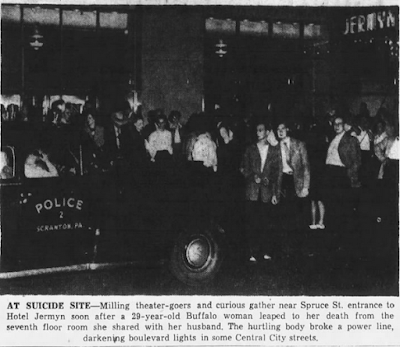

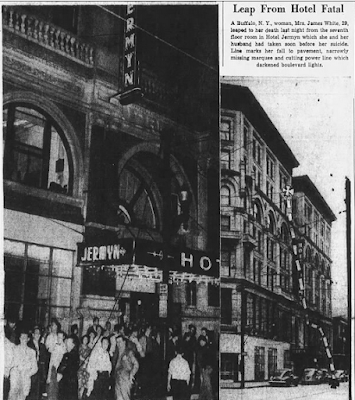

Ethel White's Plunge to Death

Built in 1894, the seven-story Hotel Jermyn building has been a Scranton landmark for over a century. Named after immigrant coal baron John Jermyn, the 200-room hotel has seen scores of famous and infamous guests alike, from President Eisenhower to mafia hitmen, and has boasted a bevy of locally-famous bars and nightclubs such as the Omar Room, which opened in 1935 and showcased renowned performers of the era like Pauline Gaskins, Manfred Gotthelf, Scotty Burbank, Frank Fay and Red Nichols.

Today, the Scranton landmark once known as the Hotel Jermyn now operates as an apartment building for those ages 55 and over. Perhaps some of the older residents may remember dancing the night away in the hotel's Arabian Ballroom, slaking their thirst in the Manhattan Bar, or lunching at the Purple Cow Restaurant. And perhaps some of them might still recall that night in 1947 when a young woman named Ethel White mysteriously jumped to her death from her seventh floor window.

At eight o'clock on the evening of Thursday, August 21, a married couple from Buffalo, New York, checked into the Hotel Jermyn after a long drive from Albany. The husband was James O. White, a salesman for a Baltimore-based Burns Bottling Machinery Company; the woman was his 29-year-old wife, Ethel. Their three-year-old daughter, Barbara, had remained in Buffalo, left to the care of a neighbor until their return. Upon the hotel guest register they signed their names, listing their home address as 254 Blain Avenue. En route to Washington, D.C., the Whites planned to spend the night in Scranton, and, after checking into their room on the seventh floor, room number 724, James attempted to telephone an old friend from Scranton to tell him that he was in town.

Unable to reach his friend by phone, James told his wife that he would probably find him at the Hotel Casey, and he left the room at about 8:30, promising to be back soon. "Goodbye," said Ethel, with an odd inflection in her voice. He asked her why she had said goodbye in that manner, but Ethel insisted there was nothing odd about the way she had said it. "Would you like to go with me?" he asked, wondering if perhaps she had felt snubbed. Ethel replied in the negative.

He drove to the Hotel Casey and located his friend, who agreed to a late dinner with James and Ethel that evening at eleven o'clock. James White drove back to the hotel and parked in the rear of the building at approximately 8:55. As he walked around the the Spruce Street side of the hotel, he found the sidewalk jammed by a large crowd of shadowy faces; although he did not know it at the time, power had been knocked out to the entire 300, 400 and 500 blocks of Spruce Street.

A Mysterious Face in the Window

Ben Lonstein, of 211 Arthur Avenue, was walking to his car which was parked along Spruce Street when the entire city of Scranton seemed to go dark. The lights had gone out in the Electric City, it seemed, and when Ben reached his car at 8:30 that evening he was chagrined to discover that a fallen power line had created a hole in the body of his automobile. He spotted a policeman on the corner, Patrolman Joseph Scanlon, and angrily stormed in his direction to register a complaint. Just a moment earlier, Harold Ottaviani, of 172 North Ridge Street in Tunkhannock, was standing on the corner of Spruce Street and Wyoming Avenue talking to Patrolman Scanlon when he was struck on the right temple by a falling piece of glass insulator. Patrolman Scanlon too was struck by the glass, and was bleeding heavily from a gash in his hand when Lonstein reached him.

A moment before any of this occurred, Eugene Tedesco, of 325 Oak Street in Peckville, was standing on the corner of Wyoming and Spruce, across from the Hotel Jermyn, waiting for a bus. Something-- perhaps boredom-- compelled him to glance upwards, just in time to see an object plummeting from the upper floor of the building. Tedesco immediately recognized the falling object as a woman. Paralyzed by horror, he watched the body strike a telephone wire before landing with a sickening thud in the center of Spruce Street, midway between the trolley track and the curb.

"As I started to run across the street, I remember thinking that pedestrians walking near the hotel did not seem to realize what had happened," Tedesco told reporters. "People were scurrying towards the Purple Cow Restaurant as if they feared a portion of the hotel roof was falling.

"While crossing the street, I heard a heavy dull thud. I think I was the first one to actually know what had happened, and I was the first on the scene," he continued. "When I reached the woman, she was lying on her left side, her face resting with the left cheek on the ground. Her left arm was twisted under her body. As soon as I saw the body I said to myself, 'she is dead.' I don't know how my attention was attracted to the falling body because I don't recall hearing any screams or shouts. I remember that when I looked upwards, I saw a head in a window, but I'm not sure whether the person was in the same room that the woman fell from."

Eugene Tedesco had just witnessed one of the most horrific sights that human eyes could behold, so he could be forgiven if he couldn't remember whether the mysterious face he saw in the window had been that of a man or a woman, or if he had seen the face in the window of Ethel White's hotel room or in the window of a different room altogether. It certainly could not have been the face of James White, who was parking his car at the time his wife fell to her death. This detail was one of many peculiar details surrounding the death of 29-year-old Ethel White.

|

| The Hotel Jermyn, now an apartment complex, as it appears today |

A Mysterious Note

When James White approached the crowd in front of the hotel, he pulled a man aside from the throng of spectators and asked what had happened. He was told that a woman had jumped from a window. Having no interest in the ghastly spectacle, he elbowed his way through the crowd and into the hotel lobby, where he asked the clerk for the key to his room-- Number 724. The clerk, who by this time was aware of the fact that it was from room number 724 from which the woman had jumped, grew panicked and summoned the hotel manager, Thomas Ryan. It was Ryan who broke the news to James White.

White immediately telephoned his friend at the Hotel Casey, who rushed to the Jermyn and drove White and Sergeant Emil Zurcher of the Scranton Police Department to the hospital. By this time, the hospital had been able to establish the identity of the deceased woman, though her age had been listed as 35, and her address had been listed as 2229 Kirk Avenue in Baltimore. White was perplexed by this error, and said that he recognized the address as being that of his employer. But things became even more mysterious when police produced the suicide note which Ethel had reportedly left in her room.

I've been so wrong about everything, read the strange handwritten note. The word "every" had been underlined in heavy ink.

White identified the handwriting as that of his wife. He also identified the body, but explained that his wife was 29 years of age, and that they had signed the hotel guest register with their correct address-- 254 Blaine Avenue, Buffalo, New York. How could such a mix-up occur when the facts were so readily available? And with the exception of James White and possibly his wife, who could possibly know the address of the Burns Bottling Machinery Company in Baltimore? Even if one of James' business cards had been found inside the hotel room, it would have been obvious that it was not a residential address listed on the card.

James White cooperated fully with the police investigation, but could offer no insight into the cryptic suicide note. Ethel had been in her usual spirits when they left Buffalo on the night of Tuesday, August 19, and drove to Auburn, and from there on to Albany, before heading to Scranton. They were planning to buy a house in the Washington area so that James could be closer to his work. He told police that his wife's parents resided in Lackawanna, New York, and that their young daughter, Barbara, had been left in the care of friends back in Buffalo. White's career prospects seemed promising and the future appeared bright for the couple. Though they had been married six years, they were still in the summer of their youth. Ethel had never shown any previous signs of mental illness. As far as anyone could tell, there was no reason for Ethel White to take her own life.

Yet suicide was the conclusion reached by Dr. Martin Chomko, chief resident physician at the city hospital and deputy coroner of Lackawanna County. Her injuries included a fractured skull, a fractured pelvis, a broken arm, and her chest was completely caved in when she struck the pavement. She had been fully clothed when she jumped.

A ladies wristwatch found on Spruce Street had also been positively identified by James White as belonging to his wife. The watch was stopped at 8:30, indicating that Ethel White had leaped from her hotel room window immediately after her husband had left to visit his friend at the Hotel Casey. In other words, assuming that the watch hadn't been thrown out of the window before Ethel's death, James White was presumably the last person to see her alive.

Was it his face that Eugene Tedesco had seen in the window just after the young woman's body hit the street?

Police didn't seem to have an interest in this line of questioning; James had an airtight alibi and a friend who could vouch for his whereabouts, and Dr. Chomko's verdict was accepted without question by Superintendent of Police Leo Ruddy, who was in charge of the investigation. The body of Ethel White was prepared for burial at the Cusick Funeral Home at 217 Jefferson Avenue and shipped back to Buffalo aboard a Lackawanna Railroad train.

And that, it seems, is where the story ends. Newspapers from the Buffalo area made no mention of Ethel White or her demise, and the trail of James O. White seems to have disappeared from that day forward as well. The cryptic suicide note only adds to the intrigue; what was it that Mrs. White had been so wrong about? Did she discover that her husband was leading a double life? Or maybe it was the other way around. Maybe she had accused James of some infidelity that later proved to be untrue and, perhaps devastated and ashamed, she leaped to her death. Or perhaps Ethel White was the one who had been leading a double life-- other than her suicide jump, there seems to be no record of her... not in the U.S. census, no marriage records, no birth records, no burial records. Was she using an alias? Was she alone when she fell from the window of the Hotel Jermyn? Was the eyewitness, Eugene Tedesco, mistaken about the face he saw in the window?

Perhaps this is why the story of Ethel White's suicide leap from the seventh floor of the Hotel Jermyn still captures the imagination nearly three quarters of a century after it happened.

Sources:

Scranton Times-Tribune, Aug. 22, 1947.

Scranton Tribune, Aug. 22, 1947.

Scranton Tribune, Aug. 23, 1947.

I have found a James White age 26 and Ethel White age 22 living at 160 Randolph Street in Buffalo NY in the 1940 census via ancestry.com. His job is listed as legal investigation and hers as file clerk, apparently at the same company which is just listed as "corporation counsel's office." Also found her death certificate on ancestry.com if you're interested in seeing either of those things.

ReplyDeleteI live at Hotel Jermyn and my bedroom window is the window that Ethel White jumped out of on the night of her tragedy. I was going through the history of Hotel Jermyn as i usually do because that is a reason i wanted to move here. I came across this article last month. I asked about room 724 because I live on the 7th floor and was told there was no room 724. It turns out the numbering of the rooms changed and the layout marks directly out of my bedroom window. I'd appreciate information about Ethels history. I'm also trying to do some research myself now

DeleteI would like to see the Death Certificate. My podcast “Slice of the Paranormal” is going to do an episode where we talk about the Hotel Jermyn

Delete