The Kidnapping of Warren McCarrick

Motorists crossing the Schuylkill River at Norristown will undoubtedly notice the large, 90-acre island in the middle of the river. Home to an old electric substation and criss-crossed by power lines, Barbadoes Island, at first glance, appears like an ordinary industrial site in the Philadelphia metropolitan area. However, with a history of European habitation that stretches back to the 17th century, this island has more than its share of secrets and mysteries.

Naturally, one of the more enduring mysteries is how the island got its name. In January of 2000, staff writer Joseph S. Kennedy of the Philadelphia Inquirer wrote about how "the origins of the island's name are a matter of conjecture", but stated that wealthy planters from the West Indies sent their children to be educated in Philadelphia during the colonial era. While it's true that both Philadelphia and the West Indies island of Barbados were both under British rule during this period, that doesn't explain how a non-tropical island in the middle of the Schuylkill River came to be known as Barbadoes Island.

To solve this mystery, we turn to Theodore Webster Bean's 1884 History of Montgomery County. Bean states that the island was first mentioned in an August 16, 1684 warrant from William Penn to Ralph Fretwell, a merchant from the West Indies. The reason why Fretwell never appeared as the legal owner of the island is because Penn, for whatever reason, withheld the warrant and ceded a different parcel of property to Fretwell. As a result, records show that Penn instead sold the island to Isaac Norris and William Trent. The island remained under Norris family ownership until 1771, when it was sold to Col. John Bull of Limerick Township.

It was Charles Norris who, sometime prior to 1770, erected a dam on the north shore of the island to provide water power to his grist mill. Col. Bull sold the island to Rev. William Smith who, in turn, sold the heavily forested island to John Markley of Norristown. It was Markley who, in the summer of 1804, erected the first permanent residence on Barbadoes Island. Markley promptly deforested the island to provide lumber for the growing community of Norristown. By the following year most of the trees were gone, and the island became a popular resort for affluent Philadelphians. Handbills from the era show that horse races were held on the island as early as 1805, and continued until construction of the Schuylkill Canal began in 1816. The Schuylkill Canal and Navigation Company owned the island for nearly a century. During this period several improvements were made, and Barbadoes Island became a popular fishing, swimming and boating destination.

Unfortunately, the dam also became a popular destination for distraught residents of the Norristown area intent on committing suicide. One such case occurred in January of 1874, when Mrs. Irwin Brendlinger, the wife of a local merchant, excused herself from a tea party at her home and disappeared. When her body was recovered the following day, it became evident that she had stripped off her clothing, stood on the dam abutment, and jumped into the water to her death. Another remarkable suicide took place in 1898. After Kate Sherman "murderously assaulted" her husband, she threw herself into the deep water behind the Barbadoes Island dam. It took over a month to find her body.

|

| The Barbadoes Island substation, as it appears today |

The McCarrick Case

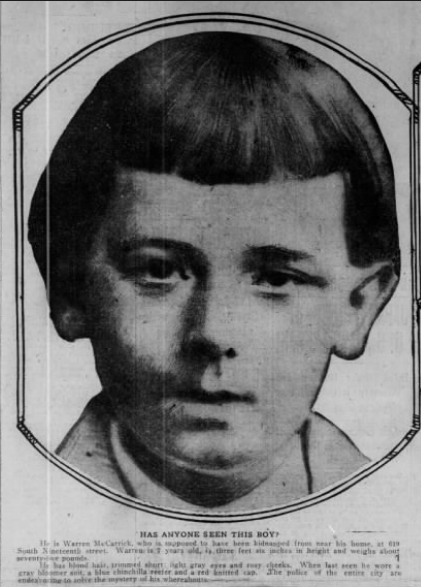

Of all the remarkable incidents to take place at Barbadoes Island, none garnered as much attention as the kidnapping of seven-year-old Warren McCarrick in 1914. What makes the McCarrick case so remarkable is that the child was abducted in broad daylight on a busy street, while Warren was playing in front of his home.

It was the afternoon of Wednesday, March 11, when Warren was last seen, playing in front of the family home at 619 South Nineteenth Street in Philadelphia. Normally, he would have been in school at this hour, but a bout of whooping cough had kept him home, and his mother felt that playing in the fresh air would help alleviate his discomfort. The boy's father was employed as a clerk in the Recorder of Deeds' office at City Hall, and, as a humble public servant with a modest income, it seemed strange to most people that James McCarrick would be the target of a kidnapper's ransom demand. Only a few people knew that Warren's mother was a wealthy woman; as a result, police were reluctant to believe that the child was taken by kidnappers. It wasn't until the night of Friday, March 13, that police got involved, when Captain of Detectives Robert D. Cameron assigned five officers to the case.

By Sunday, police had developed two theories regarding the boy's disappearance. The first was that Warren had been abducted by "degenerates" for immoral purposes before being murdered and his body hidden. The second theory was that Warren had been mistaken for the child of wealthy parents. As bizarre as it may seem, police actually considered the first possibility to be more plausible. The only lead they had to go on was a statement from Charles Daniels, who operated a feed store. Daniels claimed that he had been taken away in a covered wagon at the corner of Nineteenth and Bainbridge Streets by two men who were dressed like farmers.

When it came to running down leads, no one was more determined than James McCarrick. From sunrise to sunset, the boy's father questioned everyone he could-- his son's playmates, their parents, even total strangers. He implored authorities to search nearby abandoned buildings and vacant homes, out of the possibility that Warren might have gone exploring and had accidentally locked himself inside. The police explored this possibility, but they were unable to find any clue that could lead them to the missing seven-year-old.

What the Feed Store Proprietor Saw

Charles Daniels told detectives that he had seen Warren enter the covered wagon voluntarily, after the two men had stopped at the corner to chat with him. One of them men remained in the wagon while the other alighted, and was described as a tall, heavyset man with a gray overcoat and a soft hat of a variety favored by laborers and farm workers. The man who remained inside the wagon sat so far in the back that he could not be identified by Daniels.

A flood of reports reached the police from others who claimed to have seen the wagon in question. One witness, Walter Byler, said that he saw a boy riding in a wagon between Jeffersonville and Norristown. The wagon matched the feed store owner's description, and Byler claimed that the child was crying.

Working on this theory, police arrived at the conclusion that the two farm hands were degenerates, who probably drove the child to a desolate part of New Jersey. Philadelphia police notified the authorities in New Jersey and requested a search be made for a boy fitting Warren's description.

As is usually the case with all reports of missing children, the parents were not above suspicion. James McCarrick was grilled by detectives, who were soon convinced that domestic troubles played no part in the baffling disappearance. However, the fact that McCarrick refused to offer a reward for the return of his son left some people scratching their heads; in fact, he even refused to allow his friends to put up the money for such a reward. A few days later McCarrick begrudgingly changed his mind, allowing his friend, City Treasurer William McCoach, to put up $1,000 for the safe return of the missing boy. When a group of wealthy Philadephians offered an additional $2,000 in reward money, McCarrick protested vehemently, arguing that such a large reward might move Warren's abductors to murder.

By the following week, detectives had become thoroughly baffled by the lack of clues. If this had been a case of kidnapping, surely the boy's abductors would have made some demand by now. That the child was so well-known to his neighbors and the residents of Nineteenth Street led many to question the kidnapping theory, as it would have been nearly impossible for Warren to be spirited away without attracting anyone's attention. Although a handful of possible suspects had been hauled in for questioning, detectives were unable to make any headway in their investigation.

On March 17, the Philadelphia Inquirer reported that the lone lead in the investigation had gone up in smoke. The owners of the covered wagon which had stopped at the corner of Nineteenth and Bainbridge came forward to identify themselves, claiming they had not seen Warren McCarrick on the day of the disappearance, as the feed store proprietor had told authorities. The two farmers, who resided in Delaware County, were able to prove their case to Detective Cameron. The investigation was right back to where it was on the afternoon of the lad's disappearance; it seemed as if he had vanished into thin air.

At this point, nearly every clairvoyant and quack from Boston to Miami descended upon the McCarrick home, claiming that they could find Warren. The police department assigned a guard to keep these opportunists and fame-seekers at bay, but some were able to slip past the guard. One woman, a New York socialite named Beatrice Hampton, succeeded in speaking with the boy's father, assuring him that she had a foolproof system for finding missing persons. Hampton claimed that she merely had to lock herself inside a hotel room and focus on the missing person, and in two hours she would have a vision. According to Hampton, she had aided law enforcement agencies in New York, San Francisco, and all places in between with this "surefire" method. Though Detective Cameron was dubious of this claim, James McCarrick agreed to give her a shot. To nobody's surprise, after two hours had elapsed, Ms. Hampton failed to make an appearance. The McCarricks never heard from her again.

Warren's father also handed out articles of the boy's clothing to the mob of clairvoyants, all of whom promised to be able to find Warren if only they were armed with one of the child's personal belongings. When a newspaper reporter asked James why he complied with these requests from fortune-tellers and amateur sleuths, his explanation was perfectly rational; by giving them what they wanted, it would keep them out of the way of the professional crime solvers.

Meanwhile, nearly half of the city's police force was engaged in sweeping the greater Philadelphia area for clues. From the ritzy Fairmount Park boathouses along the Schuylkill River to the dilapidated fish shacks along the Delaware, no stone was left unturned. Even local Boy Scout troops got involved in the search. But after a week had passed without a scrap of evidence being uncovered, it seemed that all hope was lost. But things were about to change.

A Cryptic Letter and Doctor Goodbread

On Monday, March 23, James McCarrick received a typewritten letter claiming to have been penned by his son's abductors. The cryptic, rambling letter read: "Now that so much money has been placed on your son's return, I want to say that we will return him only on receipt of $7,500. He is safe, but unless we hear definitely through the papers within a day or two he will be safer where we expect to put him than if you had him with you. Further details will be sent if the newspaper items are satisfactory."

Not willing to place all their resources into this clue-- for the letter very well have could been written by a hoaxer-- detectives continued to run down leads as far away as Camden and Atlantic City. Armed with grappling hooks and searchlights, officers aboard the police tugboat John E. Reyburn dragged the Schuylkill River from the Chestnut Street Wharf to League Island, on a hunch that the young boy might have fallen into the river after straying away from home. They returned to shore empty-handed.

"We are as far away from a solution of the mystery surrounding Warren's whereabouts or the manner in which he was lost or stolen as were were on the day he disappeared," said the boy's father after the search of the river. "Under the present circumstances it would be a satisfaction to know that the little fellow is dead. Such a tragedy would greatly shock us, but it would be better than laboring under this awful suspense and the fear that he is meeting a terrible fate."

Convinced that the ransom letter was a hoax, authorities focused their efforts on two men upon whom they had kept under constant surveillance. On March 28, it was reported that arrests in the case were "imminent", and that it had been an informant who tipped off detectives. Police introduced the informant to the "Rogues' Gallery"-- a collection of photographs of known criminals and men and women of uncertain moral character-- and the informant picked out two colored men who had served time on multiple occasions. Armed with copies of the photographs, Detectives O'Connor, Sullivan and Gleason set out in pursuit of the suspects, who were identified as Walter "Chalky" Kane and Allan "Big Boy" Speller. Officers were stationed at all railroad depots, wharves and ferries to prevent their escape from the city.

The police department had to eat crow the following morning, however, when they issued a statement declaring that their "informant" had been a phony. Personal animosity, they claimed, had been behind the bogus information. The informant was revealed to be "Dr." Henry C. Goodbread, an herb dealer from Woodbury, New Jersey. Like the men he fingered, Goodbread was also a black man who had engaged in unsavory activities. Goodbread accused the two men because they had swindled him in a game of billiards the previous summer.

From Broad Street to Barbadoes

Just when it appeared that all new leads had been exhausted, a witness came forward and confided in City Treasurer William McCoach that he had proof that Warren McCarrick had been kidnapped and taken to Barbadoes Island in the Schuylkill River near Norristown, where he was kept prisoner until March 28, when his captors carried him off to another location. The witness claimed that he had seen a covered wagon while driving near Bridgeport, and his description tallied with the those given by other witnesses who had claimed to have seen the same wagon on the day of Warren's disappearance. Was it possible that the feed store operator who first reported the covered wagon had simply misidentified it? Police thought this might have been the case, and this new information revived their stagnant investigation.

When police made a thorough search of the large island, they were shocked to find a boy's footprints in the mud, just where the anonymous witness had said they would be. According to this witness, he was looking in the direction of Barbadoes Island when he spotted a young boy running along the shoreline near the railroad bridge calling out for help to a man in a rowboat. The boater did not hear or see the boy, and this compelled the witness to pay a visit to McCoach who, in turn, told the story to Detective Captain Cameron. Their search of the island also found evidence of recent occupation in two old, abandoned shacks. When it was learned that the covered wagon had been seen in nearby Bridgeport over the weekend, it appeared that the mystery of Warren McCarrick's disappearance would soon be solved.

But then came another mysterious letter.

It was a local attorney named Samuel Ephraim who had received the crudely-written letter on March 31, in which the author claimed that he was a German farmer who had been in the vicinity of the McCarrick home on March 12. According to the letter, the boy had accidentally been kicked by the farmer's horse and killed. Fearing arrest, the farmer put the body in his wagon and conveyed it to his farm for burial. So much confidence was placed in the note that Detective Captain Cameron agreed to offer the farmer immunity from prosecution if his claims turned out to be true.

After discussing the matter with Judge Patterson, the following advertisement was placed in Philadelphia papers by Cameron:

"There is nothing to fear. Have seen the parties necessary and immunity is guaranteed. Please call at once and I will take your part."

Of course, no one contacted Cameron, and since the letter had been written after it had been reported that a boy had been seen screaming for help on Barbadoes Island it seemed that the "German farmer" had been a red herring-- presumably written by one of the culprits-- to muddy the waters of the investigation. But if this was the case, the perpetrator had made a vital mistake; the envelope in which the letter had been sent featured a peculiar flap that was different than those found in common envelopes. In order to crack the case, authorities would have to track down where the peculiar envelope had been purchased.

Detective Frank O'Connor discovered that there were only three boxes of stationery that featured the odd flap in all of Philadelphia. It was a new envelope design, which the manufacturer had sent to local stores as samples. It was learned that one of the boxes had been purchased by a well-dressed couple in their 30s as a gift, along with birthday cards. The other purchasers had also been well-dressed and as this new type of envelope was rather expensive, it made little sense that an immigrant farmer could afford to buy it. This led authorities to believe that the writer of the letter had stolen the stationery. If this was the case, it would suggest that the kidnapper was either careless-- or brilliant in a diabolical sort of way; because of this detail, detectives were unable to make a link between the author of the letter and the customers who had purchased the stationery.

On April 12, one month from the day of Warren McCarrick's mysterious disappearance, Detective Frank O'Connor stated that the investigation would be shelved until new evidence surfaced. "There seems nothing left for us to do but wait until something definite turns up," he told reporters. "Since the day the boy disappeared we have considered the theory of kidnapping first, although no motive for such a crime has been found."

If Warren had indeed been abducted, money would have been the presumptive motive. But when the boy's grandmother broke her silence and told newspapers that she wasn't nearly as wealthy as some people had reported her to be, it was a decision that might have been fatal-- at least to one seven-year-old child. The realization that there would not be a big pot of gold at the end of the rainbow might be an impetus for murder; if the kidnappers saw no purpose for holding Warren as a prisoner, there were only two viable options. They could either release him, or they could kill him.

The Finding of the Body

On June 16, ninety-six days after Warren McCarrick vanished from his home at 619 South Nineteenth Street in Philadelphia, a badly decomposed body was fished out of the Delaware River off Vine Street by a barge crew. How the boy met his death, and how his body ended up in the river, baffled experts; but the one thing of which they were certain was that Warren McCarrick had been found at last. It was Mrs. McCarrick who made the identification at the morgue, based on scraps of underwear found on the remains of the tiny body.

Surprisingly, Detective Captain Cameron concluded that Warren had died of accidental drowning, even though evidence seemed to disprove this theory. For starters, Nineteenth Street is much closer to the Schuylkill River than to the Delaware. If Warren had wandered away from home only to drown in the Delaware, he would have had to travel five city blocks east to Broad Street, then proceed another twenty blocks or so to the Delaware River, at a point near Penn's Landing, crossing railyards, industrial sites, and several major thoroughfares along the way. This would be a difficult task for any able-bodied adult, much less a seven-year-old child with whooping cough. And if he had drowned in the Schuylkill River and his body swept downstream to its confluence with the Delaware, how did it manage to float upstream to the location where it was discovered?

In all probability, the boy seen calling for help along the shoreline of Barbadoes Island was indeed Warren McCarrick. Because the island had been abandoned by that time (the power station on the island would not be constructed for another eight years), it would've been an ideal location to hold Warren prisoner until his captors could decide what to do with him. The long-forgotten shacks on the island did show signs of recent habitation, and the footprints in the mud proved that the witness who went to McCoach had been telling the truth. Who else could it have been if not Warren McCarrick?

Did the kidnappers discover that Warren's grandmother was not as wealthy as they had hoped, killed the boy, then dumped his body in the Delaware? This seems to be the only likely scenario. And if this is the case, the perpetrators surely must have been locals.

Although the autopsy revealed no injuries or signs of foul play, the McCarricks insisted their child had been the victim of murder until the end of their days. On September 17, 1914, just three months after Warren's body was found, his grandmother, Annie McCarrick passed away at the family home on South Nineteenth Street. Her estate was valued at just $6,400.

Assuming that the kidnapping theory was correct, the perpetrator, or perpetrators, were never caught. However, in 1916, a mysterious letter was written to the father of Richard Meekins, a young Philadelphia boy whose disappearance bore an uncanny similarity to the disappearance of Warren McCarrick. In the highly-detailed and lengthy anonymous letter, the writer boasted that was the one who had kidnapped and murdered McCarrick, and claimed responsibility for the abduction and murders of several other local boys, providing details that authorities had never divulged to the public. The identity of the writer was never ascertained.

Comments

Post a Comment