on the best of terms since the death of Mr. Crossmire ten months earlier. While the father was lying dead in the house the mother and son got into a heated argument over the dispensation of the dead man's estate, with both parties arguing that the farmhouse now belonged to them. Apparently Mrs. Crossmire won the argument, and Ralph gathered up all of his possessions and moved into a boarding house in Mt. Jewett.

Ralph was arrested by Sheriff Grubb on Monday morning. He didn't say a word. He merely got into the carriage and rode to Smethport without uttering a sentence to Sheriff Grubb or Deputy Sheriff Clark. He did not ask to speak to a lawyer after he was taken to jail, and he appeared unphased by his imprisonment and impending murder trial. Meanwhile a search was made of his rented room in Mt. Jewett, where authorities found a pair of overalls stained with blood.

On Saturday, December 4, Ralph Crossmire was arraigned before Justice of the Peace Ford in Smethport, with Eugene Mullin acting as counsel for the defendant. Crossmire was described as appearing "unconcerned" during the proceedings, with an immovable expression and an air of "supreme indifference". When it was his turn to speak he denied having anything to do with his mother's death, and claimed that it was a traveling salesman who had committed the foul deed. "I will not say who the peddler is, but I know," declared Crossmire. "It will all come out someday."

Ralph Blunders His Way To A Conviction

On March 5, 1893, Ralph Crossmire was found guilty of murder in the first degree. Even though the evidence against him was wholly circumstantial, the defendant's blunders on the witness stand proved to be his downfall.

It was the third day of the trial when Ralph took the stand on his own behalf-- a move that would be universally condemned by any smart defense attorney. Up until that point the prosecution had presented a strong, but by no means conclusive case, and the likelihood of an acquittal seemed very high. But Ralph thought that he could sway the jury by weaving a fantastic story explaining what he had been doing in Farmer's Valley on the day of the murder.

The problem, of course, was that no one had actually seen Ralph in the vicinity on the day of the murder. There had been no witnesses who could place him at the Crossmire farm, and he did not divulge his plans to anyone before leaving Mt. Jewett. Ralph didn't have an alibi, but he didn't need one in order to earn an acquittal-- it was the job of the prosecution to prove, beyond a shadow of a doubt, that he had been the killer of Lucetta Crossmire. And the prosecution may have been long on circumstantial evidence, but it was woefully short of direct evidence.

Yet, in spite of his lawyer's advice, Ralph took the stand and presented a confusing and convoluted story that the prosecution picked apart during cross-examination. This was what cinched the case for the commonwealth. If he had kept his mouth shut, he most likely would have walked out of the courthouse a free man. But instead, the jury found him guilty of murder in the first degree and the judge promptly sentenced him to death.

An Unusual Killing Machine

As so often happens to men condemned to death, Ralph's icy nerve and cold indifference began to melt as the day of his execution drew near. A reporter who visited him in jail a month before his hanging was surprised to find that the once vigorous and muscular young man had been transformed into a living skeleton with sunken, hopeless eyes. Out of pity, Sheriff Grubb had placed a rocking chair in the cell for Ralph to sit on.

"This jail life is pretty hard on a fellow," Ralph told the reporter. "But I suppose I've got to stand it." He then asked the reporter if he had heard any news of a pardon from Governor Pattison. When the reporter said he hadn't Ralph turned away dejected and discouraged. His petition for a pardon would be denied, and less than a month later Ralph Crossmire would be dead and buried in a pauper's grave at the McKean County Poor House farm.

|

| The barns of the county poor farm still stand today in Smethport |

At eight o'clock on the morning of December 14, 1893, Ralph ate his breakfast in silence and then spent an hour in spiritual consultation with a minister. At ten o'clock he was marched to the scaffold by Sheriff Grubb, perhaps surprised to see no great gathering of onlookers and curiosity seekers in the jailyard. Unlike the public spectacles in other counties, the hanging of Ralph Crossmire would be a small, quiet affair.

Upon arriving at the scaffold Sheriff Grubb gave Ralph permission to speak, but the killer's words were scarce. He told the small handful of witnesses that he had nothing to say but that he was innocent. The witnesses shivered and rolled their eyes; it was a bleak, cold winter morning and they all just wanted to go home. A black cap was pulled over Ralph's face and the noose adjusted around his neck. A moment later it was all over.

Perhaps the most interesting thing about the execution was that the gallows of McKean County were of a rather peculiar construction. The apparatus consisted of two solid hardwood posts positioned 11 feet apart, tilted to form a letter "A", with a heavy crossbeam connecting the two posts in the middle. Two pulleys were screwed into the crossbeam, carrying the half-inch rope that was used to launch Ralph Crossmire into eternity. And that is a fitting way to describe how the McKean County killing machine did its job. The condemned man is affixed to one end of the rope, and the other end of the rope is connected to a large box filled with hundreds of pounds of scrap iron. With the pull of a trigger the weighted box falls, and the condemned-- standing on the ground-- is yanked upwards by the neck. This method is extremely efficient, and in most cases death is instantaneous.

In May of 1894 the Crossmire farm was sold at public auction. The 113 acres in Farmer's Valley which had been squabbled over by Ralph and his mother were purchased, ironically, by Eugene Mullin-- the lawyer who had acted as Crossmire's defense attorney.

Comments

Post a Comment