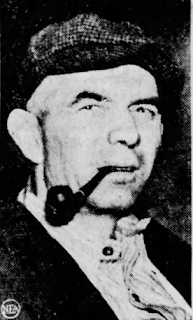

Portrait of an Executioner: Frank Lee Wilson

On a crisp October day in 1939, a thin man in wire-rim spectacles left his mother's house on Ellis Avenue in Pittsburgh and traveled across the Allegheny Plateau to his new job in Centre County. Quiet and soft-spoken with a receding hairline, 37-year-old Frank Lee Wilson looked like the nondescript, timid sort of man whose job might be that of an accountant, or perhaps a high school science teacher. In fact, once upon a time Frank Lee Wilson did teach electrical engineering classes at a local vocational school, but his new workplace was a far cry from the classrooms of South High School . His new employer was Rockview Prison in Bellefonte, which, at the time, was a branch of the Western Penitentiary. His talents as an electrician would prove indispensable in his new role as the first official executioner for the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania.

The story of the rise and fall of Frank Lee Wilson is a remarkable tale; it is the tragic story of a quiet, tiny man tasked with the awesome responsibility of meting out justice to the state's most hardened and repugnant criminals. And it is a cautionary tale about how a mild-mannered individual can turn into a cruel, hardened shell of a human being in just a few short years after being granted the God-like power of revoking human life.

The Warden and Mr. X

It was July of 1938 when Warden Stanley P. Ashe offered Wilson the position as Mr. X, which, for the sake of anonymity, had long been the unofficial name of the man who flipped the switch of Old Sparky, the state's infamous electric chair. Although Wilson would become the state's first full-time executioner, several different men had filled the role of Mr. X since the first convict was executed by electrocution in Pennsylvania in 1915. In those days, executioners traveled from state to state plying their grisly trade, and the man Wilson was replacing, Robert Elliott, was a legend in the annals of capital punishment.

Elliott, who expertly executed 387 prisoners in Pennsylvania and neighboring states during his career-- more than any other American executioner-- had been mulling over retirement for quite some time due to health reasons, but continued to perform his job until Warden Ashe could find a suitable replacement. Frank Lee Wilson had attracted the warden's attention while supervising the installation of a new lighting system at Pittsburgh's Western Penitentiary. The project took two years to complete, and during this time Wilson and the warden had developed a close friendship.

Wilson, however, was hesitant to accept the position as Robert Elliott's successor. Perhaps he was aware of the jinx that plagued Pennsylvania's previous executioners; this first man to pull the switch at Rockview was Maurice Broderick, who racked up 166 executions before being crushed to death by a crane at the age of 37 while supervising a prison construction project in 1926. There was Sylvester McNeal, one of the early traveling executioners, who died of a heart attack in the warden's office after performing an electrocution in Ohio, and John Hulbert, who shot himself in the head in 1926. There was Edward Davis, who grew so disgusted by his work that he quit abruptly one day and lived the rest of his life in solitude as a hermit. Of the amateur Rockview executioner who electrocuted wife slayer Mike Louisa in 1916 not much is known, other than he was an engineering student at Penn State University who was called upon to "pinch hit" for Maurice Broderick.

Even the legendary Robert Elliott had seen his house blown up in 1928 after he pulled the switch on anarchists Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, which required a police booth to be erected in his yard with an officer to guard him until the day of his death. It was around this time he suffered a nervous breakdown after pulling the switch on a female prisoner, and friends and colleagues observed that he was never the same man ever again. Shortly before his death on October 10, 1939, Elliott became an outspoken critic of the electric chair. "It doesn't do any good," he said repeatedly. "There is a certain satisfaction the state gets, a sort of revenge. But we keep on getting these terrible criminals just the same."

It is understandable why Frank Lee Wilson needed some time to make up his mind.

Nevertheless, Wilson accepted the position, which paid $250 per single electrocution and $100 for any additional execution performed on the same day. As part of the agreement, Wilson was permitted to keep his regular job at the Raphael Electric Construction Company. On the night of October 23, 1939, arrived at Rockview neatly-dressed in an oxford gray pinstripe suit, white shirt and blue and white tie, and he would return home to his mother, wife and two children the next day $450 richer.

Duck Hunter Turns Overnight Celebrity

Wilson did not have the luxury of easing into his new role. Just as soon as he was hired he was called upon to perform a triple execution, and the rookie executioner took his place behind the switch at 12:31 and calmly and coolly dispatched his victims in under fifteen minutes. The first prisoner that day was Paul Ferry, who had slaughtered his wife three years earlier with an axe inside their Erie home. With three flips of a switch Wilson sent 2,000 volts of electricity into Ferry's body, but it was evident that Wilson lacked the finesse of his predecessor. According to reports, Wilson applied the first jolt ten seconds longer than was the custom, which caused "smoke to mushroom from the prisoner's head" and the body to break out in blisters-- Ferry had been cooked well beyond the 240-degree electrocution temperature. However, Wilson refined his technique and flawlessly electrocuted Willie Bailey and Ira Redmon by 12:46.

|

| Paul Ferry, Wilson's first execution |

After the task was complete, Wilson lit a cigarette and chatted with Warden Ashe, who invited Wilson to his home for dinner that night, where he introduced the new Mr. X to reporters. Ashe heaped praise upon Wilson, telling the press, "He recognizes the law as it is. He is a public servant and feels no more responsible for an electrocution than the judge and the jury." Although Wilson appeared reticent to talk to reporters, the bespectacled electrician virtually became an overnight celebrity.

Upon returning home, Wilson grabbed his shotgun and headed to Pymatuning Dam. Hunting was his passion, and when he returned from his trip he was met by a throng of newspaper reporters.

"Come in, fellows, I was just stuffing a duck," said Wilson to his visitors. But if they had been expecting the same timid and shy man they had met at the warden's home a few days earlier, they were in for a pleasant surprise. Wilson seemed to revel in his newfound celebrity and talked freely about his job, and his philosophy pertaining to capital punishment. "These fellows may come from good families, and it's just too bad that they get in jams, but the job has to be done," Wilson said to reporters from the Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph, and insisted that the electric chair was the most humane method of imposing the death sentence.

"What the general public doesn't realize is that a person is rendered unconscious by the first shock," he explained. "After that, death comes quickly and is painless. The victims don't suffer."

A Cool and Methodical Killer

Because of Wilson's sudden fame as the state's first full-time executioner, the public clamored for more information about the bookish electrician's personal life. For most citizens, this was the first time they had ever been able to connect a name with the mysterious death-dealer known previously only as Mr. X. They found every detail about his home and work life fascinating, from his living arrangement taking care of his elderly mother at her North Side home at 2621 Ellis Avenue after the death of his father in 1934, to his parenting of two young boys, Robert and Frankie.

The public seemed especially fond of the new executioner after it was reported that he had learned his trade by taking night classes at the Carnegie Institute of Technology while working a day job to support his family. He quickly rose through the ranks of electricians and had worked in New York for several years as a supervisor in an engineering firm. State officials described Wilson as "a poor, deserving electrician" who was selected for the job at Rockview after Warden Ashe had been dissatisfied with the 70 applications he had received for the position of Mr. X.

The public also followed the executions at Rockview Penitentiary closely. After Wilson experienced a little trouble dispatching armed robbers Charles Golden and Walter Tankard to their maker on October 30, the Pittsburgh Press remarked that the prison physician, Dr. Schwartz, slowly shook his head after listening to the heart of Golden. Wilson calmly reapplied the current and gave the condemned man a second shock, and, finally, a third. Wilson also required three contacts to execute Tankard, causing the Press reporter to lament that this was "something that has not happened within the memory of veteran observers", many of whom noted that Robert Elliott could've done the job with only one contact apiece. Nevertheless, observers also noted that Wilson appeared "cool and methodical", operating the switch with one hand while glancing at his watch on the other. This was to become his trademark style.

While Frank Lee Wilson was a hero to some, other viewed him as a villain-- a state-sanctioned killer, who, if history was any indication, would someday crack under the strain of his gruesome job. Dark family secrets began to spill out, such as the fact that his older brother, Walter Boyd, had been arrested in 1924 on a felony count of smuggling whiskey and other contraband into prison for Western Penitentiary inmates while working at the facility as a guard, which resulted in a drunken riot in which two of his fellow guards were slain. Little is known of the mother of his children, but census records show that she was not living at the Wilson home on Ellis Avenue.

A Mysterious Marriage

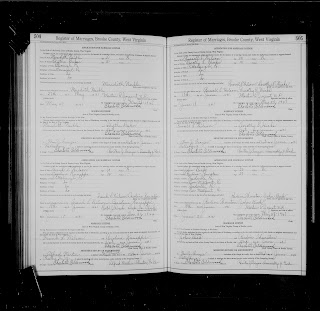

But there was love in the air for Mr. X; on June 21, 1941, Wilson married 35-year-old Caroline Knueppe of Pittsburgh in a secret ceremony in the West Virginia panhandle. There's some mystery involved in this union; the application for the marriage license was filed in Brooke County, but the minister's return of endorsement clearly shows the document was signed by Alfred Martin of Chester, West Virginia, which happens to be in neighboring Hancock County. Strangely, Martin had crossed out the term "minister of the Gospel" which was pre-printed on the marriage record. In other words, it is unclear whether Frank and Caroline were married in Hancock or Brooke county, and whether or not Alfred Martin was really an ordained minister-- there appears to be no other mention of him in Chester church records (and Chester is a small town), and every other minister who completed marriage applications in Brooke County signed their names with the title of Reverend.

|

| Frank and Caroline's marriage license application |

The following year, Wilson was approached by a warden from South Dakota to assist him in designing that state's first electric chair, but wartime shortages of copper wire forced Wilson to scrap his planned trip to Sioux Falls. After the death of his mother, he relocated with his wife to a modest brick house at 160 Crestview Drive in the Pleasant Hill neighborhood of Pittsburgh, where he continued to work by day as an electrical engineer.

There was no shortage of work for Wilson at Rockview, however; Mr. X pulled the switch on dozens of killers over the next few years, which included the likes of John Childers, Michael Musto, Herbert Green, "Big Mike" Bubna, Shellie McKeathen, Frederick Morris, William Kenny Wilson (who had the uncanny coincidence of being sentenced to death by a judge named Wilson and electrocuted by a man named Wilson), William Ramage, Grant Holley, Rufus Keller, and Corrine Sykes, who was the first female in fifteen years to die in Rockview's electric chair.

Scandal Rocks Rockview

By this time, death row inmates and prison officials weren't the only ones who had come to regard Frank Lee Wilson as impassively cool and emotionless. Citing "cruel and barbarous treatment" at the hands of her husband, Caroline Wilson walked out of their Pleasant Hills home in the summer of 1951 and promptly hired an attorney, Charles W. Herald, and sued for a "bed and board" separation. Unlike a divorce, this arrangement would prevent either party from legally remarrying and could result in the family property and assets being divided equally, if a judge saw fit. Frank Wilson called his wife's accusations "bunkum" and immediately gave his side of the story to the press.

According to Frank, on the night of August 16, the Wilsons had finished watching television and Frank had gone to bed when Caroline, upset over some trivial matter, began slamming doors and rattling the blinds in a fashion not in keeping with the lateness of the hour. He ordered her to "cut out the three-ring circus" and come to bed. He admitted that he may have shoved her toward the bed. Caroline went to a neighbor's house and contacted a justice of the peace. In the morning, Frank left for a fishing trip on the Chesapeake Bay and returned five days later. During this time, Mrs. Wilson had gone to St. Francis Hospital for an examination, but doctors told Frank that they had x-rayed Caroline and had failed to find any sign of injury. Frank pointed out that he had been the one who had called the authorities on his wife two years earlier after she had threatened him with a gun, warning him that "I can shoot as straight as you." After this first separation, they had agreed to divide $7000 in savings bonds between themselves.

"I hope she comes back," Frank added, but Caroline was unmoved. She took up residence at an apartment complex on Baywood Street in Mt. Lebanon. The real-life soap opera would play itself out in local papers until its ugly and controversial conclusion in 1953.

By this time, Warden Ashe had stepped down from the helm of Western Penitentiary and Rockview and was replaced by the longtime superintendent, Dr. John W. Claudy, who also a close personal friend of Wilson. After a series of bloody riots rocked both facilities on January 18 of that year, Governor John S. Fine empaneled a commission spearheaded by Jacob L. Devers to investigate the matter. The scathing report of the Devers Committee sent shockwaves across Pennsylvania, with its accusations on unsanitary conditions, rampant "sex perversion", inhumane treatment of prisoners, and its declaration that sweeping changes needed to be made all the way from the top down to the "least custodial officer". The Devers report also blamed guards for allowing liquor, weapons and other contraband to be smuggled into both facilities. Surely these finding must've weighed heavily upon the executioner, whose brother had been charged with the same exact crimes three decades earlier.

Claudy, who was also an ordained Presbyterian minister and had previously served as prison chaplain, fired back with a 17-page retort of his own before resigning on May 2, against the advice of the prison's board of trustees. He was immediately joined by Frank Lee Wilson, who was said to remarked, "If Claudy goes, so do I." He told reporters that both he and Claudy had been contemplating retirement long before the January 18 riots, and that the findings of the Devers Committee had nothing at all to do with his decision. Wilson was credited with 55 executions at the time of his resignation.

"I started to resign three years ago," said Wilson, "but Dr. Claudy was carrying a heavy load. I promised I wouldn't let him down, but that I would leave when he did." The heavy load to which he was referring was the death of Claudy's granddaughter following an operation, and this statement was verified by the disgraced warden.

"My plans to retire are merely coincidental with the present situation," Claudy told reporters. "They have been in the making for some time, prior to any disturbance or investigation at the institution. My retirement is hastened by a personal tragedy in my own family." A few days later, deputy warden William Gaffney resigned his post of twenty years.

A Ruined Man

The fallout from the damning Devers report led to the separation of Western Penitentiary from Rockview in 1953, which, up to that time, had been a "branch" of the Pittsburgh institution. As for Mr. X, he was unscathed by the scandal-- his reputation had already been destroyed by his estranged wife.

The legal proceedings between Frank and Caroline reached a new level of bitterness just days after the prison riots, months before the findings of the Devers Committee had been made public. On January 29, 1953, she testified before Judge Homer S. Brown that she had received no financial support from her husband since their separation two years earlier. She then proceeded to tell Judge Brown that the troubles began soon after their marriage in West Virginia. She claimed that Frank had given her a black eye during an altercation in 1943 and offered a photograph of her injury as proof, and claimed that a few years later things turned physical during a game of bridge.

"He threw his cards in the fireplace," Caroline stated. "As I got up he hit me and knocked me the length of the room." Caroline Wilson then told the judge about an altercation in July of 1948, in which Frank knocked out one her front teeth after she had accidentally stepped on his glasses.

"I bear a scar under my nose to this day," she said. Other incidents, according to Mrs. Wilson, included her husband threatening to break her neck and attempting to run her over with his car. But her most startling accusation was that her husband had once beaten her so badly that it left her face partially paralyzed for six months. It's anyone's guess whether or not Caroline had a flair for melodrama or exaggeration, but Frank didn't seem to have much of an interest in defending his reputation. Instead, he quietly reached a settlement, whereby he agreed to pay his estranged wife $145 a month support.

Jerry Kraemer assumed the position of state executioner in 1954, though Wilson was present at a handful of Kraemer's first executions to offer advice. Much like Robert Elliott, Kraemer's opinion of capital punishment changed and he resigned his position after pulling the switch 19 times in his 8 years on the job.

The last days of Frank Lee Wilson are shrouded in mystery, with some newspaper articles claiming that he became an alcoholic and died impoverished in the county poorhouse a few years later. He never remarried, and neither did Caroline, who passed away on July 11, 1966.

Sources:

Pittsburgh Daily Post, Feb. 14, 1924.

York Daily Record, July 31, 1926.

Hazleton Plain Speaker, Oct. 10, 1939.

Hazleton Standard-Speaker, Oct. 23, 1939.

Reading Times, Oct. 23, 1939.

Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph, Oct. 28, 1939.

Pittsburgh Press, Oct. 30, 1939.

Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph, Oct. 30, 1939.

Pittsburgh Press, June 11, 1942.

Pittsburgh Press, Aug. 24, 1951.

Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Jan. 29, 1953.

Pittsburgh Press, Jan. 30, 1953.

Pittsburgh Press, May 21, 1953.

Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, May 22, 1953.

Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph, June 17, 1953.

Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, June 18, 1953.

Pittsburgh Press, July 24, 1988.

Frank Lee Wilson lived in Confluence, Pennsylvania after moving from Pittsburgh.

ReplyDeleteOn July 18, 1970 one Allen Robert Bowers was shot in the head with a 12 gauge shotgun while on Wilson's property. (1) Charges may have been subsequently brought by police against Wilson, but I could not find further detail than the one mention in an article (2)

Frank Lee Wilson was mentioned in his sister's 1974 (3) and later his brother's 1977 death notices (4) which both ran in the Pittsburgh Press.

In May, 1976, Frank Lee Wilson was involved in a single vehicle crash in the small community of Trent, PA. He suffered minor injuries (5).

In April, 1979, Frank Lee Wilson had his engineering license suspended by the state for lack of a timely renewal. It was indicated that he still was living in Confluence at that time. (6).

The above information demolishes the unsubstantiated 1974 claim by the Philadelphia Inquirer reporter Willard Randall in his expose article about execution history at Rockview Penitentiary that Wilson had already died destitute in a county poor farm (7)

(1) "Pittsburgh Man Shot Near Yough", (1970, July 20). Somerset (Pa) Daily American, p. 1

(2) "Shooting of Man Probed", (1970, July 20). Uniontown (Pa) Evening Standard, p 23.

(3) - Obituary for Lillian Thoman (Frank's sister), (1974, March 21), Pittsburgh Press, p . 40

(4) Obituary for Walter Wilson (Frank's brother); (1977, July 9), Pittsburgh Press, p. 12

(5) "Weekend Heavy for Local Police" (1976, May 10), Somerset (PA) The Daily American, p. 2

(6) "Licenses Suspended" (1979, April 25), Somerset (PA) The Daily American, p 56

(7) "Last Hours of a Condemned Killer"; (1974, June 2), Philadelphia Inquirer, p. 307