Gilbert E. Gable: From the City of Shamokin to the State of Jefferson

In the summer of 1929, in the sun-scorched Arizona canyons, a special ceremony was being held on the Navajo reservation about 75 miles north of Flagstaff. It was a historic moment; never before had a white man been "adopted" by the ancient tribe, but on this day two men would be bestowed with this honor. The second man, W.A. Detweiler, was a newspaperman from Philadelphia. The first white man to be adopted by the Navajo was Detweiler's brother-in-law, Gilbert Elledy Gable-- movie producer, entrepreneur, adventurer, dinosaur hunter, exotic fruit inventor, governor of an imaginary state, and perhaps the most eccentric native in the history of Shamokin, Pennsylvania.

To say that Gilbert E. Gable was a man of varied interests is an understatement. No matter where in the world he traveled, tales of his zany (and occasionally controversial) exploits always found their way back to Northumberland County. Local papers, for instance, reported on Gable's extensive travels through the Southwest in the 1920s, where he cultivated, according to the Shamokin News-Dispatch, "a new fruit that he believes some day will grace the American breakfast table". This fruit, a seedless orange-grapefruit hybrid, was cultivated by Gable on a farm in Texas, and although the results were, by all accounts, rather disappointing, this setback did not dampen Gable's spirit. Within a few short months he would turn his attention to relic hunting in the famed "Dinosaur Canyon" near Tuba City, Arizona, and find himself a central figure in one of the biggest paleontological controversies of the era.

Decades later, however, Gable would attain his greatest level of fame-- as the man behind the crusade to create a new state in the Pacific Northwest known as the State of Jefferson.

|

| The Gable home in Shamokin as it appears today |

The Early Life of Gilbert Gable

Born in Shamokin in 1886, Gilbert was the youngest of four children born to Martin Luther Gable and Jennie Pricilla Gable. Gilbert's father operated a shoe store on Independence Street, while both of Gilbert's brothers found success in completely different fields; one became the operator of a chain of gasoline stations in Virginia, while the other became a renowned physicist.

As a young man, Gilbert relocated to Wilkes-Barre and worked as a collector for the Bell Telephone Company, which paid the bills but did little to satisfy his craving for life in the public eye. In his spare time he studied advertising and began tinkering with advertisements and slogans for his employer, largely for his own amusement. Somehow, these got back to the company headquarters and the Bell Telephone executives were so impressed that they promoted Gable to advertising department in Harrisburg. He soon relocated to Philadelphia, where he married his first wife, Hazel Detweiler, in 1915. The outbreak of World War I, however, gave Gable a chance to indulge his creative side after he was named publicity manager for the Liberty Loan Drive in Philadelphia, which sold war bonds to support the Allied cause.

Motion pictures appealed to Gilbert, whose love of showmanship and knowledge of electronics and technology made him a natural fit for the fast-growing industry. Before Hollywood, the east coast was the center of the film industry (Thomas Edison's motion picture studio, the first movie studio in the world, was based in New Jersey and later Manhattan), and by the early 1920s Gilbert had started his own company, Achievement Films, Inc., and had found a small measure of success as a filmmaker. His 1923 silent film, Slave of Desire, was distributed by Goldwyn Pictures and hailed by critics as one of the year's best pictures; a young Bessie Love, cast as the female lead, would be nominated for an Academy Award six years later and would eventually earn a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.

As Gilbert's career flourished, he never turned his back on his hometown and made frequent visits to Shamokin. These trips became more frequent after his father passed away in 1920, leaving Jennie Gable a widow struggling with arthritis and other chronic illnesses and living alone at the family home at 23 East Independence Street. She continued to live in the same house at the corner of Cleaver and Independence streets until her death in 1938 at the age of 91. Though her other children returned to Pennsylvania to visit whenever they could, Gilbert's independence as a entrepreneur permitted him to come to Shamokin frequently, though he always kept a low profile during these trips despite his budding fame and success. It seems he wanted his mother to be the "star of the show", and she often was-- at the time of her death, Jennie was one of Shamokin's oldest and most esteemed residents.

Movie Producer Turned Adventurer

While in Brookline, Massachusetts, in December of 1926, Hazel Gable passed away at the age of 40. Although the manner of her death was not disclosed to the public, the unexpected death had an indelible effect on Gilbert. He devoted more of his time to his other interests, which included everything from cave exploration to amateur archaeology. In 1927, Gable, now vice-president of Bray Pictures Corporation, married his love of film with his love of adventure in an undertaking the Los Angeles Times described as "one of the most hazardous undertakings ever attempted for the filming of a motion picture". For this film, Menace, Gable enlisted the aid of the National Geographic Survey and the Army Signal Corps and headed to the north rim of the Grand Canyon with a camera crew to film Major E.C. LaRue's 796-mile boat expedition on the Colorado River from Green River, Utah, to Needles, California.

Gable's fascination with natural history and the West led to a friendship with Charles J. Rhoades, the U.S. Commissioner of Indian Affairs. The following year, Gable and Rhoades collaborated on the National Broadcasting Company's radio series Adventures on the Highroad, which presented an intimate glimpse of life among the Hopi and Navajo peoples of Arizona. Gable's charming personality made him a favorite among the latter, which led to him being adopted as a member of their nation in 1929-- and also led to one of the biggest battles in Gable's career.

Early in 1928 a Navajo guide led Gilbert to a remote canyon which, until that time, had never been explored by a white man. The Navajo guide, aware of Gable's interest in natural history, wished to show his friend some strange "turkey tracks" he had found, and Gable immediately recognized these as dinosaur footprints. He returned to Philadelphia in a state of high excitement and convinced the Museum of Natural History and the University of Philadelphia to mount a joint scientific expedition near Tuba City, Arizona.

It was here, in what would later become famous as "Dinosaur Canyon", where Gable's expedition uncovered several hundred preserved dinosaur tracks beneath an 8-inch layer of stone. Important paleontological finds from this 1929 expedition include the largest dinosaur footprint ever discovered and the skeletons of several extinct species which had heretofore been unknown to science. Within twelve years, Gilbert E. Gable had gone from working as a telephone company bill collector, to producing feature films for Goldwyn-Mayer, becoming an honorary Navajo, and making groundbreaking scientific discoveries. Not too shabby for a kid from Shamokin.

However, Gable's adventurous lifestyle was not without its setbacks and controversies.

Gable drew the ire of Arizona governor John C. Phillips over his dinosaur track discovery, causing the governor to dispatch deputy sheriffs to Dinosaur Canyon to prevent a team of scientists from removing prehistoric specimens. Having learned that Gable's party intended to transport the relics to museums in the east without securing a permit, Gov. Phillips ordered the lawmen to put a stop to the expedition. He accused Gable and his team of vandalism and other baseless charges. He then appealed to the Secretary of the Interior for the federal government to intercede.

Gable fired back at Phillips. "I am in entire sympathy with the governor in his desire to preserve the priceless historical and archaeological treasures of this state," said Gable, "but I am surprised that the governor, with his knowledge of the personnel of this expedition, representing as it does the leading institutions of the nation, apparently was unable to distinguish between the vandalism of curiosity hunters and the efforts of scientific men." He described the governor's actions as "careless acts" that hindered serious scientific study, and added that he had broken no laws, and had secured the necessary permissions from Superintendent C.L. Walker of the Navajo Indian Agency.

For weeks, Governor Phillips and Gilbert Gable traded shots in the national papers. Gable embarked on a speaking tour defending his position, and these lectures, along with the popularity of his NBC radio program chronicling his finds in the Arizona desert, put public sentiment largely on his side. But Gable was not the type to rest on his laurels; while the governor continued to fume, Gable and fellow expedition member Freeman R. Stearns, who was a noted aviation expert, announced plans to build a glider factory in California.

Unfortunately, Governor Phillips put the kibosh on Gable's plans for future expeditions in a rather diabolical and vengeful manner by creating a state archaeological commission, which granted permits to geologists, paleontologists and archaeologists to dig in the Arizona desert. While this commission readily issued permits to every charlatan and huckster with a shovel, every one of Gable's permit applications was denied. Proof of Phillips' childish antics came to light in 1930, after the chairman of the governor's own archaeological commission, Dean Byron Cummings, published a letter he had written to the governor on behalf of Gable, urging Phillips to allow Gable permission to resume his work at Dinosaur Canyon. In his letter to the governor, Cummings wrote:

We are in receipt of the copy of Mr. Gable's letter to you. We have recommended that the American Museum be granted a permit to continue their investigations of dinosaur tracks and collect paleontological specimens in Northern Arizona.

Phillips refused to change his mind, but, by this time, Gilbert E. Gable had turned his attention to other projects. Before long, he would enter the political arena himself, and secure his place in American history as the founder of a breakaway state in the Pacific Northwest.

A New Frontier

On May 30, 1931, Gable surprised many by marrying Paulina Stearns, the sister of his partner in the aviation business, in a secret ceremony at the Vassar Club in New York. Only Gable's immediate family knew about the engagement, and the only persons present at the ceremony were the officiating pastor, Rev. Sockman, and Myra Langdon, a college friend of the bride. Society columns in papers across the country spilled gallons of ink writing about the "secret ceremony" between the daughter of prosperous Michigan lumberman Col. J.S. Stearns and the wildly popular radio personality, who, by this time, had traded his image as a Hollywood movie producer for that of an Indiana Jones-like adventurer.

|

| Gilbert Gable (left), with Paulina Stearns and Freeman Stearns |

After the ceremony, Paulina left Michigan and moved to New York to rejoin her new husband at the Hotel Lexington, where he resided. By 1934, Gable, with the help of his father-in-law, had acquired tracts of land in Oregon which he planned to develop for timber and mining purposes, and in June of that year the Gables departed from Ludington, Michigan, to the Pacific Northwest, accompanied by a bevy of mining engineers.

The Gables settled in Port Orford in the southwest corner of Oregon, and it wasn't long before Gilbert turned his attention to improving conditions in that rugged and sparsely-populated part of the state. He threw himself into civic causes while, at the same time, managed to oversee the daily operations of six companies engaged in "modernizing" the region and developing ports along the coastline. Of course, his actions were more out of concern for his personal interests than pure altruism; his construction of a 500-foot breakwater dock allowed his Trans-Pacific Lumber Company to ship two million feet of timber monthly. By 1936, his company was shipping 125 million feet of timber annually, with most of the timber headed to buyers in Japan.

Nonetheless, Gable had big visions for the tiny village of Port Orford, which had a population of just 300 at the time. Gable envisioned a connection with the Gold Coast Railroad, which would allow his mining company to transport chromium ore to the port he had built. He envisioned other sources of commerce for the fledgling community, such as commercial fishing and agriculture. He even entertained the possibility of utilizing his port facilities as a harbor of refuge for naval vessels, insisting that Port Orford, flanked by the Humbug Mountains, offered the ideal place for the entire Pacific Fleet to drop anchor.

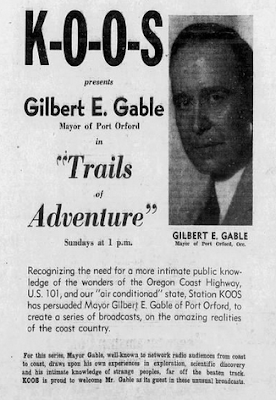

Gable was instrumental in the creation of the Coos-Curry County Chamber of Commerce in 1937, and it was only natural that he should become the mayor of Port Orford and the rehabilitation commissioner for the nearby town of Bandon. Still brimming with the patriotism and promotional prowess he had displayed during the Liberty Loan drives of World War I, Gable threw himself into his new role as spokesperson for the citizens of southwest Oregon, whose needs, he believed, were woefully ignored by state government. He crusaded for better roads, schools, and telephone service and was determined to modernize Curry County and turn it into a thriving economic powerhouse. He was so determined, in fact, that he very nearly succeeded in breaking away from Oregon and forming a brand new state.

Secession Threatened

The tiny village of Port Orford flourished during Gable's tenure as mayor, and its population more than doubled between 1930 and 1940. In 1939 he purchased Port Orford's weekly newspaper after the death of longtime publisher Frank Faye Eddy and actively promoted the mining of chromium, manganese and other valuable minerals in Curry and surrounding counties. Unfortunately, the poor condition of rural roads and highways prevented Port Orford from attaining the type of economic prosperity Gable had envisioned. In June of 1940, Gable called upon thirty mayors of southwestern Oregon towns to travel to Port Orford for an "emergency summit" to initiate action. The weekend-long conference was serious business to Gilbert E. Gable, but he reeled in his guests by treating them to a fishing trip and an afternoon of panning for gold on Sixes River.

Declaring that miners and ranchers living on southwestern Oregon were "the real forgotten men" of America, Gable presented a petition to the Coos County court in December proposing the construction of a seven-mile road that would connect to the Grants Pass highway that was presently under construction. Gable believed that the CCC should build the road, but was seeking assurance from Coos and Curry county officials that they would maintain it. When this plan failed, Gable took a bold step: He threatened secession.

Gable declared that if the state continued to neglect the residents of southwestern Oregon, he would allow California to "annex" Curry County from Oregon. In October of 1941, he directed the county court to name a special commission to explore the legalities of secession. Meanwhile, he sent a letter to the governor of California, Culbert Olson, asking for a meeting to discuss his idea. In his plea to Olson, Gable accused Oregon of failing to develop his state's vast mineral resources, and suggested that California might have an economic interest in the region's mineral wealth. He provided the findings of geological assays he had funded out of his own pocket showing the governor that thousands of tons of chromite, manganese, cadmium, molybdenum, beryllium, copper and nickel were present in Curry County and could easily be mined if only someone would build a road.

To the astonishment of many, Governor Olson agreed to meet with the delegation from Curry County on October 31, 1941. This group consisted of Gable, Elmer Bankus and attorney Collier H. Buffington. Governor Olson was amenable to the idea, but told the secessionists that they would first need to obtain Oregon's approval. "We feel highly complimented you would want to join us," Olson told the secessionists, but you wouldn't want the governor of California to go out in conquest after a piece of a neighbor state, would you?" The meeting was quite entertaining; a group of five men from Oregon dressed up like cavemen crashed the summit to protest Gable's plan.

The State of Jefferson

Gable was undaunted by Governor Olson's refusal to annex Curry County without the cooperation of Oregon, so the secessionists formulated a new plan. If they couldn't obtain permission for Curry County to abandon the state of Oregon, maybe they could convince some counties in northern California to join forces with them and form an entirely new state.

This audacious plan appealed to Randolph Collier, a state senator from Siskiyou County, California, who had similar complaints regarding the poor condition of highways in his district (Collier served as chairman of the California Senate Transportation Committee). Siskiyou's county seat, the city of Yreka, was the proposed capital of the proposed state, which the secessionists named Jefferson in tribute to the president responsible for the Lewis and Clark Expedition. The movement quickly gained followers, and by the end of November, the proposed State of Jefferson would include the Oregon counties of Curry, Josephine, Jackson and Klamath as well as the California counties of Del Norte, Siskiyou and Modoc (interestingly, if this plan would've worked, the State of Jefferson would currently rank 33rd in population and 14th in total area, making it more populous than Nevada and larger than Idaho).

While many believed that Gable and his supporters were not serious and had merely been attempting to demonstrate a point, others were more militant in their support for the State of Jefferson. On Thursday, November 27, 1941, a group of secessionists acting as ersatz "border patrol" agents, stopped traffic heading into Yreka and handed out handbills which read: You are now entering Jefferson, the forty-ninth state of the union. Jefferson is in rebellion against the states of California and Oregon. This state has seceded from California and patriotic Jeffersonians intend to secede each Thursday, until further notice. The other six days of the week, the secessionists said, they would identify as Californians.

|

| Flag of the proposed State of Jefferson, probably designed by Gable himself. |

The End of the Road

The State of Jefferson movement fizzled out just as it seemed to be making progress, and the primary reason for this was the unexpected death of the movement's founder, Gilbert E. Gable. On the morning of December 2, 1941, Gable died at his home in Port Orford after an attack of "acute indigestion". Gable, who was 51 at the time of his death, was in his third term as the town's mayor.

His body was transported to Ludington, Michigan, for burial at the Stearns family mausoleum at Lakeview Cemetery. His wife, Paulina Stearns Gable, split her time between Michigan and the winter home she and Gilbert had built near Tucson with their son, Robert. Sadly, local papers devoted just a few sentences to Gilbert's death, though very few natives of Northumberland County can claim to have crammed as much life into a half century as Gilbert E. Gable, who did everything from making feature films for Goldwyn-Mayer to hosting a popular radio show on NBC, to making groundbreaking discoveries in paleontology, discovering the famous Dinosaur Canyon in Arizona, and convincing seven counties in Oregon and California to secede from their respective states.

While most of Pennsylvania has forgotten the name Gilbert E. Gable, his legacy lives on in the Pacific Northwest, where a new push to create the State of Jefferson crops up every few decades, the most recent of which occurred after the 2016 presidential election. In 1989, a public radio station based in Jackson County, Oregon, rebranded itself as "Jefferson Public Radio", as its broadcast signal could be heard in most places that would've been part of the breakaway state.

Gable's vision is also commemorated by a 109-mile stretch of highway between Yreka, California, and O'Brien, Oregon, designated as the Jefferson Scenic Byway. In a strange way, this seems to suggest that Gable ultimately won his battle; in 1940 he had fought for a 7-mile stretch of crudely-paved road, and succeeded in getting 109 miles of State Route 96.

Sources:

Philadelphia Public Ledger, Oct. 11, 1915.

Allentown Morning Call, Dec. 16, 1923.

Los Angeles Times, Nov. 12, 1927.

Shamokin News-Dispatch, July 17, 1929.

Los Angeles Times, Nov. 21, 1929.

Wilkes-Barre Record, Nov. 23, 1929.

Los Angeles Times, Dec. 5, 1929.

Arizona Republic, June 16, 1930.

Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Nov. 9, 1930.

The Journal (Meriden, CT), Nov. 18, 1930.

Ludington Daily News, Aug. 18, 1931.

Ludington Daily News, June 21, 1934.

Coos Bay World, Nov. 9, 1935.

Coos Bay World, May 18, 1937.

Shamokin News-Dispatch, June 17, 1938.

Coos Bay World, June 21, 1940.

Coos Bay World, Dec. 3, 1940.

Coos Bay World, Oct. 13, 1941.

Corvallis Gazette-Times, Oct. 31, 1941.

Klamath Falls Evening Herald, Oct. 31, 1941.

Medford Mail Tribune, Nov. 28, 1941.

Salem Statesman Journal, Nov. 28, 1941.

Salem Capital Journal, Dec. 2, 1941.

Arizona Daily Star, Dec. 3, 1941.

Comments

Post a Comment