A Murder in Blackman Mine

In 1895, after falling in love with the wife of the owner of the Wilkes-Barre boarding house in which he was living, a 28-year-old miner named Anthony Zemartis thought he had conceived the perfect crime.

Andrew Yiesti was a quiet and attractive 35-year-old Lithuanian man who, along with his wife, kept a boarding house at 17 Murray Street. In early 1895, a new boarder moved in, and he immediately became enamored with Andrew's 25-year-old wife. Over the course of the spring and summer, the friendship between Anthony Zemartis and Annie Yiesti grew intimate. Even the husband could figure out that something shameful was taking place under his very nose, but Andrew was too mild-mannered and reserved to say anything about it.

As time wore on, Annie and Anthony's affair was displayed with less secrecy, and it soon became obvious to the lovers that it was now necessary to do something about Mr. Yiesti. Annie devised a plan. In early June, she appeared before Mayor Nichols and swore out a warrant for her husband's arrest, alleging that he was frequently drunk and abusive. At the hearing, Zemartis offered testimony against Yiesti, but the case was dismissed after another boarder came forward and spoke of the affair between Annie Yiesti and Zemartis.

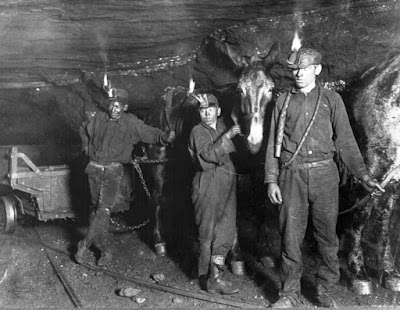

As awkward as it may have been, Yiesti and Zemartis not only lived under the same roof, but also worked together in the Blackman mines. It was deep in the mine, hundreds of feet below ground, where Zemartis devised his plan to get rid of his lover's husband once and for all.

On the morning of Friday, June 14, the two men left the house on Murray Street and arrived at the mine for a 12-hour shift at six o'clock in the morning. At six o'clock in the evening, only one of the men emerged from the mine.

Upon leaving the mine, Zemartis ran up to a pump runner and told him that a terrible accident had taken place-- Andrew Yiesti had been killed by a fall of rock following an explosion. The pump runner went for help while Zemartis stayed with the body, and when the company ambulance arrived, the dead man was taken to his home. The widow displayed a great deal of anguish and grief, but the boarders paid little attention to the corpse. They knew all about the affair, and automatically suspected Zemartis of foul play.

Annie immediately went to the undertaking establishment of Danksza and Sesniewicz on East Market Street and paid the undertakers to take charge of the body at once. This seemed strange to Sesniewicz, who noticed that Annie seemed to display very little sorrow. While most grieving widows wanted to stay close to the remains of their husbands, Mrs. Yiesti spoke of her dead husband as if he were a week-old bag of rotting trash. When the undertaker arrived at the house on Murray Street, his suspicions grew deeper. Annie insisted that her husband be buried in the work clothes he was still wearing, claiming that she couldn't afford a proper suit.

When the Sesniewicz returned to his undertaking establishment with the body, he examined the corpse, which was covered in ghastly burn marks, and something seemed out of the ordinary. He spoke to the chief of police, who advised him to find a physician. The following afternoon, Dr. Warnagiris arrived at the undertaking parlor to view the body, and he made a startling discovery-- the doctor discovered four bullet wounds, proving that Andrew Yiesti had been shot from behind.

Authorities now had enough information to put together a theory of what had happened to Andrew Yiesti. After shooting his victim, Zemartis had used his lantern to burn the body in an attempt to conceal the bullet wounds, then covered the corpse with coal. The undertakers, along with police, refused to divulge this information. They had a plan, but in order for their plan to succeed, the body had to be prepared for burial and a viewing had to be held at the dead man's home on Murray Street.

The following afternoon, after the body was laid out and the mourners let into house, Sesniewicz dispatched a messenger to Tuck's Drugstore, where the police were notified. Sesniewicz, Danksza and Dr. Warnagiris did their best to prevent the mourners from leaving the house. As a ruse, the undertakers claimed that the funeral could not take place until a city official arrived with a permit.

At 4:30, Chief Briggs arrived with a patrol wagon and a squad of officers. They surrounded the house and Briggs went inside and arrested the occupants. Annie Yiesti, Anthony Zemartis, William Zemartis, John Orbein, and Peter Scuville were taken into custody and transported to the police station. After questioning, Orbein, Scuville and William Zemartis were released, while Annie and her lover were jailed.

With the suspects in custody, police searched the Yiesti house and found a box of .38-caliber bullets in Zemartis' room. They matched the bullets taken from the dead man's body. After looking into the alleged killer's past, authorities learned that Zemartis had been suspected of murdering a man in New York before he arrived in Pennsylvania.

Despite the strong case against the miner's widow and her lover, a series of complications prevented justice from being served. In December, Annie and Anthony were released from jail. Two terms of court had passed and the defendants had still not been brought to trial; under the law, they could not be held any longer. If they were ever to be brought to justice, they would need to be re-arrested. The following day, a local justice of the peace issued warrants for their arrest, but the defense attorney, James L. Lenahan, claimed that since the defendants had been previously arrested on the same charge and released, it was a classic case of double jeopardy. Lenahan's objection was overruled, and a trial date was set.

In January of 1896, Anthony Zemartis was convicted of first-degree murder and sentenced to death by hanging. Annie Yiesti was acquitted. However, the case was appealed and after a re-trial in April, a jury found Zemartis not guilty of the murder.

The grounds for the re-trial arose from a peculiar incident that took place not in Luzerne County, but in the mining town of Shenandoah in Schuylkill County. Six months earlier, a miner named Frank Kunza was arrested by borough constable Matt Giblon, on the charge of stealing a watch from a fellow boarder. The theft victim went to the police with a remarkable story, claiming that Kunza had once admitted to killing a man over a year earlier near Wilkes-Barre. Kunza, who was employed at the Blackman mine at the time and was living at the boarding house on Murray Street, had also begun having an affair with Annie Yiesti. Determined to do away with his paramour's husband, Kunza shot Andrew Yiesti in the back and buried the body under a pile of coal. Upon learning that another co-worker, Anthony Zemartis, had been arrested for the crime, Kunza fled to Shamokin, where he worked for a short time before moving to Shenandoah.

While Wilkes-Barre police dismissed the story as a hoax perpetrated by an enemy of Frank Kunza, it created enough reasonable doubt among the jury to result in Zemartis' acquittal, and the accused killer left the Luzerne County courthouse laughing.

So who really murdered the mild-mannered Lithuanian miner? The truth will probably never be known.

Comments

Post a Comment