Who stole the corpse of the councilman's son?

|

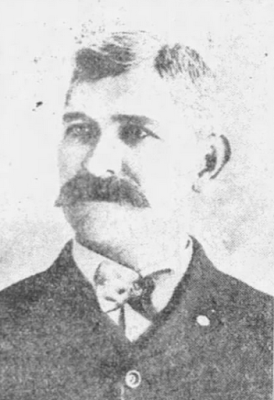

| James B. Spahr |

(Listen to the audio version of this story here)

During the early 20th century, James Black Spahr was a popular and well-liked member of the Chambersburg borough council. Unlike many local politicians, Spahr genuinely cared about his community and those who called it home. A devout Christian and family man, he earned the admiration of virtually everyone who knew him, and his many years of public service were unblemished by scandal.

Spahr was first elected to council in 1906 on the Fourth Ward's Democratic ticket and served three successive terms, from March of 1906 to January of 1913. During his tenure on the borough council, he served as chairman of the Street Committee, which was perhaps the most stressful position in local politics; the many complaints from townspeople about potholes, muddy alleys and public parking fell squarely on his shoulders. But James Spahr, who inherited his strong work ethic from his brickmaker father, was a tireless worker; rather than waiting for the slow wheels of city government to turn, he would often roll up his own sleeves and be the first one on the scene with a pick and a shovel. He was also a prominent member of the First Lutheran Church in Carlisle, a member of the Freemasons, and also belonged to the Franklin Fire Company.

Yet the life of James B. Spahr was not without tragedy.

1892 was a particularly cruel year to Spahr. In May of that year his young wife, Annie, passed away shortly after giving birth to twin sons. James and Annie had been trying for years to start a family; their first child, a daughter named Mary, died in infancy in 1881. Seven years had passed since before Annie became pregnant again, but this baby also died in infancy and was buried in 1888. When Annie became pregnant for the third time, at the age of thirty-two, it must have seemed like a blessing from heaven. But the blessing turned to tragedy and tragedy turned into a curse-- two weeks after Annie's death, one of the twins passed away suddenly. Seven months later the other twin, James F., would follow his brother to the grave. All three were laid to rest at Cedar Grove Cemetery, alongside the unnamed infant who died four years earlier.

This tragic twist of fate must have surely seemed like a curse to James, who also had a twin brother who passed away in infancy in 1858. Although his father, twin brother and first daughter were buried in the Spahr family plot in Carlisle's Old Graveyard, James had the body of the unnamed infant interred at Cedar Grove Cemetery in Chamberburg. Perhaps this was his effort to break the curse that had plagued his family, or perhaps it was simply a matter of convenience, now that he was a resident of Chambersburg.

At any rate, Annie and the twin sons were interred at Cedar Grove, and these burials caused James' lot to become congested. In 1909, he purchased two lots in a new portion of the cemetery that had been recently expanded. On Friday, December 3, he began the work of removing the remains of his wife and three children to the newly-purchased lot. Rather than hiring someone to do this ghastly chore, he decided to do the digging himself.

During the process of disinterring his wife and children, James made a horrible discovery: the remains of one of his sons was missing!

James was a practical man and rather than jumping to conclusions, he told himself that his memory must be at fault. He thought perhaps one of his sons had been buried in a different corner of the lot, and so he continued digging. When his search proved fruitless, he wondered if time had caused the bones of his son to turn to dust and disintegrate-- after all, it had been seventeen years since Annie and the twin boys had been buried, and there might be a chance, however slim, that the body could've returned to dust in that time. But this theory broke down when James realized that the other twin's coffin was still intact. Even the simple wooden box containing the remains of the baby who died in 1888 was in a state of fine preservation.

In order to prove to himself that he must have made some sort of mistake, James went to Carlisle the following day and consulted with his mother, who had attended all four of the funerals. Mrs. Spahr's recollection of the burial was exactly the same as her son's. By the time he returned home to Chambersburg, James had no other choice but to conclude that the body of his son had been stolen.

James reported the matter to the cemetery association, but nobody was able to clear up the mystery. The matter was then turned over to the police. In spite of an exhaustive investigation, the guilty party was never identified. As a matter of fact, there didn't even appear to be any suspects. James Spahr was liked by everyone and had no known enemies. Cemetery caretakers did not recall any cases of body-snatching having taken place between the time of the child's burial in 1892 and the discovery of the missing remains in 1909.

Who Did It... And Why?

While the mystery of who stole the corpse of the councilman's son remains to be solved, the motive for the crime remains a mystery as well.

As many people know, the stealing of freshly-buried corpses was popular during the late 18th and early to mid 19th centuries, as medical schools had a desperate need for human cadavers. This gave rise to Resurrectionists-- people who earned a living by selling bodies to medical schools.

Although the University of Pennsylvania was a notorious buyer of stolen bodies during the body-snatching era, changes in the law and stiffer penalties for the despoiling of graves had practically eliminated this practice by 1892. In Great Britain, passage of the Anatomy Act of 1832 virtually eliminated the practice of body-snatching altogether by giving medical schools legal access to unclaimed corpses from hospitals, prisons and poorhouses. Not long afterward, American cities such as Boston, Philadelphia, Washington and New York devised similar systems for providing cadavers to medical schools. In addition, Resurrectionists were often paid "by the pound", therefore making it highly unlikely that an infant's remains would be stolen for dissection purposes.

In all likelihood, the remains of James Black Spahr's son were probably stolen for an entirely different reason altogether. Surely the grave-robber was not after jewelry or valuables; if such was the case, the adjacent grave of Annie Spahr (who had died two weeks earlier and probably possessed a much larger fortune than her infant son) was still fresh. And neither robbery nor body-snatching would account for the missing coffin, which was rarely taken in the commission of these crimes.

Unfortunately, James B. Spahr went to his own grave without ever finding the final resting place of his dead son. In the summer of 1913, while serving as borough street commissioner, James traveled to Boiling Springs to inspect a paving project. As a former bricklayer he couldn't resist the urge to roll up his sleeves and join the workers in the laying of paving stones, and over-exertion caused him to collapse. The lingering effects of sunstroke took a toll on his health, and he passed away in January of 1915 at the age of 56.

Comments

Post a Comment